Faced with summer temperatures that regularly shoot above 110 degrees Fahrenheit, the city of Abu Dhabi tasked designers with devising long-term strategies for rendering outdoor public spaces more comfortable for human users. Kishore Varanasi, a principal and director of urban design at the Boston– and Abu Dhabi-based design firm CBT Architects, is one of those designers. In a conversation with AN, Varanasi expanded on many of the concepts implemented by CBT Architects across various spaces across Abu Dhabi, and how similar strategies might apply to increasingly hot cities well beyond the Arabian Peninsula, including in the United States.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Summer 2021 was the hottest summer on record in the contiguous U.S. California, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah all broke average temperature records for June through August, while another 21 states registered summers that ranked within the top five hottest in recorded history. An unprecedented heatwave that broiled parts of the Pacific Northwest in late June has been linked to hundreds of deaths in Washington and Oregon, pointing towards a future in which dangerously high temperatures impact regions not yet accustomed to—or equipped for—unbearable summer heat.

As has been well-documented in sociological studies and the news media, there is obvious unevenness in the ways heat affects neighborhoods of disparate racial compositions and income levels. While these inequities are certainly present in the domestic sphere, most notably in the costliness of personal air conditioners, Varanasi pointed out that they are also rampant in public space: “In lower-income communities, fewer people can just jump in an air-conditioned car and be on their way. They’re often walking to bus stops and waiting there.”

Lower-income, racially segregated neighborhoods in cities across the United States usually lack the greenery, shading devices, and distance from major thoroughfares that can help lower average temperatures, contributing to a phenomenon known by environmental scientists as the urban heat island effect. High concentrations of pavement, as well as the presence of building envelopes and other surfaces that can absorb and re-radiate heat, increases cooling-related energy costs during summer months. As climate change pushes temperatures across the continent even higher, the most underserved urban communities are likely to bear the brunt of the human toll.

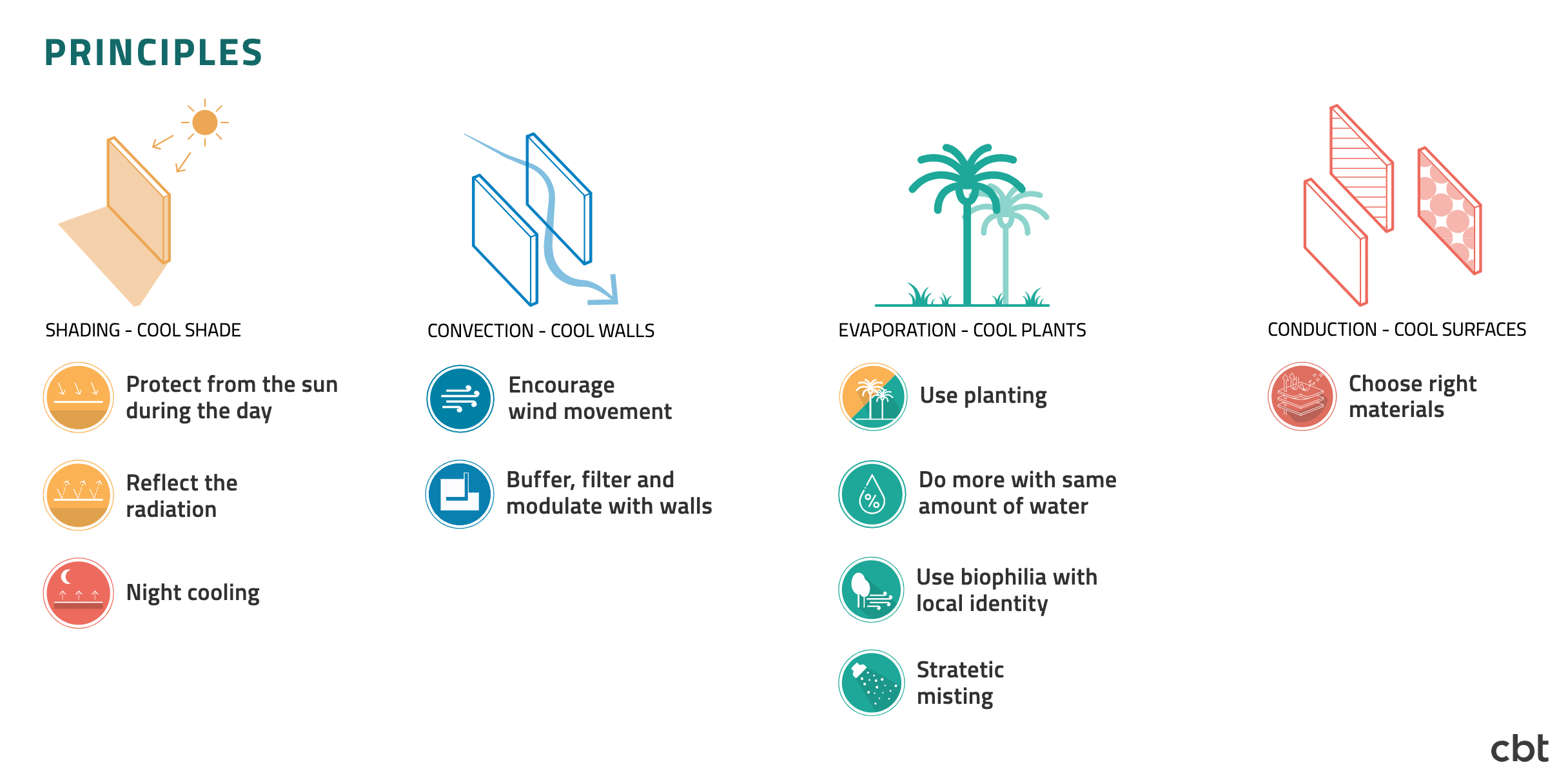

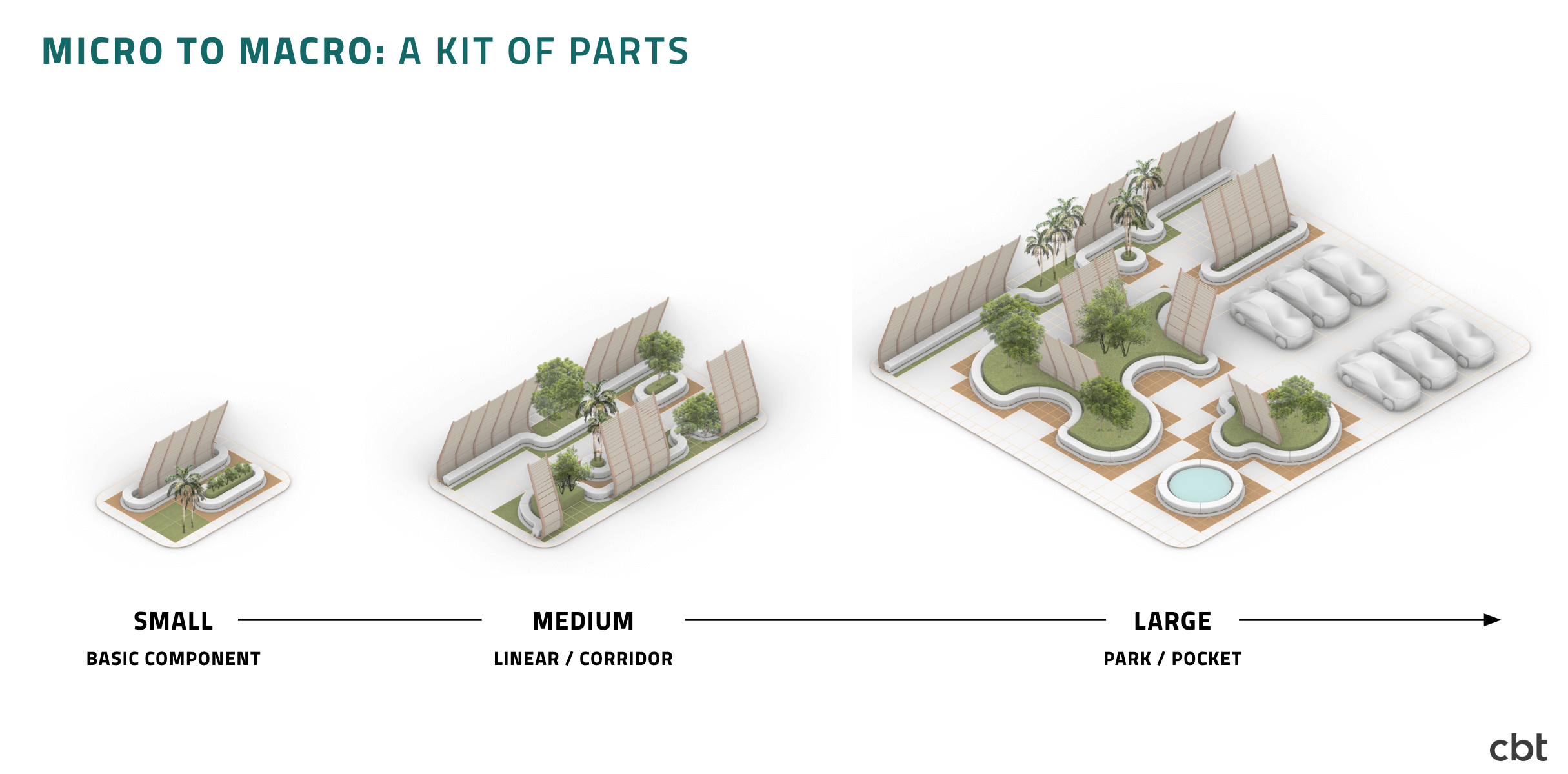

In order to respond adequately to the staggering challenges ahead, Varanasi underscored the need to consider all cooling elements on the street as interdependent components of a system, rather than as individually effective devices. Active systems like misting, for instance, are far less potent when deployed in highly exposed spaces than when used in shaded environments. Similarly, a body of water placed in an open space with direct sunlight usually raises the temperature of the air, while a water feature in the shade can help cool it down further. The architects of buildings that abut the sidewalk can also play a role. Reducing the amount of glazing on a building’s exterior in favor of more solid materials can lower both internal cooling loads and the amount of heat that is reflected back onto the street at ground level.

Layering heat resilience systems is easiest when building from the ground up, such as in Masdar City, a planned sustainable city and technology hub in Abu Dhabi. “Masdar was a tabula rasa,” Varanasi noted, “and we were able to channelize winds, block direct sunlight, and orient buildings properly from the beginning.” But most cities today are not built from scratch, and retrofitting existing spaces can prove particularly difficult. In older neighborhoods and more arid climates, tree planting may not be tenable due to space constraints, lack of natural irrigation, or an overabundance of subterranean infrastructural elements. Complex as it may be, Varanasi suggested, determining how to improve comfort conditions in public spaces where the designer has little or no control over the surrounding architecture or automobile traffic is a worthwhile pursuit.

In three case study projects executed as part of the Abu Dhabi Climate Resilience Initiative, CBT Architects tested various outdoor cooling methods for a high-density area, a low-density area, and an intersection. Varanasi and his team carefully considered shifting conditions over the course of a single day, prioritizing shade for the “shoulder hours” when more people are typically on the street.

CBT modeled one of its interventions, a pocket park, off of the sikka, a traditional alleyway or passage indigenous to parts of the Arabian Peninsula. The orientation of the sikka helps funnel winds into the occupied public space, an effect that, when combined with elements to block the desert’s powerful sunlight, can reduce temperatures substantially. The firm also employed cantilevered, manipulable shade structures to block the radiating heat from an adjacent, heavily trafficked road. The verticality of the devices shifts based on their position within the park or intersection, while benches below provide more temperate spaces to wait for a bus or simply rest.

Some of the ideas implemented by Varanasi and his partners touch on the more psychological dimensions of environmental cooling. Planting greenery, in particular, is multifaceted in its potential climactic benefits. In addition to cycling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and cooling surrounding air by releasing water vapor, plants and trees can induce a less tangible sense of coolness among a space’s users. Even the simple sight of flora, Varanasi argues, can make a space feel cooler to the average human.

CBT insists that such ideas, whether age-old approaches or new innovations, can be deployed worldwide to “offer a new paradigm for public space design for all places that face urban heat issues.” Such moves will only become more relevant and pressing as climate change progresses and temperatures rise across the North American built environment. CBT’s architects and urban designers have already experimented with some cooling devices in their Cambridge Crossing master plan in Massachusetts. Stretching between the municipalities of Cambridge, Somerville, and Boston, the plan incorporates numerous trees and green spaces to help mitigate summer heat in the surrounding area. One of the project’s centerpieces is the Shed, a gabled, partially open-air canopy structure designed by Prellwitz Chilinski Associates that will provide shade and help direct breezes through heavily trafficked public spaces during the summer months.

For northern cities like Boston, though, colder winter temperatures add another layer of complexity to design-based cooling strategies. The logic of passive temperature control systems flips on its head between autumn and spring, when maximal sunlight and less wind are preferable conditions. “Fixed structures won’t always work,” Varanasi said, “So walls might need to move and shading devices might need to move. These are things, of course, that trees already do naturally by shedding their leaves, so maybe there’s a need for a sort of biomimicry there.”

No matter the level of flexibility applied to heat mitigation infrastructure in U.S. urban spaces, it is certain that holistic approaches hold more promise than one-off interventions. Improving street conditions for pedestrians and cyclists, bolstering public transit, introducing plant life, and using appropriate surface materials on sidewalks and buildings are proven methods for ameliorating the effects of the urban heat island phenomenon—ones that designers and planners can help implement across the public realm.

In periods of uncomfortably high heat, Varanasi pointed out that carefully crafted public spaces can offer a more vibrant and ubiquitous alternative to the air-conditioned cooling centers on which cities today heavily depend. As U.S. states continue to shatter heat records, mitigation efforts in public spaces will not just be a matter of day-to-day comfort, but possibly one of survival.