A strange thing has been happening at some public architecture talks lately, perhaps you’ve noticed.

Over the course of otherwise hopeful and positive discussions covering amazing new projects from around the globe, at some point, usually toward the end of a talk, conversation turns to the current state of American building and infrastructure. And, it’s safe to say, people are not happy.

Sometimes, the presenter will rip off the bandaid, as Thom Mayne of Morphosis did at a recent Facades+ talk in Los Angeles, when he said, “I hate to be negative, but there’s not much going on in this country architecturally,” before adding, “[But] if you look at architecture around the world, it’s startling…It’s unbelievable, the research [taking place]—I just came back from Shenzhen [China] and I’m looking around [at the skyline] there wondering ‘is there anything left for me to do?’”

Other times, a perplexed-sounding audience member will ask what it seems many in attendance had been pondering privately: “Why can’t we build like this here?”

It’s a debilitating question that really only has one answer. And although, even when speaking bluntly, everyone tries their best to truth-tell without offending, but the writing is right on the projection screen—building big in America simply isn’t what it used to be, and we don’t know what to do about it.

“The United States is falling behind,” architect Moshe Safdie explained to a packed room during a recent keynote talk at Palm Springs Modernism Week when asked why the inventive array of projects he had just presented are mostly located outside the United States.

“Around the world, the competition [for bold infrastructure] doesn’t stop,” he said, half-jokingly, “until you land at Kennedy or LAX.”

To prove his point, Safdie pointed out further that although the Hudson Yards development in New York City is the largest privately-led construction project in the country by square footage, it is easily dwarfed in terms of vision by countless projects around the globe of a similar or larger size.

He’s right. Hudson Yards is a dime a dozen as far as global mega-projects are concerned. Safdie’s own Raffles City development in Chongqing, China, for example, might be roughly two-thirds the size of Hudson Yards, but it is going up in less than one-third the time and is almost entirely designed by a single architecture firm—Safdie Architects—with P&T Group International Ltd. serving as architect of record.

Safdie’s own portfolio of recent work shows that while New York occasionally will build an elevated billionaire citadel, Chongqing, Singapore, and other cities have tasked his office with erecting bold new structures designed for working people and the public at large, all without sacrificing design quality.

Safdie explained that one possible reason why American projects no longer lead the world in terms of size or scale might be due to a “lack of urban initiative,” the type of sustained and calculated political and managerial energy necessary for bringing to life the types of large-scale and lasting projects that have transformed other countries around the world in recent decades. It’s a sentiment echoed by Rem Koolhaas, who, when recently asked about the prevalence of NIMBYism in America, explained, “I think you can divide the world into one part that is eager to change and doesn’t have hesitations about things changing, and another part that is totally nervous about change and actually aspires to a kind of stability.”

Koolhaas added, “As an architect, every one of your efforts is impacted by this. In the end, however, architecture is always controversial because it proposes to make things different than they are.”

Perhaps nowhere is this truer than in the realm of high-speed rail (HSR), where American decision makers across all levels of government have persisted in remaining tethered to auto-centric planning, condemning the nation to antiquated transportation for at least another generation.

A recent article in The New York Times covering the ongoing debacle with California’s tragic HSR project, for example, brings this condition into sharp relief with the following line: “California’s High-Speed Rail Authority…was established 23 years ago. During that time China has built 16,000 miles of high-speed rail.” America has built none.

But America’s last-place finish doesn’t end with rail or with deteriorating airports; it includes city-building, too, as Safdie pointed out.

Much of America is suffering from some form of housing crisis, whether it’s so-called Rust Belt cities struggling to retain residents or coastal cities that can’t figure out how and where to build new housing fast enough. While American cities have doubled-down on onerous building restrictions and lengthy bureaucratic reviews, politically polarized state and federal governments have worked at cross purposes, too, failing to enact bold plans and avoiding future-oriented thinking at almost all costs. The overarching legacy of redlining, racial segregation, and income inequality has placed a stranglehold over American cities, as well, contributing to intense gentrification when development does occur and debilitating displacement when it doesn’t.

Over the last decade, it has become clear that America’s public health, land-use, and transportation policies are all woefully out of whack, and the result is stifling the abilities of a generation of well-trained architects and engineers eager to build a better nation.

Meanwhile, the world’s urbanizing areas have embraced building vertically, have expanded transit of all sorts, and have worked to enact bold planning initiatives that over a generation have remade the face of global urbanism in the name of interconnectedness, density, and place-making.

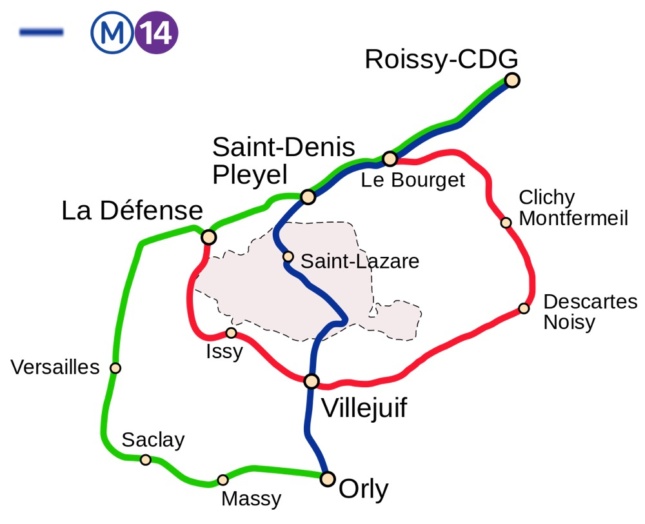

In Europe, for example, France is currently enacting its “Le Grand Paris” plan, a vision that will stitch together the Paris city center with its inner and outer ring suburbs to bring together an urban region of 10 million inhabitants. The plan includes a €30 billion public transit expansion initiative that will create a network of regional transit routes connecting suburbs with one another as well as sizable new investments in social housing, parks, and other equity-minded initiatives.

But it’s not just Europe.

Cairo, Egypt, is building a new $45 billion capital city that, when completed, will become the largest purpose-built capital city by population in the world.

In India, the country’s largest infrastructure project, the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, aims to connect the nation’s political and economic capitals with a 900-mile long conurbation made up of 24 urban “nodes.” The plan aims to urbanize 14 percent of India’s population—180 million people—over the next 30 years and will take $100 billion in investment to realize.

In South America, Argentina’s so-called Belgrano Plan will bring $16 billion in rail expansion to 10 of the country’s neglected northern provinces and will create up to 250,000 new housing units and 1,100 childhood education centers.

Saudi Arabia is building new mega cities from scratch, as are China, Singapore, Nigeria, Mauritius, and countless others.

None of these projects are perfect socially or environmentally-speaking, to be sure, but one thing they do not lack is vision. If it feels like the most impressive work is taking place in other countries, that’s because in many ways, it is, and international architects know perhaps better than anyone else the truth of that reality.

Even more, the hesitation, hedging, and hand-wringing that accompanies talk of the current state of American infrastructure and urban vision indicate that the problem runs deeper than a mere lack of funding or risk-averse clients. Whether it’s California’s flailing HSR project, the nation’s intractable housing crises, or even, the sad, dispirited political discourse surrounding the Green New Deal—a potentially transformative plan that is barely supported by the party that conceived it—it is clear that America has a crisis of vision, a failure of political will, and perhaps most alarmingly, no real interest in solving its own problems.

Look at the Salesforce Transit Center debacle in San Francisco, Elon Musk’s substandard and retrograde transit ideas in Los Angeles and Chicago, and the steady stream of failing bridges and tunnels across the country for further proof.

Even Amazon’s HQ2 extravaganza, a year-long publicity stunt by the world’s richest company that wrung billions in incentives from some of the most desperate cities around the country, rightfully withered on the vine.

What’s going on here?

As Safdie quipped, “We were promised infrastructure!” But the truth is that it’s just not happening in America anymore.