What is creativity? Who are the creative geniuses among us? How can the talents of the creative individual be identified and cultivated?

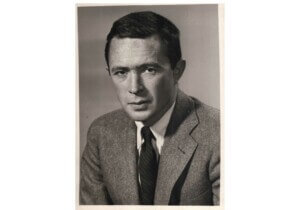

These questions were asked about architects six decades ago in one of the most comprehensive studies of creativity ever done. The work was carried out by a talented cadre of psychologists led by director Donald MacKinnon of the University of California’s Institute of Personality Assessment and Research with support from William Wurster’s Berkeley architecture faculty.

It was part of a five-year research program funded at a cost of 1.4 million in today’s dollars by the Carnegie Corporation to measure the personality characteristics of a range of creative types. The hope was that the “creative promise and dormant potential” of individuals could thus be identified and encouraged to blossom for the benefit of society as a whole.

Given the major investment of time and money involved, it is curious that relatively few outside the world of personality research were aware of the architect study and that no comprehensive account of the work has existed outside the files of IPAR until now.

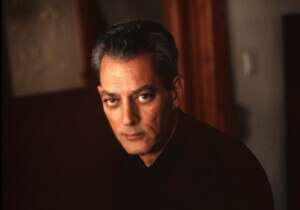

Serendipitously, the forgotten records of the study were discovered languishing in IPAR’s archives several years ago by Bay Area author, architect and educator Pierluigi Serraino whose painstaking efforts bring them to light in an engaging and fascinating history, The Creative Architect.

Serraino’s attractively packaged volume has a welcoming layout that is easy to navigate. The text is illustrated with abundant examples of original study documents and findings. Practitioners for whom blueprints evoke nostalgia will encounter a color scheme that resonates positively, and those who appreciate a behind-the-scenes approach to storytelling will find his account especially pleasurable. Throughout he lends a historical perspective that provides a unifying context for the information presented.

Serraino traces the origin of the study to several factors: the growing interest in the post-WWII zeitgeist on the creative potential of the individual, the wartime experience of key IPAR staff in administering large batteries of tests under standard conditions for personnel evaluation, and MacKinnon’s fascination with the scope of the architect’s work. In 1962 he notes: “in what other profession could one better observe the multi-farious expressions of creativity?” To him the successful architect is an artist and a scientist, able to juggle and apply “the diverse skills of businessman, lawyer, artist, engineer, and advertising man, to say nothing of author-journalist, psychiatrist, educator and psychologist.”

These influences shaped the design of a multifaceted study in which 40 highly creative American architects from across the country assembled in Berkeley in 1958 and 1959 for three-day sessions to undergo a 20-hour battery of 22 tests and observations covering 7 broad areas. Comparison data were collected by mail from two groups chosen to represent lesser levels of creativity, one with 43 former colleagues of the “highly creatives” and the other with 41 practitioners chosen at random.

Individuals seeking a sense of the culture of architecture of the 1950s will savor descriptions of the often politicized procedures that were followed to select subjects and to design and carry out the study, supplemented by unvarnished views of the quirks and idiosyncrasies of the icons of American architecture, gleaned from their interactions with the research team and each other. Particularly rich are portrayals Serraino has assembled from original records to reveal the formative influences, philosophies, anxieties and inspirations of Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson, Richard Neutral, Eero Saarinen and others.

Serraino transports the reader back in time to group testing sessions in which participants, fueled by well-iced martinis, debated pre-selected questions even as they were being taped and under the intense scrutiny of the full research staff. During discussion their unique personalities emerge: “each participant appears as a distinct character type—Saarinen (phlegmatic), Johnson (socialite), Lundy (lively), Ain (ideological) and Born (aristocratic)—pouring out their worldviews…then engaging in a passionate exchange.”

The independent and competitive natures of participants are revealed by the Mosaic Construction Test, an activity intended to mimic the creation of an artistic product. Participants used their full allocation of time to develop unique and idiosyncratic designs “that held their own,” seizing the opportunity to “make a declaration of their own talent.” Their resulting designs are faithfully reproduced and fascinating to examine.

It is hard to find serious fault with this engaging and sometimes dishy history (two participants were observed cheating on a creativity test), but readers lacking a background in psychological research will find the tangled chapter on study design tough sledding. And many will be disappointed when they realize that tantalizing references made to a twenty-five-year follow-up study of the same subjects are not supported by a meaningful presentation of findings.

Serraino strikes a proper note of caution by acknowledging the shortcomings of the IPAR study—selection bias, self-reporting of key data, choice of testing site, and, of course, the almost exclusive focus on personality traits. On the other hand, he accepts and builds perhaps too readily on generalizations that MacKinnon made about creativity. As a result, the composite portrait of the creative architect with which the book concludes strains to bring a finality to the IPAR work that the original researchers could not.

The IPAR study stands as a historical milestone in the ongoing study of how architects create. Although it cannot be said to have succeeded in its intent, in all fairness, psychology as a whole has made relatively little progress over the intervening sixty years in answering the basic questions posed earlier. What Serraino reveals in his book is that for now, in architecture, the back story is the real story.

And as we have all heard, it’s often the journey and not the destination that matters. Serraino shows what an interesting journey it was.

The Creative Architect: Inside the Great Midcentury Personality Study

Pierluigi Serraino

The Monacelli Press

$45.00

Luigi Lucaccini teaches creativity, innovation, and applied design at the University of San Francisco’s School of Management