The following interview was conducted as part of “Building Practice,” a professional elective course at the Syracuse University School of Architecture taught by Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller, and now an AN interview series. On September 26, 2019, Genevieve Dominiak and Hannah Michaelson, students at Syracuse University, interviewed Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb of the New York-based New Affiliates.

The following interview was edited by Kyle Miller and AN for clarity.

Genevieve Dominiak and Hannah Michaelson: Thanks for joining us! We know that you met in graduate school at Princeton. We’re curious to know how you two came together to start an office. Is it something that you had been planning for some time, or did it happen rather quickly?

Ivi Diamantopoulou: It was quite organic for us. We started very informally. There was a project we started looking at together while working for other offices. And it made sense: it was fun and interesting and exciting, and we wanted to keep doing it. So, we had a moment of realizing this is what we wanted to do. We convinced ourselves that if the infrastructure was there, everything would work out. We had no clients, but we had insurance! It’s been about three years now, and it’s somehow worked out.

Jaffer Kolb: Part of it was working through an inquiry into the formula of how practice works. For us, it was really about coming together as two people who are very different. Ivi had a much stronger background in practice, and I came more from curating, writing, and working on installations. We wanted to use these differences to test architecture as a variable condition that we could play around with using the small office model to combine teaching, practicing, writing, and research. But instead of trying to do it all at once, we use every opportunity to trial various combinations of our skills.

From residential work to installations to warehouse conversions, your portfolio is full of very diverse projects. Do you have a unique approach to each project type?

Jaffer: We really like working on different kinds of projects. Within each project, we are less concerned with typology than we are with a general approach to design. We’ve designed a lot of exhibitions and residential spaces. The projects are unique, but it’s not necessarily because they have different programs or are different types, it’s more because we bring different interests at the beginning of each project. We like those strange hybrids, which we seek out regardless of the project.

Ivi: But there are differences between the exhibition projects and the residential projects. They each have very different timelines and budgets, and different degrees of openness to experimentation. For example, if we want to test a particular material application, we can do that in an institutional context more easily, because those projects are often fast and temporary. And then we can use that material again in a project that is commercial or residential, where we generally have less room to take risks and experiment. The two different speeds at which projects get developed generate slightly different approaches and opportunities.

We know that you both teach. How do you balance your time between teaching and practice? And regarding your identities and the identity of your practice, do you view one of these venues as primary? Who do you consider your primary audience?

Jaffer: These are good questions. We’re really interested in academia and are grateful for opportunities to teach and be included in academic events such as this interview series. We both teach, but teaching is secondary to our practice. For now, neither of us are looking for full-time jobs at universities. Practice comes before teaching, at least while we’re figuring out how to run the office. Hopefully over time we can refocus our attention back and forth between the two, because we find the dialogue productive.

Ivi: We come after a generation of architects that somehow managed to juggle everything at once—not only teaching and practice, but also academic administration, curation, experimental work, writing… It seemed admirable, but also overwhelming to us. We’d like to start with practice… we are invested in making it work, while maintaining a loose relationship to academia. We see it as a space where we can observe, grow, develop expertise.

Jaffer: And to answer your question about what audience we’re catering to or speaking to… on the one hand, we want to be recognized within our peer group and in academia, but most of our work tends to have an element of public engagement. Right now, we’re putting a lot of our energy into communicating with the city and working through formats that have broader audiences. It’s very difficult to make something interesting to the discipline of architecture and architects specifically, while also communicating broader principles to a larger audience. When we do our best, we’re doing both.

Regarding your interest in construction and demolition material waste and reuse, do you think about the second life or the material life cycle of your projects while you’re designing them?

Ivi: Absolutely. This is something that we have been looking at very closely, especially with exhibition design. It’s only through our ongoing involvement with these types of projects that we’re able to look closely and internalize such issues before we begin to address them through design. We recently did a show on Leonard Cohen for the Jewish Museum in New York, and at the same time were collaborating with the city’s Department of Sanitation to understand museum waste. From the outset, we looked for materials that could be taken apart and reused after the show was over. This changed both the kinds of finishes we were using and how we detailed their installation. We made sure that everything resisted wear and was easily removable. Following the exhibition, most of those materials were donated for new uses all around New York City. I’m super excited about that!

Jaffer: Our reuse projects are in this really weird niche, where we’re mostly looking at what architects make and how we produce waste—looking at what we produce that’s superfluous, or excessive—and to treat that as inherited material. But this work is less about responsibility and more about methodology—investigations into local economies and material flows. I don’t want to pretend that we’re experts in reuse. We use these projects to think about detailing and assembly, but also to think about how architecture operates as a narrative within the city. In this sense, the second life might intersect with things like form or program as a means of perpetual reinvention.

We’d like to ask some questions about the Tunbridge Winter Cabin in Vermont. Did your experience in exhibition design influence the design of this house?

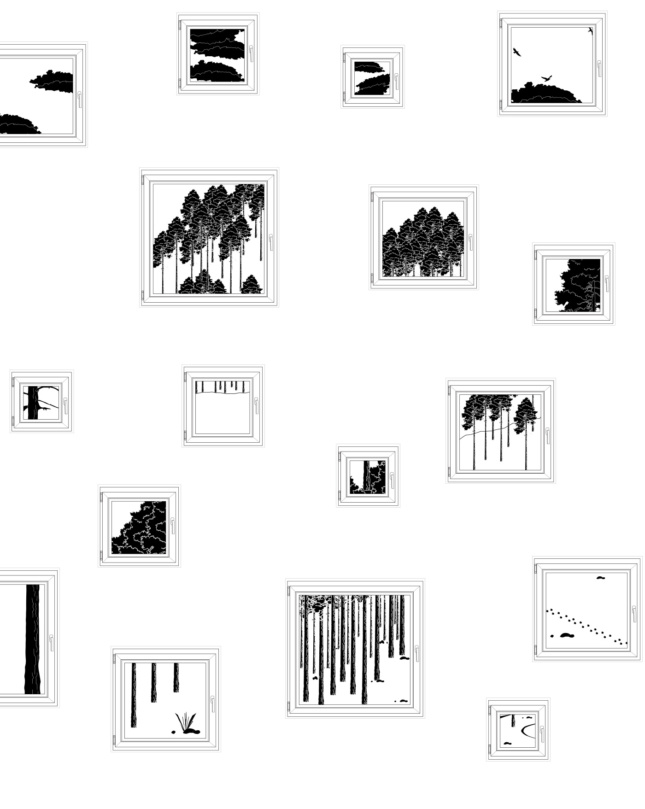

Jaffer: To start, we really wanted to avoid the typical modern cabin design and be strategic about how we used framing and aperture. Those motivations come from exhibition design… thinking through perspective as an immediate visual issue. We were interested in how different events would unfold in a contained space, as a time-based medium. We coupled an idea about how one moves in a domestic environment with an idea about how to organize an exhibition relative to framed views and orientation. We were thinking a lot about landscape painting—not just about the content of the image, but about arranging landscape paintings which become interior elevations.

We read that the project was designed and constructed very quickly. Did the pace of the project limit your ability to explore different ideas? What was your relationship with the client throughout the process?

Jaffer: It was very fast. It was also very collaborative. Sitting together with our client, we would literally project a Rhino model on a wall and rotate around to ensure that there was no room for misinterpretation. Issues could be addressed, and problems could be solved together in real time. We did not follow the typical model of preparing polished presentations, receiving feedback, spending a week making revisions just to present again. How we work is honestly a bit messy and impromptu. We’re more interested in what we can learn through collaboration with contractors, clients, and even with living artists in our exhibition projects. We understand working with others as a chance to express something about a collective, even if just for a moment. We’re not here to push an agenda.

Ivi: Working on the house was very fast, informal, and conversational. We didn’t have the luxury to study every design detail or to iterate through thousands of options. We were lucky to work with a contractor who was a great communicator. We often joked that he was like a 3d printer—we would sketch something on site and then a day later it would be built. The process was easygoing and laid back: let’s do it this way, let’s try this other thing, let’s improvise. It’s a big part of how our practice was formed, in terms of our early experiences.

Can you give an example of this? How did collaboration play a role in the development of the cabin?

Jaffer: We didn’t go in with a 70-page construction document set and ask the contractor to execute our drawings. We knew the form of the cabin and we had an idea about what the interior and exterior elevations would look like. It’s not that we came with nothing, but we were trying to draw from his expertise as someone who’s been working in Vermont his entire life. We had some ideas of how we wanted the project to look and how interior spaces would relate to one another, but we needed guidance from a local expert, especially when it came to details and environmental issues. One example was with the baseboards. We kept resisting certain tolerances that he insisted on given Vermont’s extreme temperatures, but in the end, we followed his recommendation. He did it as a custom inset baseboard, though. While we listened, we also never wanted to go with an easy default.

Ivi: Working with him, we were able to strike a balance between an exquisitely designed house where every detail and material transition and connection is considered and precious, and a house that is durable and casual and provides a sense of comfort. It’s kind of funny for us to realize that with the Vermont project, we established a standard for our practice where we leave certain things deliberately incomplete. We have a client right now—a graphic designer—who we leaned on to help lay out a pattern on a large custom millwork element of his home. We had a conversation where we told him… “You know, you do this for a living, you should just do this.” We should do this together. This is not a matter of us knowing better than anyone else.

Did your interest in material life cycles, waste, and reuse inform the design of the winter cabin?

Ivi: Yes, definitely. There’s a material sensibility in the cabin. For example, the baseboard material is all recycled plastic. That plastic comes in large sheets, so we were compelled to make room in the design to retrofit all off-cuts—you’ll see it pop-up between window sills and panel frames to avoid excess waste. Also, we worked to incorporate passive strategies that will enable the house to climate control itself through the winter, even going back to the windows being smaller framing devices instead of giant picture-planes. It’s a bit introverted, a bit closed.

Jaffer: I would say… unfortunately, not as much as it should have. For example, there was nothing on the land when we got there. In order to make a half-mile driveway, we had to cut down a lot of trees… which is not a huge deal because there are a billion trees in Vermont. We also had to blow up a lot of ledge, but that ledge became the front porch and paving. The trees have all been milled and that wood is going to be used on the main house structure. There is a sense that everything that gets destroyed on the land to clear space for the house gets reused in the house. It’s almost like a semi-enclosed material economy. But I wouldn’t take credit for this phenomenon. That came from the contractors and landscapers.

Where do you see yourselves in ten years? Do you hope to continue to work on smaller projects or would you like to evolve into a practice that can take on bigger projects?

Ivi: I don’t even know if the two of us are on the same page, but I can tell you what I hope for. I imagine that these two worlds, institutional and private; temporary and permanent, might begin to move closer to one another. I’d love to think that our ongoing affiliation with the art world and our increasing expertise in design and construction could enable us to work on projects that are larger and maybe more permanent.

Jaffer: Ten years is a long time from now! The easier answer is for the next few years. Originally, I had always imagined that we would keep growing. More recently, I’m resisting the desire to grow. We are still exploring how to create an interesting form of practice. If you’d asked us this question two years ago, I would have said that in ten years, we’re going to be 45 people and we’re going to have large commissions. After being in this for a couple of years, I actually want to slow down and invest more time and energy into figuring out how we can do better work before we start getting more work.

We’ve been concluding the interviews by asking everyone the same question… What’s been the most rewarding moment as a practice thus far?

Ivi: Not quitting on ourselves! Every single day we decide to not apply to work for a corporate office is very rewarding.

Jaffer: I’m going to give an earnest answer: I think this moment is one of the most rewarding. I’m being very sincere. When I woke up this morning, I was thinking about how meaningful it is that our work can sustain the interest of a class, that it can sustain a close read, or prolonged attention. It’s incredibly gratifying!