The following interview was conducted as part of “Building Practice,” a professional elective course at the Syracuse University School of Architecture taught by Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller (and is now an AN interview series). On October 10, 2019, Felix Samo and Tirta Teguh, students at Syracuse University, interviewed Kutan Ayata of the Brooklyn-based Young & Ayata.

The following interview was edited by Kyle Miller and AN for clarity.

Felix Samo and Tirta Teguh: We’ll start with an easy one… What does it mean to practice architecture?

Kutan Ayata: Do we have three hours?! Actually, this is something I recently discussed at length in a lecture titled, “Practicing-Teaching.” These two modes of operation are inseparable for us, as well as for many of our colleagues who established their offices after the recession in 2008. We actually started our office three months before the recession… timed perfectly! We quickly realized that traditional practice was no longer going to be viable for us. So, our practice includes teaching, our teaching includes practice. They’re inseparable. Practicing architecture is pedagogical. It’s about an exchange of ideas. Because we are primarily supported by teaching salaries, we can be very selective when it comes to our practice. Our office is a space where we actively explore our evolving curiosities about architectural potentials without too much compromise.

Was starting an office something that you always wanted to do or something that happened unexpectedly or circumstantially?

It’s both. I always knew I wanted to have a practice of my own. Michael [Young] would say the same thing. We both worked for about eight years for others before starting our practice. The way we started was incredibly casual. Michael and I lived on 14th Street in Manhattan after we graduated. We met up one night for drinks and had an unplanned discussion about starting a firm. We studied at Princeton at the same time and we worked together at Reiser + Umemoto. We got along, and we enjoyed working together. At that time, forming a partnership was almost more of a social decision than a professional decision. The spirit of that moment is maintained—we enjoy working together which helps us stay motivated. The answer is “yes” to both parts of the question: the practice came about rather unexpectedly, but it was also very intentional.

What was your experience of the financial crisis in 2008? How did it affect the way you and your peers practice?

That was a defining moment. In hindsight, it was the best thing that could have happened to us. We had real projects, real contracts, projects going into construction… and all that basically disappeared overnight. All of a sudden, no job, no income. It was obviously a moment to freak out. But we found ways to deal with the situation. That’s when I started teaching, which changed the way I look at the world. The crises gave us an opportunity to slow down and contemplate our position in the discourse of Architecture. We began developing self-generated speculative projects, which, to this day, serve as the conceptual basis for much of our work.

Concerning success you’ve had as an architect and as an office, do you attribute these moments more to fortunate circumstances or to skill and perseverance?

Again, both. Nothing happens without hard work. In this last 10 years, both of us have started families, had kids… our lives got more and more hectic. We have less and less time to work. Additionally, we often teach at multiple schools each year and every day of the week, which is not common, nor easy. Before Michael earned the tenure-track position at Cooper Union, he was jumping around quite a bit—sometimes teaching at three schools in three different states in one semester. We figured out a way to make our work time more efficient amongst all those scheduled pressures. Success doesn’t come without a tremendous amount of hard work, but it also doesn’t happen without luck. We’ve had some luck. But in this country, I still believe you’re rewarded for hard work. That’s what strikes me about living and working in the United States… value is assigned to sustained effort. Persistence is recognized here and that’s quite amazing.

What was the experience of starting a firm in a country in which you didn’t grow up?

When we started the firm in 2008, I had already been in the US for 14 years. I came right after high school. The US was my home at that point. Now I’m quite removed from the place I come from, in the sense of customs and business… it’s all very unfamiliar. I know my high school lingo in Turkish, but I don’t know how to operate there as an adult.

Does where you grew up have an influence on your work, or have you been removed from where you grew up for so long that it does not affect the work?

It’s hard to say. I’m sure it does in some deep psychological level. It’s been 25 years, and I’ve lived most of my life in the US now. But let’s unpack this. When I was in Turkey, I was a die-hard skateboarder, and I always wanted to go to California. I didn’t quite make it that far, but I found a partner who’s from California. I tried to come to the US during high school as well. I ended up in a really small town, which was very depressing. At that moment, I didn’t want to stay, but it was very clear to me that my future would be in the US. But where I come from certainly influences me. Exposure to certain conditions present in Turkey during the time I lived there definitely influence how I look at the world today.

Do architects have the responsibility to engage global issues?

You can’t escape them. But I don’t think architecture as a discipline is responsible for solving the world’s problems. There are other issues that we are immediately engaged with, that are more disciplinary and, to us, more important, at least from the perspective of an architect. I’d like to draw the line between a citizen and an architect. We have our politics, we have our interests, we know where we stand in terms of the issues. In the last 10 to 15 years, there are always voices within the discipline which claim a broader reach and an urgency to deal with political issues. We’re more interested in central disciplinary questions that operate through aesthetics, which has its own political agency.

Your answer reminds me of something you said in your 2014 Architectural League of New York talk, when you claimed that architecture should be separate from politics. You said that “architecture is not contingent, it develops its logic internally and grows from disciplinary concerns.” Can you elaborate on that and share how this belief affects your work?

The relationship between architecture and politics is intensifying, but we have remained focused on issues internal to our discipline as a way to ensure its continual evolution. For us, it’s most interesting to talk to other architects about architecture… to have deep discussions and debates about the pertinent and persistent architectural topics. Of course, architecture performs on a broader cultural platform once it’s out in the world, but we believe that we have a responsibility to imagine that we can use our knowledge and tools to create new worlds rather than simply reflect and accommodate the one in which we live.

In many of your projects, there is a continuous translation between objects, drawings, and buildings. Where does this interest come from and how does it ultimately affect your work?

Michael and I are stuck in-between architectural generations, which is simply a result of what was happening in architecture culture when we graduated from Princeton. We’re close friends and colleagues with the generation of architects above us—let’s call them digital formalists or the affect and sensation generation who focused on digital modeling, digital fabrication, and rendering—and the generation of architects below us, who are interested in things like figure, graphic expediency, and engagement, and who more commonly use physical models and collage. We’re interested in the routines and techniques of both cohorts. When we completed graduate school, the digital project was winding down as it pertains to experimentation in an academic environment. Michael and I were never directly a part of the authorship of that project. We never rejected it, but we also weren’t looking to dismantle it. We quickly realized that we were interested in engaging multiple contemporary mediums and modes of representation. We were operating through sketching, physical modeling, digital fabrication, lecturing, teaching, writing, etc. Our projects are intellectual pursuits as much as they are design speculations, and they are developed through and across each of those modes of operation. The combination of and translation between drawings, objects, and buildings is a way for us to combine unique mediums through which our aesthetic ideas mature.

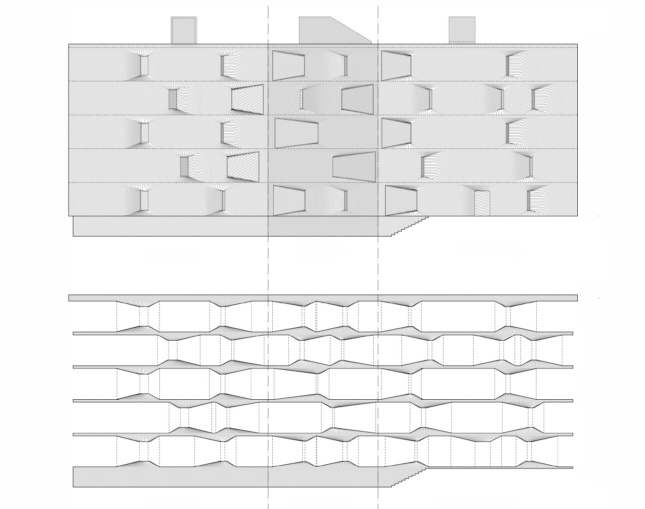

Can you talk about this approach to design in relation to your most recent project, DL 1310? How does the building embody conceptual studies that may have first appeared in drawings or objects?

It’s important to recognize that we evaluate all mediums individually. Throughout the development of DL 1310, drawings did things for us that objects could not, and vice versa. Equally important to note is that a drawing of the project by itself doesn’t necessarily capture the entire idea of a project, nor does a model, nor does the building. Cumulatively, these three outputs are the project. In fact, I would argue that as much as we love to build, the building is a form of representation with the very least amount of freedom in terms of articulating the architectural idea. This is because the building must account for more than a drawing or a model… concern for cost, financing institutions, contractors, subcontractors—these things add more complexity. We don’t think about these complexities in relation to compromise, but we do recognize the addition of necessary forces beyond our control that claim partial authorship over the project. In DL 1310, the building is inspired by a range of drawings and objects we’ve produced over the years in addition to the ones produced for that project. It goes back to an answer I gave earlier. All of our projects, including DL 1310, are part of a body of work with an interconnected and evolving aesthetic sensibility.

Regarding clients, who commissioned DL 1310? How did your relationship with the client impact the result?

The project is a collaboration between our office and Michan Architecture. Michan Architecture is an office based in Mexico City that is led by a former student of mine, Isaac Michan Daniel. We kept in touch after he graduated and moved back to Mexico, where his father owns a development company and serves as a collaborator. He called us one day a few years ago and asked us if we’d like to collaborate on a small housing project. That’s how it all started. It’s a relationship that developed through teaching that became a friendship and now a collaboration.

How does the office operate now? How many people do you employ?

Right now, it’s just me, because Michael is in Rome. Well, today he’s in London, but he is away all year at the American Academy in Rome. What’s interesting is that I’ve seen him more frequently this fall than I last fall when we were both in New York. Our teaching schedules don’t typically align so we’re always communicating over the phone and through email. So, it’s actually not different this year with him living in Italy. We’re currently working on a competition and our shared comments are made on the internet. This is the reality of practice today, regardless of whether your office is distributed or operating in one place. That’s how we’re managing projects right now. During the winter months, we rarely have anybody else in the office with us. In summer, we try to grow to four or six people for more intense production outside of the academic calendar. With a few exceptions, almost all of our projects have been completed during the summer months.

What’s been the most rewarding moment in your practice thus far?

The office is a place where I can go and explore ideas freely without the pressure of economic performance. Teaching affords us the opportunity to approach practice in this way. The space academia created for the practice is thrilling. It’s an incredible luxury. To have time to think about issues that interest us and to speculate on the way in which they become architectural… that’s the biggest reward. It’s incredible for Michael and me to have time to spend working on things that we love. For architecture, that’s incredibly important. If you’re working on a project that you’re not interested in, you’re not likely to do a good job. We really enjoy the day to day activities of the office. Because of the way in which we are able to practice, we remain excited and optimistic about the future and our ability to make meaningful contributions to the world through design.