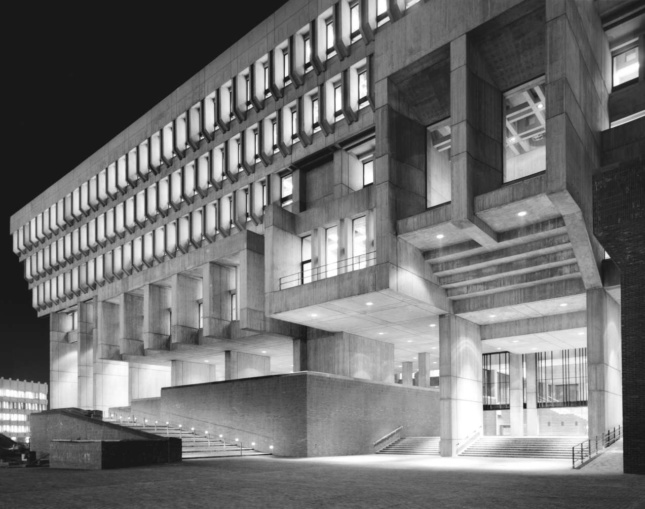

On Friday, March 27, British-American architect Noel Michael McKinnell died of pneumonia after testing positive for COVID-19. He was 84. McKinnell, who was born in Manchester, England, received his initial architecture training at the city university, first traveled to the United States on a Fulbright Scholarship. He studied for his master’s in architecture at Columbia University, which he completed in 1960. At Columbia, he encountered the German architect Gerhard Kallmann, who would soon become a mentor figure. After hearing about a public competition to design a new city hall for Boston, the pair developed a design that drew on elements of the contemporaneous Brutalist movement. They were announced the winners and opened a Boston office in 1962. Their joint practice continues to this day, with a rich portfolio of largely institutional buildings. Yet the firm—and McKinnell—remains associated with Boston City Hall, which celebrated its fiftieth anniversary last year. The following tribute reflects on McKinnell’s complex relationship to the building.

We first met Michael McKinnell and Gerhard Kallmann in 2007 at the outset of the Heroic project, our effort to document Boston’s late twentieth-century concrete buildings, which had become largely unloved. At the time, Boston City Hall was broadly vilified, dismissed as obsolete, and in danger of being demolished. Even in such a moment of threat, Michael was surprisingly open to the idea of his building changing. Far from upholding the original design as a masterwork fixed in time, he explained to us that he felt it needed “younger ideas” and that whatever modifications were in store for its future, they should be “bold and self-confident.”

Younger ideas were part of his thinking from the very start. When he and Gerhard won the competition among 256 entries, Michael was only 26 years old—landing perhaps the most important public commission of the era. Later, as the world was exploding in the protests and civic unrest of the 1960s, this fearless young man explained the design for its enormous lobby to a reluctant City Council as an ideal setting for the democratic staging of dissent. Naive or not in his political idealism, to him it was always the “people’s building.” To us, Boston City Hall reflected the era’s aspirations to invest in the civic realm and the desire to represent a new political order for a New Boston. Michael and Gerhard sought to ingrain these ideals into the building’s DNA, embedding their faith in public life into the matter of its concrete. It would be a framework open to change, as they later wrote, a “robust armature” meant to “engage successive generations of the citizenry in [its] embellishment, decoration, and adornment.”

Our relationship with Michael, which began with distant admiration, grew over a dozen years into friendship. We interviewed him multiple times, gaining a deeper understanding of his work and personality. Starting as an exhibition and later forming a book, we had originally conceived of the Heroic project as a way to recast the public conversation surrounding concrete architecture. In large part because of Michael, the center of these efforts soon shifted from documenting buildings to preserving the voices of those who designed them and the civic aspirations that shaped them—a legacy of ideals rather than a mere history of matter.

Those same dozen years also allowed us to witness a transfiguration in Michael. While we came to know him late in his life, we most often talked about the beginning of his career, before he and Gerhard had fully formalized their shared practice which produced distinguished buildings across decades. He easily re-inhabited that youthful vision—in our eyes, he only got younger as we spoke candidly about his early principles and failures.

Boston City Hall itself underwent a similar transformation. Endangered by one mayor in the early 2000s, we watched with admiration as the building was being feted by another on its fiftieth anniversary in 2019. The event echoed with Michael’s rousing words, delivered in that same enormous lobby, about his undiminished hopes for City Hall’s future. But it was Michael’s own humor that reminded us of the fragility of modernist voices like his, and of their need to be heard again. When the Getty Foundation selected Boston City Hall for a prestigious grant to prepare a conservation management plan (or CMP), Michael was quick to congratulate the team, and then quipped: “I am now in search of a CMP for myself.”

Michael always seemed keenly aware of how the legacies of people, ideas, and buildings were interwoven in time. His final comment in the Heroic interview was on the aspirations of the era to make “something that would endure,” and of the hubris of imagining Boston City Hall as worthy of becoming a ruin in five hundred years. “The making of architecture is imbued with hubris,” he said, “because we challenge our own mortality.” In City Hall, we recognized, he had challenged his. If the building lasted—if the hopes cast into its concrete could be fully realized—so would he.

Warm and gregarious, fascinating and funny, incisive and generous, Michael’s reminiscences were always imbued with meaning. One joyful highlight was a lunch he and his wife Stephanie Mallis invited us to in their Rockport home in 2018, accompanied by the architecture critic Robert Campbell. Sitting with a distant view of the ocean, we shared stories and toasted to lost colleagues over the course of four hours on a beautiful summer Tuesday. The camaraderie, too, seemed like it could go on forever.

Noel Michael McKinnell was born on Christmas Day in 1935 and passed away last Friday afternoon at the age of 84. Through our friendship with him, what began as a fascination with a past era became a commitment to transmit a living set of ideas. We labeled them “heroic” for their civic aspiration, and as a way of acknowledging the hubris that characterized so many of those ambitions and the figures who advocated for them. But Michael’s lofty ideals were always tempered by his youthful energy and his mischievous sense of humor. If we ever got too serious, he liked to rib us a little. With a glint in his eye, he would delight in proclaiming: “They used to call me Brutalist. Now I say ‘I’m Heroic!’”

Chris Grimley, Michael Kubo, and Mark Pasnik are authors of Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston, published by The Monacelli Press in 2015. Grimley and Pasnik are principals at the architecture and design firm OverUnder. Kubo is an assistant professor at the University of Houston.