The following interview was conducted as part of “Building Practice,” a professional elective course at Syracuse University School of Architecture taught by Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller, and now an AN interview series. On September 19, 2019, Tianyi Hang and Yifei Luo, students at Syracuse University, interviewed Paul Andersen, principal of Independent Architecture.

The following interview was edited by Kyle Miller and AN for clarity.

Tianyi Hang and Yifei Luo: In this interview we’d like to focus on a few recurring themes in your work—repetition and difference, and engagement with the ordinary. Before addressing these issues, we’ll begin with a few questions about your general approach to practice. So, to begin… What does it mean to practice architecture?

Paul Andersen: Generally speaking, I think that to practice architecture is to contribute something to the discourse—in the form of models, essays, drawings, gossip, or buildings. The goal is to open up new ways of thinking and designing, which is different than, say, practicing piano, which is more geared toward refinement.

What do you think makes your office unique when compared to other emerging offices?

The most obvious difference is that we’re in Denver, which is on the fringe of the field, at best. When it comes to buildings, Denver has a lot of corporate schlock. But it also has some pretty good suburban architecture, which influences the office’s culture and work. The suburbs’ pop sensibility is fantastic… it tends to be accessible and unique, so we use it as a model for how we work. Pop practices accept that their work isn’t essential. It acquires value when people like it—and those people might be friends, experts in the field, the general public, or any number of groups. This seems like a good approach for architecture, too. If people don’t absolutely need great design, we can feel free to do strange, irrational projects… and even to fail. We also borrow material from the suburbs. Sometimes we incorporate everyday objects, like giant party balloons, statues, and letterforms. In other cases, we use a familiar material in an unorthodox way, like in the project that we’re doing with wood framing at the US Pavilion this summer with Paul Preissner. And occasionally we look for new design principles in idiosyncratic examples of ordinary suburban buildings.

Who commissions your work? Do you have to spend a lot of time finding work or do clients come to you?

Some of both. There is a lot of chance involved in finding the type of projects that we enjoy. Some offices have a structured approach to finding work, but I think that sometimes it’s just a matter of being in the right place at the right time. A related issue is the low percentage of projects that we actually finish. Of all of the projects that we’ve started, only about 10 percent to 20 percent have been built. In the end, I’d say that finding clients who want to do the same kinds of things that you do is what matters most.

What types of projects do you hope to work on in the future?

More houses and arts projects would be great. Mainly I hope to keep designing, curating, and writing.

We’d like to ask some questions about the Motherhouse project, which we understand was commissioned by your mother and recently completed construction in Denver. Congratulations! On your website, you reference plan diagrams of houses completed by Palladio, Le Corbusier, and Ungers. What is the role of these projects, and of precedent, in the design of Motherhouse?

I was looking at the Ungers House in Cologne before we started the Motherhouse project. I often hear other architects describe it as a minimalist project. Even Ungers described it as an experiment in making a totally abstract house… where you can’t recognize materials or scale or even tell the top from the bottom. Oddly enough, the minimalist tilt is completely undone when you look at the plan, which has an outrageous number of doors. I think that there are 178 doors… including six in the hedges. So, there’s the minimalist exterior in contrast with an interior that’s beyond excessive.

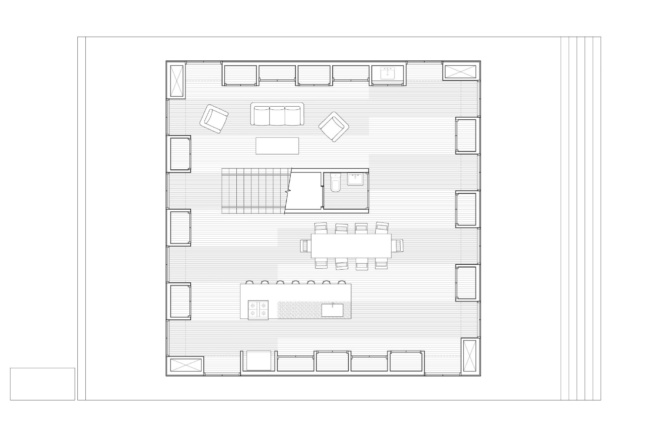

I like the bizarre combination of rational and irrational design in that house… it turned us on to some aspects of Motherhouse. At the same time that I was looking at Ungers, I was also looking at houses in Englewood, Colorado, that are quirky, very odd 1960s houses. The point of Motherhouse was to merge these two references… to do a suburban American version of the Ungers house. The walls have the same thickness as the Unger’s house, but instead of that thickness being used as a set of foyers, it’s used for closets, which we needed because we couldn’t build a basement on that lot. The water table is a bit too high. So, the first floor of the house ends up being a single room lined with doors—no walls. The second floor is a more or less rotationally symmetrical arrangement of rooms that all have different ceilings. Throughout the house are examples of excessive repetition… in the gables, doors, stairs, and colors, for example.

Was the open ground floor plan a requirement set by your mother?

My mother will not actually live in the house. As I’m sure you know, there is a tradition of architects early in their careers building houses for their mothers, because it’s a moment when your mother is the only one who thinks you can actually do whatever strange thing it is that you want to do. So, Corb designed and built a house for his mother; so did Richard Rodgers, Robert Venturi, Charles Moore, Harry Seidler, Charles Gwathmey…. this list goes on. In my case, my mother didn’t want a house for herself, but she wanted to support me by commissioning the design and construction. We’re going to sell the house; and as soon as we sell it, we’ll do another one. It’ll be an ongoing project.

Earlier, you mentioned that you’re drawing inspiration from the suburbs. What has been the response to Motherhouse from people living in Denver? Do they see the connection between your unique design and some of the familiar aspects of houses it’s inspired by?

So far, most people’s initial response is usually confusion, even dislike. The work that we do in schools gets farther out of the mainstream than we realize sometimes. It could be that there is something unnerving when an architect messes with the familiarity and comfort that people expect in a house—especially in a suburban house. So, for example, the extra flat facade is a problem for a lot of people. They don’t know what to make of it. However, when I get a chance to talk to people about the house, to explain the design strategy, they usually come around. They understand that the stripes on the facade and the 12:12 gabled roof are already in the neighborhood, in Victorian bungalow houses that have been there for a century. They can see that this house is just a different version of the typical houses in the neighborhood.

Across many of your projects, we see recurring use of strong geometric figures in plan and three-dimensional figuration… as opposed to complex three-dimensional form. Can you talk a bit about your interest in figuration? Are these features intentionally incorporated?

It’s a pretty deliberate reaction to things that I learned back in graduate school at UCLA. In my second year, I got a chance to work with Greg Lynn on his Embryological Houses. He had a brilliant argument regarding variation and difference, how the project inverted the Modernist kit-of-parts logic… but I always thought that the argument would have been stronger with more figurative geometry. Working with geometry, and curvature in particular, is an interest that continues to play out in many of our projects. Teaching at the University of Illinois – Chicago, where a focus on figure and shape has been an important part of the discourse during the past decade has definitely helped. For years, we intentionally limited figuration to the plan in our projects. Motherhouse is the first one where we are more aggressively pursuing figuration in elevation and section.

You mentioned that only 10 to 20 percent of your projects get built. What happens when a project stops prior to completion? Do ideas find their way into other projects? And what about the temporary installation projects… do those concepts evolve into building projects? Do you reuse the materials?

A few years ago, Paul P. and I designed a structure made of two barns for a contemporary arts festival in Denver. The barns were only up for a day… actually more like eight hours. They were made out of an off-the-shelf steel barn panel kit. For years I’ve been trying to build houses made of the same system, just assembled differently. It hasn’t happened yet. In other projects, we’ve gotten all the way through construction documents before cancellation. There are many ideas from those projects that we hope to incorporate into future work. Even with projects that don’t get built, there is research that we do in terms of material or structural systems that will become valuable again someday. There are also some bubblegum projects… I have yet to build a cruciform column out of bubblegum, but I will someday.

In another interview, you stated that you’re not as interested in creating good architecture as you are in creating interesting architecture. What did you mean by that?

What I meant by good was moralizing. There’s a lot of talk these days about what architects should be doing. I got into architecture for the complete opposite reason. I like the idea that if you’re a good architect, then you’re figuring out what you shouldn’t do. You go against the grain and attempt to open up new ways for others to see the world. Sometimes, the only way that can happen is by pursuing the unfamiliar and the unexpected, and even the uncomfortable.

What has been the most rewarding moment in your professional career, or what’s the most rewarding aspect of practicing architecture?

I really enjoy the surprises when I see a project get built. You know… there’s stuff that you drew and modeled and imagined, and then all of a sudden, there it is. But sometimes it isn’t what you expected. It turns out to be weaker or stronger in some way. In the Motherhouse and a few other recent projects, we’ve been trying to see if we can produce qualities through excessive, consistent repetition, rather than variation, or repetition and difference. We don’t really know what kind of sensibility will come out of it until it’s built. So, we do it and we get to find out. I really love that. And also, that in any given day, we might deal with bubblegum, framing plans, and Catholic theology, all with equal seriousness and irreverence.