Perception, space, and technology: Paul Virilio did politics another way. In 1979, with the geopolitical scientist Alain Joxe, brother of François Mitterrand’s future Minister of the Interior, he founded the Centre Interdisciplinaire de recherche de la paix et d’études stratégiques [Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Peace and Strategic Studies] at the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme [MSH] in Paris. A little further up Boulevard Raspail, in 1975, he had become the director of the Ecole Spéciale d’Architecture [ESA]. That same year, he organized the exhibit Bunker Archéologie [Bunker Archeology] at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs [Museum of Decorative Arts] at the request of François Mathey. All this took place only a year after he launched the L’espace Critique [Critical Space] collection for publishing house Galilée with the 1974 publication of the famous Species of Spaces by his friend Georges Perec, an exploration of the infra-ordinary. The groundwork was laid out. “Somewhere Marxists. I was a Gestaltist,” he explained succinctly in 1997.

Space – Distance – Destruction

People do not always remember that one of the authors of the suicide attack on the towers of the WTC was an architect. “Can we still listen to the builders when the demolishers are recruiting everywhere?” Paul Virilio was intent on bringing this question to mind in the preface he wrote in 2004 to A Civilian Occupation, the French translation of Eyal Weizman and Rafi Segal’s work on the politics of Israeli architecture. Concerned about the false proximity of globalization, the philosopher observed in this preface how some of the solid reference points that he had constructed since Lost Dimension were now faltering. Like this one, first of all: “The former geopolitics of territorial space that provided nations with the necessary intervals of space between different states is now being replaced by a METROPOLITICS of chronic instantaneity and permanent confrontation.”

Anxiety is native to Virilio. It took hold at the same time as the fascination he experienced at the time of Liberation: the young refugee boy from Nantes who had just experienced the partial destruction of his city through bombardment embarked on a train to the edge of the Bay of La Baule, France. The beauty of the beaches and the horizon of the Atlantic coast struck him at the same time he discovered with awe the fortified line erected there by the occupiers: “The bunker is the last theatrical gesture in the end game of Occidental military history,” as he wrote in 1975. Virilio was a planner who built concepts like a philosopher and liked to test them—and contrary to what Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont have said, metaphor is useful for concepts. Yet he experienced and suffered geostrategy and geopolitics before thinking them.

Vigil

Virilio was an anxious watchman, always on alert, but he was by no means conservative. While his observations are similar to those of Françoise Choay, another urban philosopher who is part of the same generation, their subsequent aesthetic positions and conclusions diverge quite significantly. While each one recognizes the power of forces of deterritorialization at work in our societies, one calls somewhat simplistically (if we are accelerating, we should slow down) for a supportive, banal, and even resolutely old-fashioned architecture, whereas the other has renounced his interest in formal research. He was one of the first to uncover the ambiguities of Albert Speer, the successor of Fritz Todt, the man of total war and the architect of the 1,000-year Reich, the builder turned destroyer. Virilio was against towers, or against the ideology behind their erection—tourelisme [towerism] as he called it—because he discerned their naiveté and was convinced that the future of cities will not be in their skyward dimension.

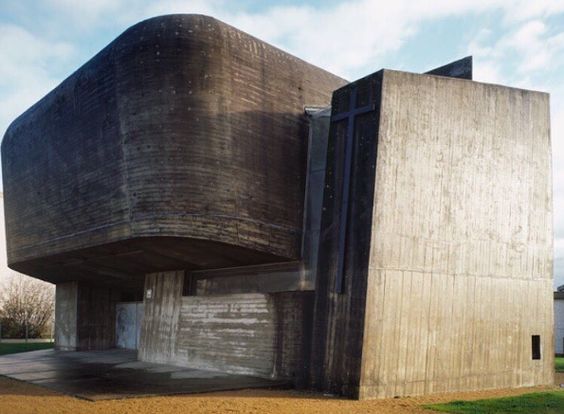

He reminds anyone willing to listen that he worked with the architect Claude Parent [1923-2016] 50 years ago on the “oblique function” with the idea of raising the ground: moving beyond orthogonality, using gravity to play on the duality between synclinal and anticlinal, and finding a continuity of ground in elevation. A third order, the oblique, would succeed the horizontal order of rural habitats and the vertical order of urban dwellings in response to the principle of “habitable circulation” where the bodies of inhabitants become locomotive and take advantage of the energy created by oblique disequilibrium. Created in 1963, the duo of Architecture Principe only completed two buildings according to these principles: a church in Nevers, France, and an aerospace research center for Thomson in Vélizy near Paris. Nevers and Vélizy, two small towns, two places that few people pass through by chance. In Nevers, a two-ventricle grotto, a cryptic church dedicated to Saint Bernadette (Soubirous) of Lourdes; and in Vélizy, a workshop where researchers design missiles! A church and a gates of hell—no one could accuse Virilio of incoherence.

Jean-Louis Violeau is a sociologist and professor at l’École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Nantes. He lives between Saint-Nazaire and La Baule.