The weekend before I left for Venice, I caught the eye of a guy on the street near my apartment in Brooklyn. After we passed each other, we turned around to check each other out. It wasn’t until I got home minutes later, and logged onto one of my geo-social “dating” apps, that I received a confirmation of our interaction: “What were you looking at, boy?” typed the same guy on his phone, now 700 feet away from my house. This encounter collapses two different modes of cruising, the historically perambulatory practice of searching for sexual encounters, which, in the digital age, is shifting more and more to mobile devices. The variant practices and habits of cruising form the subject of the Cruising Pavilion, an off-site group exhibition curated by Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, and Charles Teyssou held during the vernissage of the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale.

Cruising is a covert act that takes place in plain sight. Cues like locked eyes, a turnaround glance, winks, gropes, all signify consent to approach one another. Its signals formed in reaction to bourgeois fears that homosexuals openly forging social connections would upend normative gender relations and, thus the reproductive order. Public restrooms and parks, historically and to this day, are examples of cruising sites: arenas charged with intrigue and hormones. Cruising Pavilion’s curators contend, however, that the parameters of these spaces are evolving due to the advent of apps like Grindr, which use mobile devices to map sexual partners by proximity. At the same time, cities like Berlin have become destinations for sex tourism where clubs and bars recreate the cruising experience in “dark rooms” or bath houses designed with labyrinths and other programmatic devices intended to provoke drifting, encounter, and niches for physical activity. Frequent cruisers shape their physical environment to encourage interaction and to evade persecution. In this way, the story of cruising space is one of persistence, something that the works in the show touch on through the artists’ and architects’ range of interpretation and representation.

The Cruising Pavilion curators designed their exhibition space as a dark room to sexually frame the works on display–a tactic that is sometimes successful, but in others, doesn’t facilitate more erotically nuanced reads of conventionally presented works, especially in absence of wall text. But to over-explain and force a singular narrative would hush the pluralistic modes of sexual communication that this exhibition celebrates. It’s a jolting counterpoint to the official Biennale program, curated by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, whose chosen theme, Freespace, came with a manifesto that omits sex altogether.

The Cruising Pavilion is located in Giudecca, a southwestern spit of land known for Il Redentore, Palladio’s 16th-century Catholic church. Some 100 yards away is a less well-known site: the Garden of Eden, named after Frederic Eden, an Englishman who founded it in 1884. By the early 1900s, it had become Venice’s premier cruising grounds, frequented by the likes of Jean Genet. It’s now in private hands and serves as a progenitor to the Cruising Pavilion, located along the same shoreline in a double-height warehouse.

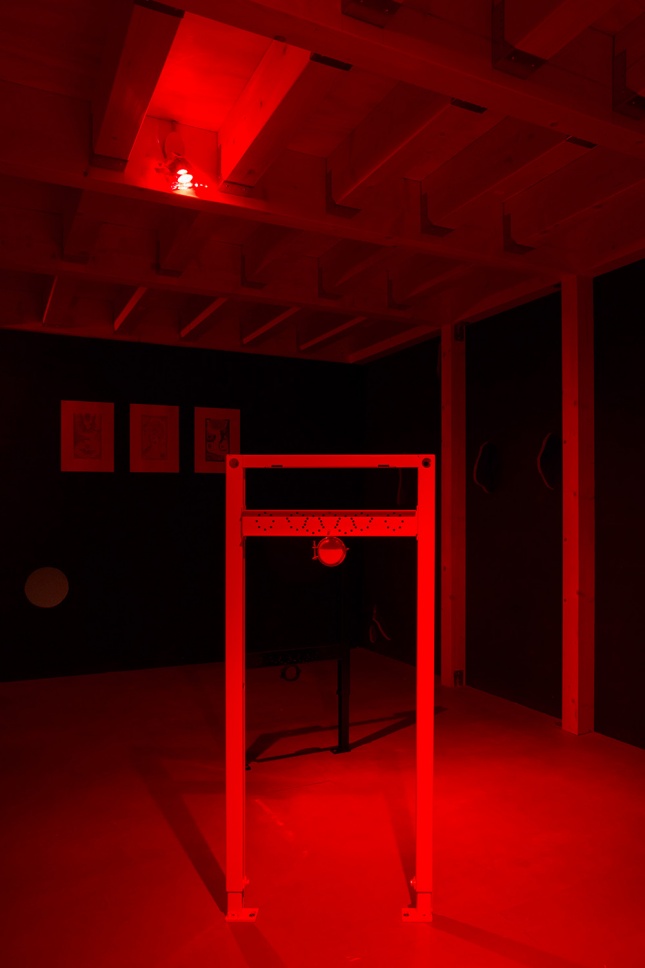

It takes a while for your eyes to adjust when you walk into the space from the unsympathetic Venetian sun: it’s pitch black—save for low-lit red light bulbs, a nod to the lighting design often used in dark rooms. The exhibition opens with a wheat-pasted sign reproduced from the defunct New York BDSM club Mineshaft, open from the mid ‘70s to ‘80s. This dress code was posted on the club’s door alerting patrons to the rules to follow when inside: No cologne, no suits, no ties, and no dress pants, among other maxims. Even the Cruising Pavilion’s original font is derived from scrawls in cedar planks in the West Side Club, a former New York sauna, a gentle nod to past sites of cruising.

The curators made full use of the leftover Icelandic pavilion from a past biennale. Luckily, it fits with their theme. Two giant towers – each two stories and made from standard issue lumber – rise from floor to ceiling. Narrow stairs take viewers up and down different platforms where work is on display. The tight turning radius to transfer from stair to platform reminded me of one of the devices used in dark room labyrinths to generate encounter between patrons. In one such instance, I was confronted by Ian Wooldridge’s readymade sculptures. Square, tubular brackets made mostly of steel rise from the floor like little automatons. They’re braces used to anchor urinals in drywall, but formally, and under the glow of the red light, they read like sex dungeon infrastructure. Each is tricked out with a cross-brace to support a suspended metal ring used to guide pipe conduit. Located waist high, the rings suggest other potential functions. Speaking of holes, Andreas Angelikdakis presents what could be considered an IKEA of dark room design. His sculpture Cruising Labyrinth, is a sheet of ¾” plywood painted black with a simple glory-hole cut out. Takeaway instruction sheets advertise “Every hole has a goal!” so one can make and install their own dark room configurations.

Sex is more difficult to read in works that, at first, seem like pin-ups of simple architectural plans. Etienne Descloux’s drawings, DR01 – DR07, could be mistaken for banal axonometric studies of small pavilions, but he drew these dark room studies as portraits of his friends with whom he collaborated–a gesture that renders the client-architect relationship more intimate and erotic. Another axonometric diagram for a speculative bathhouse to accommodate gender-neutral patrons called S H U Í, accompanies a video used to pitch it to investors. The video subverts the derivative hetero-normative narrative common in advertising for luxury condos, in which straight, white couples gaze out from their new 40th-floor balcony at the city below. S H U Í Bathhouse User 1: Ylang Ylang, by Jon Wang and Sean Roland, instead, presents a gender non-specific Geisha wandering a city at night and into/out of staged wellness environments.

It’s a bit of a myth that Grindr and other dating apps are the first technologically disruptive forces for cruising. Emergent technologies have been creatively co-opted for sexual functions for years. These “hacks” and innovations are evident in the show, if not explicitly stated. A vintage French Minitel machine is installed in Cruising Pavilion’s entry in an incoherent timeline of cruising communications. France’s telephone modem-driven computer device launched in the 1980s was the site of gay chat rooms and two-way communication. Diller Scofidio + Renfro offer a conceptual predecessor to GPS-driven cruising in their Blur & Blush book printed to document their Blur building, a pavilion in the 2002 Swiss EXPO cloaked in a mass of fog. The “Blush” portion of the project was never realized, but the architects proposed that visitors wear coats outfitted with electronic lighting and vibrating sensors that responded, algorithmically, to the proximity of others who had given similar answers to a questionnaire. The architects thus engineer connection between strangers in an obscured environment not unlike cruising grounds. Andrés Jaque’s Intimate Strangers documentary picks up the torch and traces the rise of Grindr from its early days in 2009 as “Near Buddy Finder” to its present platform where users have splintered into hyper-specific “tribes” of interest and identity in an app now crowded with advertising. Visitors can watch it on a laptop on an inflatable mattress, one more nod to the raw interior spaces of dark rooms. Nearby, Prem Sahib and Mark Blower document similar spaces in a series of photographs of Chariots, a London gay bathhouse that was closed and demolished to make way for a 30-storey luxury hotel, a common tale in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods like the city’s newly tony Shoreditch neighborhood.

It turns out that both the digital space of Grindr and the urban spaces of historically queer neighborhoods are both becoming highly commercialized, perhaps at the expense of a community who can no longer afford, but will always find, its freespace. Aestheticizing the cruising experience, as the curators have done with their dark room-inspired installation, risks a similar commodification. But Cruising Pavilion’s mirage-like appearance at this year’s Biennale would have had less public visibility under white fluorescent lights, and its presence filled a void at the official exhibition that, surprisingly, lacked explorations of queer space. Where the project drifts next is unclear, but let’s hope it brings more people into the dark.