When reflecting on the recent art and architecture scene of Los Angeles, a familiar cadre of names will typically come to mind; Ed Ruscha, Frank Gehry, John Baldessari, and Thom Mayne, to name a few. But beyond the figures that have famously channeled the city’s flair for the dramatic into their creative work, there is at least one artist that has made the spotlight his artistic subject while avoiding it for himself altogether.

William Leavitt, now 78, has been quietly producing art about the uniquely modern spectacle of Los Angeles and its built environment since the late 1960s. Leavitt was stunned by the scale of Los Angeles and the hold the movie industry had on the city when he arrived in 1965. Part of a generation that reacted against the plain functionality of modernism in favor of a burgeoning commercial language designed for mass appeal, Leavitt continues to produce illustrations and sculptures which pay special attention to the architecture and interior design aesthetic present in the soap operas, furniture showrooms and suburban basements of the time. Like Ruscha and Gehry, Leavitt was an out-of-towner fascinated by the hastily constructed buildings that popped up around Los Angeles during the 1950s and 60s.

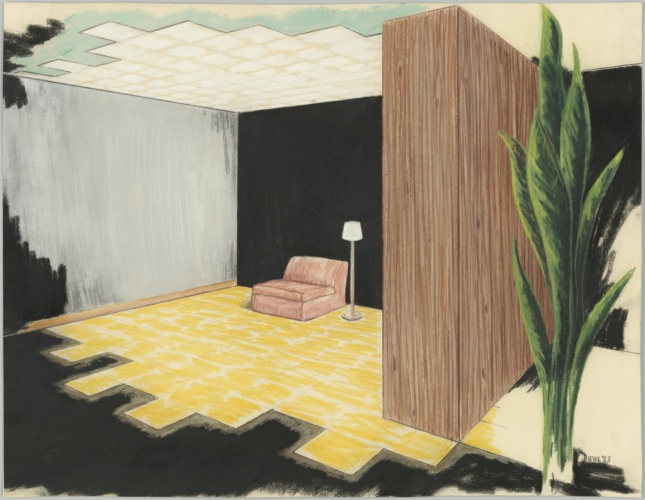

But that would be selling Leavitt’s inspirations short. The artist skillfully conflated the kitsch and thinly veiled constructions of mid-century America with the sparse beauty of stage set design employed in so many of Hollywood’s movie studios and independent theatres. In 1988, he wrote about the first time he visited the backlot of a movie studio: “I loved the deception of going up to one of those perfect houses and opening the door and seeing that there was nothing but canvas and 2x4s holding it up. I thought that was spectacular: all the bricks were made of composition board.” The unique balance of image and reality on display throughout the city’s built environment is Leavitt’s primary source of inspiration.

While the minimal stage sets of movies and plays are designed to appear more complete to their audiences fixed in place, Leavitt invites his audience to study his sets up close and in the round. As Ann Goldstein described his work, it “tak[es] into account the theatrical potential of the ordinary” while “considering the significance of every detail – location, lighting, atmosphere, props, and sound – and, like a set designer, he assembles a scene where every element plays a role.”

One of his most well-known installations, California Patio (1972) is a sculpture depicting an entire setting: a freestanding sliding glass door between blue curtains framing a truncated woodchip garden. The materials of the entire piece might well have been purchased at a local hardware store, yet they become more than the sum of their parts; the 2x4s holding up the structure are more cleanly nailed and the sandbags more delicately placed than what is typically hidden from the screen or the stage. Leavitt’s illustrations, meanwhile, are reminiscent of those used by art directors to describe a stage set to a production crew. In Electric Chair (Interior) (1983), for example, efficiently depicts a sparse basement in which function and utility might be easily be confused for one another.