It has already been a busy year for creative director and set designer David Korins. Hamilton: The Exhibition, which Korins served as creative director of, opened on April 27, bringing an immersive 18-room exhibition to Chicago’s Northerly Island; that same week, the stage adaptation of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice, with sets designed by Korins, opened in New York on Broadway.

Hamilton: The Exhibition dives much deeper into the life and history of Alexander Hamilton, the person, than the stage show (which Korins also designed the set for) and expands on topics that were overlooked in the musical, such as slavery and Hamilton’s legacy after his death.

To help guide fans through the exhibition, an audio guide narrated by original cast members Lin-Manuel Miranda (Alexander Hamilton), Phillipa Soo (Elizabeth Schuyler), and Christopher Jackson (George Washington). The show, which is currently staged in a 35,000-square-foot black “hangar,” was designed to be mobile and will eventually pack up and leave for other cities after an undetermined run time in Chicago.

The $13.5 million exhibition actually cost $1 million more to open than the musical it’s based on, but much of that owes to the show’s high level of technological integration and attention to detail. Guests can take an interactive tour through famous scenes from Hamilton’s life, engage with games, and even watch a 3D version of the musical’s opening as it was performed in Washington, D.C., with Miranda at the helm.

Tickets for Hamilton: The Exhibition are $39.50 for adults and $25 for children.

Korins also served as the creative director of Treasures from Chatsworth, a show at the renovated Sotheby’s New York headquarters that will run from June 28 through September 18. Art from the Chatsworth House in England, owned by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, will be juxtaposed against supersized versions of minute details from the home that could easily be overlooked.

AN recently caught up with Korins and asked him to break down how he was able to realize his two most recent projects. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How did you go about translating a show that works around one set into an exhibit with 18 full exhibition rooms with branching paths and interactive multimedia?

David Korins: Well, it was harrowing. Although, the Hamilton exhibition is decidedly not Hamilton, the show. We had way more content to deal with.

In a way, using Hamilton, the man, as our through-line and as our lens into early America was helpful because it helps crystallize the story that we’re telling. There’s enough information about the founding of early America that we could have made an exhibition just on George Washington, or Thomas Jefferson, or James Madison, or anyone.

In a way, the stage show, which obviously spans about thirty years across countless locations was one thing. But we had to use a whole bunch of artistic compression in order to make that show a dramatic piece of theater. What we wanted to do with the exhibition museum was to really able to go in to deeper and wider into the entire story of America and really kind of right the wrongs of the dramatic lives that we tried to mimic in the show. It’s easy conceptually to say, “let’s expand this thing into 18 or 20 galleries” because there’s just so much more information.

It was nearly an impossible task artistically to try and actually execute it because a stage show has no ceiling on it, there’s no fourth wall, there’s no wall between the audience and the performers. In this exhibition, every one of these things is a complete room.

I know it’s more about Hamilton the man, but it does seem like some of the rooms, this writing desk room for instance, tie into songs from the show. How did you balance how much of the musical should be in the exhibition versus how much should focus on history and Hamilton’s life?

DK: First of all, we’re not trying to distance ourselves from the show. We, in fact, have a completely remastered, re-orchestrated, rerecorded score in every one of the galleries. I think if you look at the New York City gallery, it is very reminiscent of the architecture that I designed the stage show with.

I would say that much of the spaces employ the use of very abstract, theatrical design, visual vocabulary. Part of that is because I’m the one designing it, creating it. A part of that is because you can’t realistically recreate all these historical locations. Nor do I think that that would be necessarily interesting. I think one of the things that we told ourselves in the very beginning of this process was to try and do what only we can do.

And then there are moments that are wildly abstract where there are swirling pieces of parchment paper floating up into a work cloud over your head. So we tried all that we could do, and I thought for two years about what I want each one of these rooms to feel like and what story we are trying to tell.

Changing gears to Beetlejuice—that’s a movie where the scenery is constantly shifting around. Looking at the photos from the set, it seems like you had to reinvent the same stage multiple times during the show. How did you translate Tim Burton’s aesthetic for the stage without reusing it wholesale? It doesn’t exactly match the house in the movie, but I see there are references to his other work sort of scattered around.

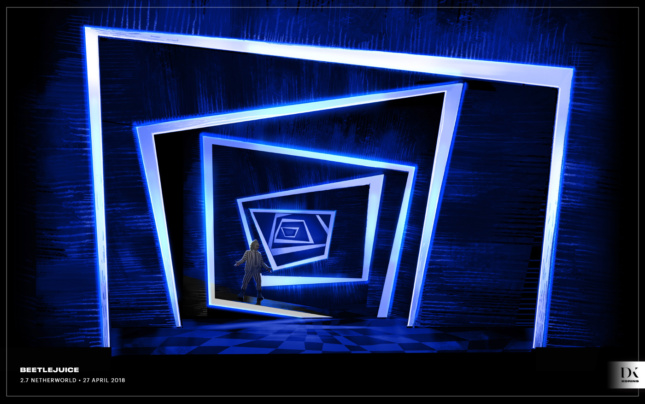

DK: As far as technical difficulty, I will agree with what you said, and I will tell you that the show is by far the most technically challenging thing I have ever done, and it’s by far the most technically challenging show I’ve ever seen.

If the Hamilton exhibition was the biggest and most ambitious project I have ever worked on, which it certainly was by a lot, Beetlejuice was the most complicated one. That show, every single piece of scenery has a light in it, a special effect, a magic trick, a puppet pole, a speaker. Some crazy thing going on inside of it.

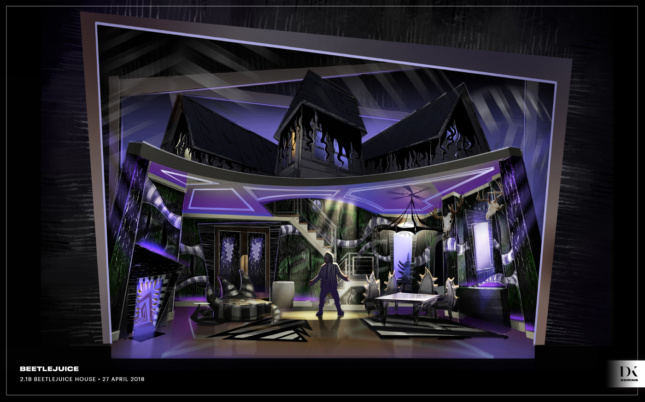

How do we incorporate the world of Tim Burton? I think that Tim Burton is one of the great visual artists of our time. I think when you are asked to do a Tim Burton project you have to honor it and acknowledge it and try to keep up.

Beetlejuice the musical is very different than Beetlejuice the movie. The thing about it is we have a whole bunch of different physical parameters, so we have to take those into consideration as opposed to making a movie. First of all, the play runs eight times a week and we can’t cut away, we can’t dissolve, we can’t have a puppeteer just out of frame or anything like that. We have to make this thing work seamlessly for a bunch of live people in a room.

Beyond that, I thought that it would be interesting to honor Tim Burton’s kind of overall visual aesthetic, not just the Beetlejuice one. You have Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Coraline—we have tons of references. So we’re storytelling in a very different way. You can’t have an actor be in a different costume every single scene. We’re telling the story at a much broader, more muscular gesture.

How did you design a set that would be so easy to shift in such shorter amounts of time?

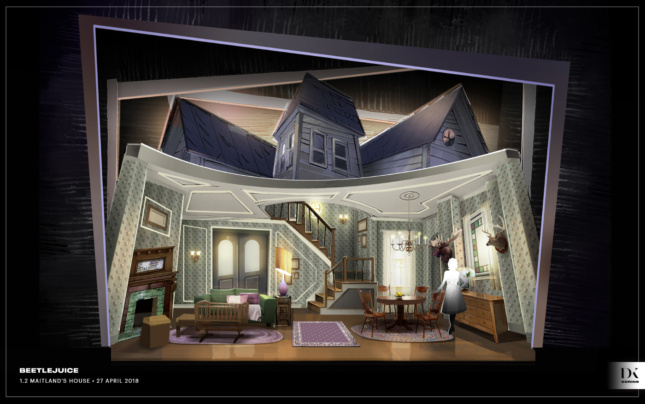

DK: I guess the short answer is: we’re geniuses. Just kidding! I think it was very important that the Maitland’s home felt different aesthetically than the Deetz’s home. And that the Deetz’s home felt different than the Beetlejuice home.

So we had to ask ourselves, what could we possibly change in six minutes of stage time, or ten minutes of stage time? And how do we do that?

We came up with a really ingenious wall system that we would be able to sub out. The changing of the furniture and the mantles and the window frames and the light fixtures is exactly as you would imagine it. A lot of manpower is back there doing these, like schlepping stuff on and off in a perfectly choreographed ballet move backstage. The wall systems are similar. There are prefabricated sections of wall that click in on top of or below other sections. And they literally have to go in and every single section of wall gets changed out.

I see a lot of detail went into even just the small touches in the wallpaper, sculptures, sconces, and all of that.

DK: Every single piece of scenery, every single wallpaper, every single piece of furniture, every single graphic was hand-drawn. And I don’t mean “hand-drawn” like drafted. I mean, literally hand-drawn, even what we drafted with architectural drawings so that they could build them and engineer them.

We then went in and we hand-drew all the wallpaper. We hand-drew all the etching and the lines on all the molding so that everything single thing had a really homemade kind of quality to it.