Although architects design new buildings for well-endowed nonprofits all the time, it is somewhat uncommon for firms known for high design to take on super-low-budget commissions. But Inaba Williams was up for the challenge. For a new preschool in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, the Inaba Williams team drew out the quirks of an awkward, column-filled interior to deliver a luminous space that supports the school’s commitment to immersion in Japanese language and culture.

The Brooklyn-based firm connected with Aozora Gakuen after the school leased the space, which had sat vacant for two years despite its location in a desirable neighborhood. Unlike most chronically empty New York commercial properties, the rent wasn’t too high for prospective lessees—the space was just too weird. The second floor, where the school is located, doubles as the structural transfer level between the apartment tower above and offices and a parking garage below. In plan, the structural columns look like confetti left over from a manic crafting session.

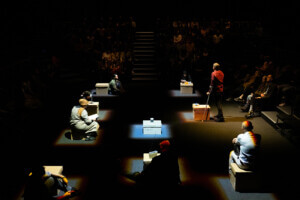

To reconcile the column array with the client’s needs, the team highlighted the irregularities of the 3,500-square-foot space while harmonizing the circulation pattern across three classrooms, a bathroom, and a shared kitchen. Inaba Williams founding principal Jeffrey Inaba opted to move the classrooms to the perimeter and organize an interior pickup and drop-off area (called the Aozora Room, “blue sky” room in Japanese). Surrounded by glass panels that pull light in from the street-front classrooms, that area is the heart of the school as well as a transitional space from the outside world into the classroom. Along with cubbies (getabako), it’s delineated by a raised wood floor that physically separates the shoes-on portion of the school from the classrooms, which, in accordance with Japanese custom, are shoes-off.

Typically, architects work to mask irregular features, but in the Aozora Room, they turned what Inaba deemed “the craziest part of the structure” into a defining feature. Making use of what he called “an aspirational Marcel Duchamp door,” a reference to the French artist’s Door: 11, Rue Larrey, the design now has one door leading from the bathroom to the classroom and the other leading from the bathroom to the Aozora Room’s threshold area. All the doors can be opened for seamless circulation or closed for activity separation.

To save money, the firm installed standard fixtures and “very, very economical” wood floor and tiling. While Inaba declined to go on the record with the budget, he did say the project cost far less than a typical New York institutional interior—without sacrificing design quality. Consequently, “there’s programmatic variability with very simple elements,” he said.

Beyond design, the experience made the firm excited to work with other mission-driven clients. “There are many organizations where the physical space is critical to what [the client] does, but they don’t have the means to afford an architect or think about design,” Inaba said. “To be able to work with a group and make a space that aligned with their teaching philosophy was really important.”