Spatial Infrastructure | José Aragüez | Actar | €35

Featuring a subtle tribute to Fumihiko Maki’s “group form” on the hardcover, Spatial Infrastructure is an eight-essay volume addressing some of the timeless questions shaping the grounds of architecture. Published by Actar, the book reads as a window into an extended intellectual effort by its author—practicing architect, educator, and researcher José Aragüez—who has spent the past 15 years undertaking the difficult task of constructing a theory of architecture through a series of new categories, the most salient of which is announced in the book title. This enterprise responds to a two-fold objective. There is, on the one hand, the aim to claim the specificity—though importantly, not autonomy—of architectural thinking as a form of knowledge that can engage other disciplines without losing its identity. On the other, there is an effort to advance an ambitious conceptual framework: that around the notion of “spatial infrastructure.” Functioning as an analytical tool, spatial infrastructure acts as a critical lens through which to view existing projects, pushing theorists to question their assumed perspectives on the past and present of architecture. Yet it is also applicable to design since it can be mobilized as a heuristic device which encourages architects to reflect upon the very essence of their spatial decisions, and eventually, to explore novel alternatives to dominant models.

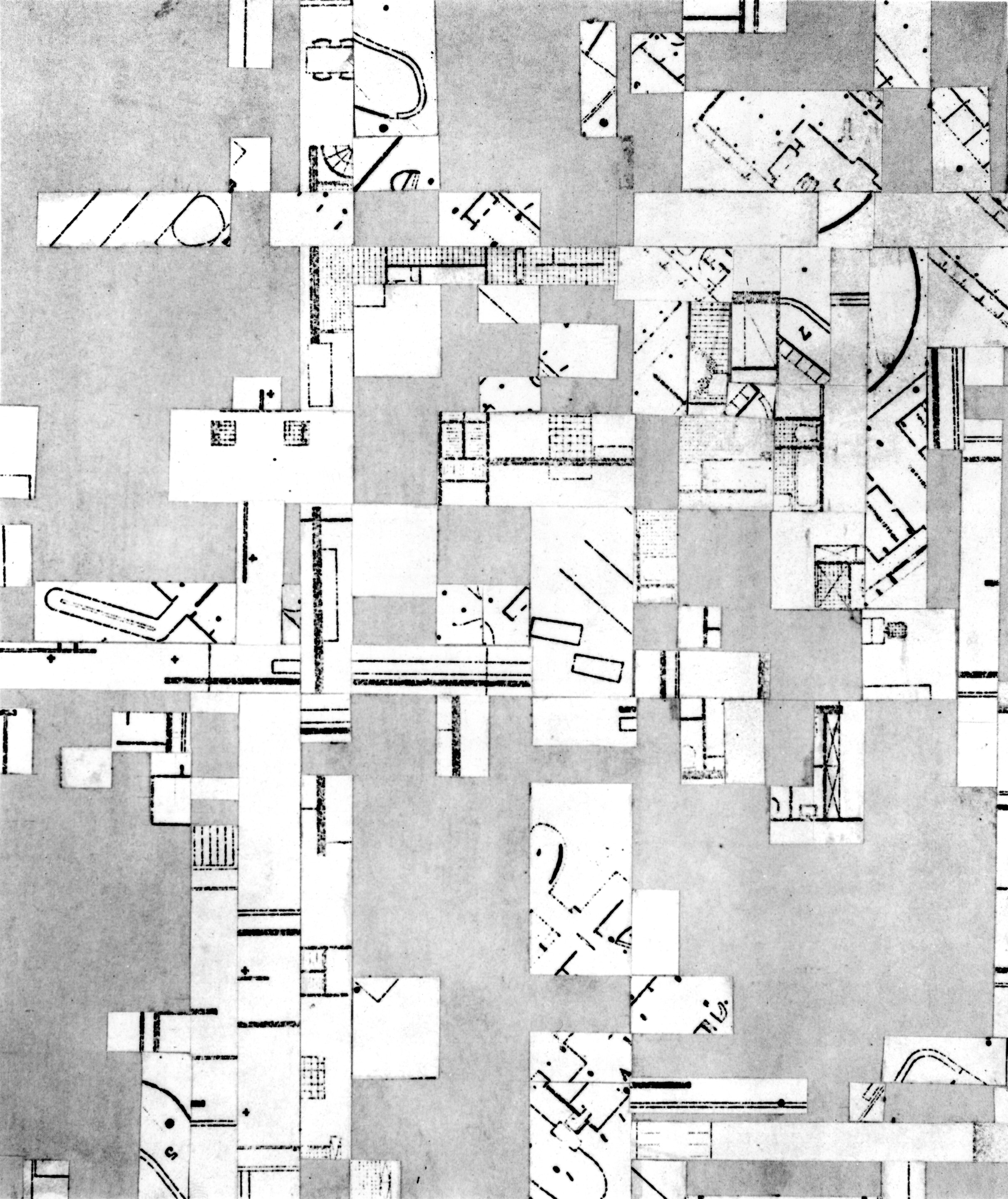

The expression “spatial infrastructure” sounds far too obvious to have never been used before, but this seems in fact its first theorization. The concept refers to a basic component of buildings: the three-dimensional set of elements that provide a primary articulation of space, thereby generating a first series of programmed regions, prior to partitions, and defining a building’s internal identity. Again, a seemingly simple idea, yet one with far-reaching implications. Understanding the book as an ongoing intellectual process makes evident the struggle behind the final choice of the term “infrastructure.” It does not appear until the penultimate chapter, when its theoretical manifesto takes shape. The idea has, however, already seen the light much earlier, traceable back to previous chapters—especially “Toward a Critique of ‘The Organic,” “Critical Imageability,” and “Sponge Territory.” Albeit in embryonic form, the concept reemerges constantly under the guise of assorted variants such as spatial organization, disposition (as opposed to composition), configuration, articulation, and arrangement.

The use of the word “infrastructure” is meaningful for various reasons. First, it does not sound too hackneyed a term when meant to operate within the confines of the building scale, as it is the case here. Second, most importantly, it alludes to the possibility of there being something below and before anything else—a sort of primal skeleton ready to absorb and adapt to whatever is grafted onto it over time. That skeleton or material ensemble can be load-bearing, but not exclusively—a subtle yet crucial distinction that steers discussions into as-yet unexplored avenues relative to related constructs such as Kenneth Frampton’s tectonics or Karl Botticher’s Kernform. The ultimate purpose of devoting so much energy to the precise definition of “spatial infrastructure” is, in words of the author, to prove “the correspondence between turning the question of spatial organization into a primary realm of experimentation and innovation, and the possibility of a building embodying a significant contribution to the history of architecture.”

Discussing spatial organization is not a fashionable move for architects today. It risks sounding too disciplinary for our transdisciplinary concerns; too abstract for our hands-on and sensible approach to the world; and surely too modernist for the 21st century. Yet this apparent out-of-datedness is precisely what makes the argument so timely: it dares to rescue and bring up to date a long dormant, even repressed, research territory for architects—one that was once very fruitful. Through no coincidence, the first essay of the book addresses the big questions posed by John Hejduk when recasting the curriculum for the Cooper Union. Despite his relentless efforts to explore other fields of knowledge and artistic creation, the American architect always discovered a reassuring home in architecture’s spatial roots, which allowed him not to lose focus in his attempt to unravel the heart of our discipline.

This focus was soon to dissipate on a global scale. Since the 1970s, there has been a growing tendency in architectural writing to evade a direct confrontation with terms such as “space” or “form,” sheltering discourses under a plethora of references to, and loans from, other fields—from anthropology to biology, sociology to politics, philosophy to cultural studies, the list goes on. This increasing need to expand the limits of architecture—which, in certain contexts, can be largely understood as a reasonable reaction to the American formalist tradition—has in turn given way to a generalized a-theoretical phase in which theory is merely evoked “as a phantom that haunts us,” as Philip Ursprung put it. Neither confronting architecture from within nor the phantom of theory or criticism seem to disturb Aragüez, as he makes clear in the essay titled “On Architecture’s Metacriticality.” Instead of theory, however, he offers a form of architectural knowledge that brings together the act of thinking about buildings and that of actually conceiving and designing them. This spirit was already present in Aragüez’s previous project, The Building, but receives even more emphasis in this latest work.

Many of the essays begin by identifying a strong statement about architecture that has become commonplace; or a complicated term that is either ill-defined or overloaded; or, an established dichotomy derived from simplistic binary thinking. These issues are placed on the dissecting table to be examined with sustained rationality and one clear goal: to find a missing gap within the state of the art, an opportunity “to conjure up an alternative to the status quo.” This approach draws the reader, among other things, into the ins and outs of language, proving that even the tiniest linguistic nuances may carry significant conceptual implications. Great examples of this understanding of language as a vehicle for thought can be found in the essay on “the organic” as well as in the carefully crafted index, full of concepts instead of just people and places. When dealing with oppositions specifically, the critical challenge lies in treating the two sides as dynamic entities that may dissolve, join, collapse, form a new synthesis, or just coexist in an irresoluble tension. Whether semantic/syntactic, geometric/organic, extrinsic/intrinsic, formalist/idealist, or representative/organizational, dualities allow the author to delve into the history of ideas—within and beyond the architectural field—in a productive and compelling fashion.

With illuminating effects on the construction of Aragüez’s discourse overall, “Sponge Territory” is a monographic essay on Toyo Ito’s Metropolitan Opera House in Taichung. The findings articulated in this piece seem to inspire the essay immediately following, “Critical Imageability,” where the author explores an alternative to what he calls a “[post-modern] representational break grounded in a duality between building-as-representation versus building-as-spatial-organization.” By giving name to specific spatial qualities, such as “sponge surface” and “spatial reciprocity,” Aragüez’s analysis praises Ito’s building for its capacity to materialize the collapse of the above-mentioned duality, its identity founded in the precise synthesis of representational character and spatial disposition. It does not matter if the outcome as-built displays some doubtful details or inconsistencies, from its harsh relationship to the city, to the clumsy flat slabs that jeopardize the fluidity of the internal space. After all, the final credit goes to “the important territory (that this building) delineates,” within the confines of “dispositional thinking.”

Ultimately, that seems to point to the final scope of Spatial Infrastructure: to delineate uncharted territories for quite a “classic” yet vital realm of architectural thinking. Moreover, the author seeks to provide a tool for thinking about tools—a sort of meta-design device that allows for practice and theory to become intricately intertwined. In some fundamental manner, once again, that contribution involves here the collapse of problematic oppositions as a way to reshape our persistently binary minds and envision the future of architectural thinking afresh.

Guiomar Martín is an assistant professor at ETSAM Madrid.