Most architecture students study design precedents or build upon knowledge gained in history courses, but one mid-century educator repeatedly told young minds instead:

Do not try to remember.

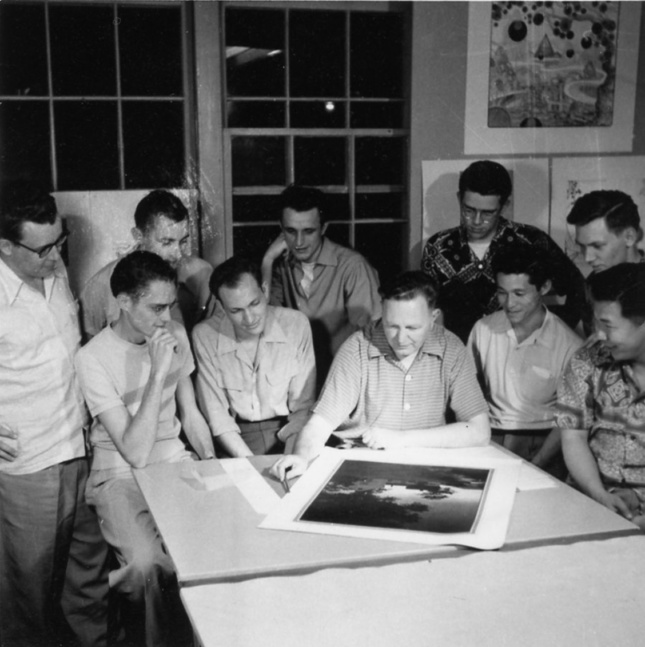

Bruce Goff, a self-trained architect and long-time mentee of Frank Lloyd Wright, instilled this idea in his students at the University of Oklahoma (OU) during his tenure as chairman there from 1947 to 1955. Instead of copying the popular Beaux Arts and Bauhaus styles of the recent past, Goff wanted architects in training to express their own creativity and views of the world through designs that avoided architectural stereotypes and instead presented a radical future. This era of educational exploration and disruption became known as the American School of architecture.

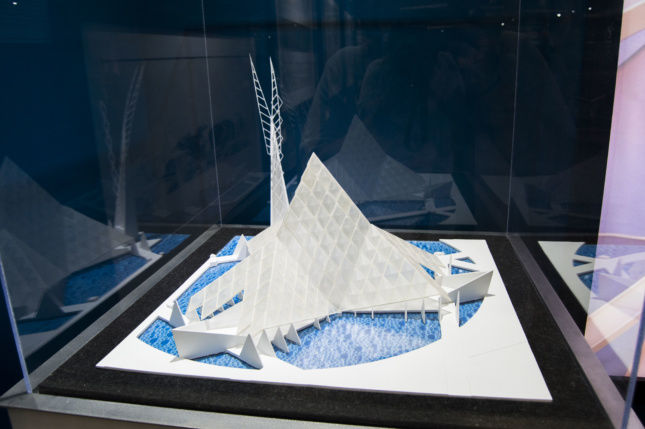

Historian and OU Visiting Associate Professor Dr. Luca Guido is the curator behind the exhibition, Renegades: Bruce Goff and the American School of Architecture at Bizzell. Now on view in OU’s Bizzell Memorial Library, it details the widespread influence of Goff’s personal teaching style and the program he built, which attracted students to the American Midwest from as far as Japan and South America. The exhibit features large-scale drawings by alumni, as well as uncovered models and writings from Goff’s students and colleagues like Herb Greene, Elizabeth Bauer Mock, Bart Prince, Mendel Glickman, and Jim Gardner, and Bob Bowlby, among others.

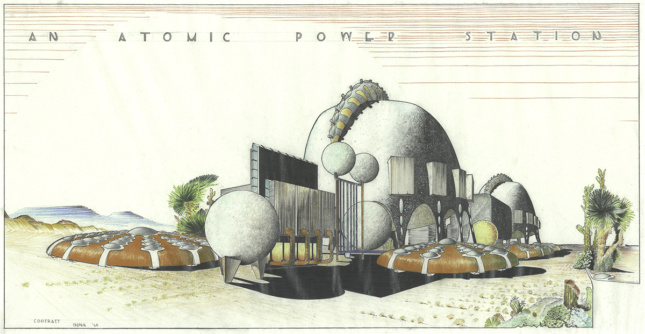

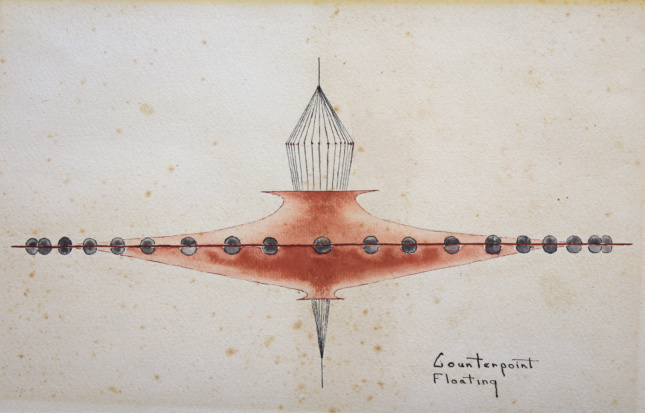

Built from the school’s expansive American School archives, the show unveils former students’ work that’s been so pristinely preserved and restored, it all looks like it was completed yesterday. Goff, who seemed to have encouraged serious attention to presentation, penmanship, and shading, left behind what Guido considers a “gold mine” of materials. Every framed assignment on view is a piece of art in and of itself—a testament to the architectural educator’s guidance.

“Bruce Goff introduced a new architectural pedagogy,” Guido said, “and the School of Architecture at OU endeavored to develop the creative skills of the students as individuals rather than followers of any particular trend. The drawings represent the evidence of an extraordinary and, at the same time, little known page of the history of American contemporary architecture.”

That history is one that OU is now trying more heavily to build upon. As one of just two architecture schools in Oklahoma, OU lures students from across the state, nearby Texas, and around the globe to the small town of Norman. It was considered a world-class institution during Goff’s years and still seeks to live up to that legacy today. Since becoming head of the school three years ago, Dean Hans E. Butzer has worked to re-elevate its status.

“Our discussions over the past few years prove a symmetry between those defining aspects of the American School and the overarching strategic priorities of the Christopher C. Gibbs College of Architecture,” he said. “The work of the American School of the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s may be described as contextual, resourceful, and experimental. Today, we have set the goal of graduating entrepreneurial students who design resilient cities, towns, and landscapes through the lens of social equity and environmental sustainability.”

This idea is evident in the success of last year’s graduating class. As of fall 2018, one hundred percent of architecture students secured a full-time position within six months of graduation, according to Butzer. Only two, the faculty jokes, didn’t get hired. They instead went on to begin master’s degrees at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. When asked why OU graduates are so attractive to firms across the country, Butzer noted the work ethic and creative problem-solving skills they learned as students.

Teaching students to speak up, stand out, and work hard can be traced back to Goff’s presence at the school and his own career as an eccentric architect who always put the client first and aimed to “go the extra mile,” according to Guido. His modus operandi was to first connect deeply with the client, ensuring the end result was strictly their vision. His objective was to never design a building he personally wanted to live in.

Some of Goff’s most famous structures, the Ledbetter House in Norman, the ill-fated Bavinger House that was demolished in 2016, as well as the Bachman House in Chicago, took on forms reminiscent of Wright’s residential work—low-lying residential homes with surprisingly large interiors, cantilevered carports, and large windows—but they all displayed a curious amount of flamboyancy that was signature to Goff himself. The architecture of his early years, such as the historic Tulsa Club and the Art Deco-designed Boston Avenue Methodist Church, are celebrated landmarks in Tulsa and reveal Goff’s visual personality. Goff was also a champion of sustainable and site-specific construction; he often utilized local materials for his projects. Fittingly, Goff rejected the idea of having a personal style of architecture.

Some of Goff’s mid-century work and the sketches of his students from this time seem to be inspired by Atomic Age tropes. Viewing them now, they’re so futuristic they probably seemed structurally unbuildable at the time, but the geometries that came out of the American School were forward-thinking and technically-advanced. During Goff’s leadership, architectural courses fell within OU’s College of Engineering where students were taught how to complete construction drawings and to specify materials. But in Goff’s classes, it was all about creativity.

“Bruce Goff didn’t believe in critiques,” said Guido. “He wanted them completely free to propose what they wanted. The assignments were structured around abstract themes that allowed the students to express themselves in the best possible way because for Goff, there would be no little Corbusier’s, no little Mies’s, and even no little Goff’s. He didn’t want his students to become followers of someone. He wanted them to abandon all memory of what came before them.”

Renegades: Bruce Goff and the American School of Architecture at Bizzell is on view through July 29 and will turn into a comprehensive traveling exhibition this year with a stop at Texas A&M University in the fall. The OU Libraries also has plans to secure the preservation of the archives by making them part of the school’s Western History Collection and digitizing select images for online research.