One Manhattan Square, an 800-foot-tall glass tower in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, is at the center of a grassroots battle against displacement. Designed by Adamson Associates, the Extell Development–backed skyscraper threatens to push out throngs of immigrants and longtime local residents who call the area home.

It’s a common story found in the ever-evolving city, but this particular narrative possesses one distinct difference: It’s location. Since much of New York’s luxury residential building boom has focused on expanding Hudson Yards, buffing up Billionaires’ Row, and readying Long Island City for Amazon’s HQ2, the Lower East Side has been somewhat unaffected by such large-scale development.

Until now.

A series of sky-high apartment buildings, starting with the nearly-complete One Manhattan Square (also called Extell Tower), is slated to dot the Lower East Side waterfront enclave known as Two Bridges. Four planned towers are in the works, although One Manhattan square is the only one currently under construction. The surrounding community is predominantly composed of Chinese immigrants and working-class people, a major reason why the city designated the neighborhood a Large-Scale Residential Development (LSRD) area in 1972, which protects and promotes affordable and mixed-income housing for residents.

According to Zishun Ning, leader of the Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side, the proposed high-end projects violate the LSRD, which requires that all new developments secure approval from the City Planning Commission or receive special permits through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process. Ning argued the city’s decision to move forward with the Two Bridges development is therefore illegal, and indicative of discrimination from the mayoral administration.

Not only is it politically fraught, according to Ning, it’s socially irresponsible. The towers are situated within a three-block radius of each other and will sit near NYCHA housing. One will cantilever over an existing senior center and another, One Manhattan Square, will feature a “poor door,” as the coalition calls it, for the building’s affordable housing residents.

Yesterday a slew of protestors gathered at the 80-story tower and marched to City Hall in opposition to the plan. Ning said the day’s event, officially titled the March to Reclaim the City, was the coalition’s latest attempt to get Mayor de Blasio’s attention. “We’re not against development,” Ning said, “we just want some regulation and future development that fits our community.”

Last fall the group submitted an alternative proposal to the commission in which the neighborhood could be rezoned for more appropriate use. They integrated height restrictions on new construction and called for 100 percent affordable housing on public land. Ning said their efforts were ignored, and in early December, the commission approved a special building permit submitted by the developers. The commission said the projects only presented a “minor modification” to Two Bridges’ zoning law and that a full Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process would not be required.

“It’s evident that racism plays into the city’s zoning policies,” said Ning. “They rezone communities of colors for the interests of developers. We call out the city’s illegal approval, along with Mayor de Blasio’s collusion with developers to approve these towers and deny our plan that came out of a democratic process. We want to reclaim our democracy and control as a community.”

History has seen many local working groups stand up against giant developers and influential politicians, but, according to Ning, there needs to be more support from area architects to help such groups envision a bigger, more inclusive picture for their neighborhoods.

A new collective of aspiring architects and non-architects interested in the field, citygroup, wants to do just that. The organization aims to become a young social and political voice for the architecture industry. Members gather periodically for informal debates on serious topics like the need for affordable housing in New York, the nature of architectural expertise, and architects’ tricky relationship with real estate developers.

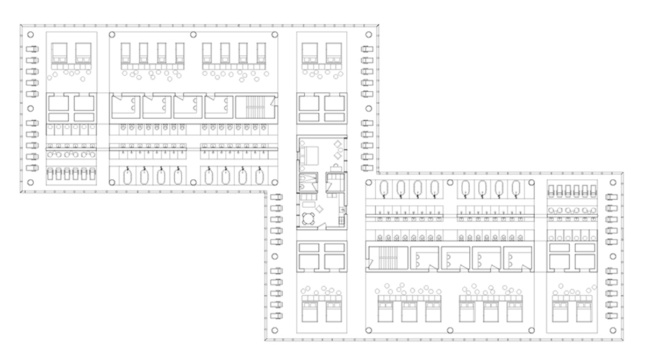

The group’s inaugural exhibition, set up inside its new space on the Lower East Side, details various visions of One Manhattan Square that imagine a more useful development for the local community. “We wanted to rethink the Extell Tower as something that isn’t as foreign to this neighborhood as it is now,” said Michael Robinson Cohen of citygroup. “It’s built on a plinth and houses mostly luxury apartments. We asked ourselves, How could we recreate the tower for different uses or for a diverse group of inhabitants?”

The exhibition centers on a series of 21 drawings done by different citygroup members. These individual visions, expressed within the confines of the building’s plan, feature different ways to reuse the tower’s 1.2 million square feet of space. Some pictured it as pure parkland, others cut it up into a grid of 3-meter-by-3-meter apartments. One strips away the idea that a housing complex must cater to the traditional single-family home by creating personally-designed apartments outfitted for everyone from single moms to yoga teachers, a Russian oligarch, a cat lady, and even a family of five.

Thinking critically about megaprojects like One Manhattan Square, according to Robinson Cohen, allows architects to investigate the best ways for new developments to improve a community, instead of displacing residents and stripping away the character of a neighborhood.

“Much like the coalition, we’re for challenging the tower, but are not against development in general,” he said. “Obviously, as architects, we want to build and it’s clear the city needs more housing, but to us it’s important to think about the people these developments serve.”

To Ning, the architect’s mission isn’t far from that of the Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side. He says the two parties can work together to imagine developments that engage with local residents rather than taking away access to light and air.

“We actually encourage architects to put their creativity into building things that benefit the community,” Ning said. “But in order for that to happen, we first need to fight the city.”

A new lawsuit against the City was just brought on by the Lower East Side Organized Neighbors in opposition to the development. The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) is slated to support with future litigation efforts. Until then, the City is still contending with another lawsuit calling for the towers to go through the ULURP process, initiated by City Council Speaker Corey Johnson last month.

“These towers are just one piece of a bigger picture,” noted Ning. “If 3,000 units are added to the neighborhood, the demographics will change and the land value will rise. Harassment and eviction will escalate. This is happening all over New York City. It’s segregation, and it’s very visual.”

Walk-throughs of citygroup’s exhibition are available upon request through early February at 104b Forsyth Street. Email group@citygroup.nyc for hours.