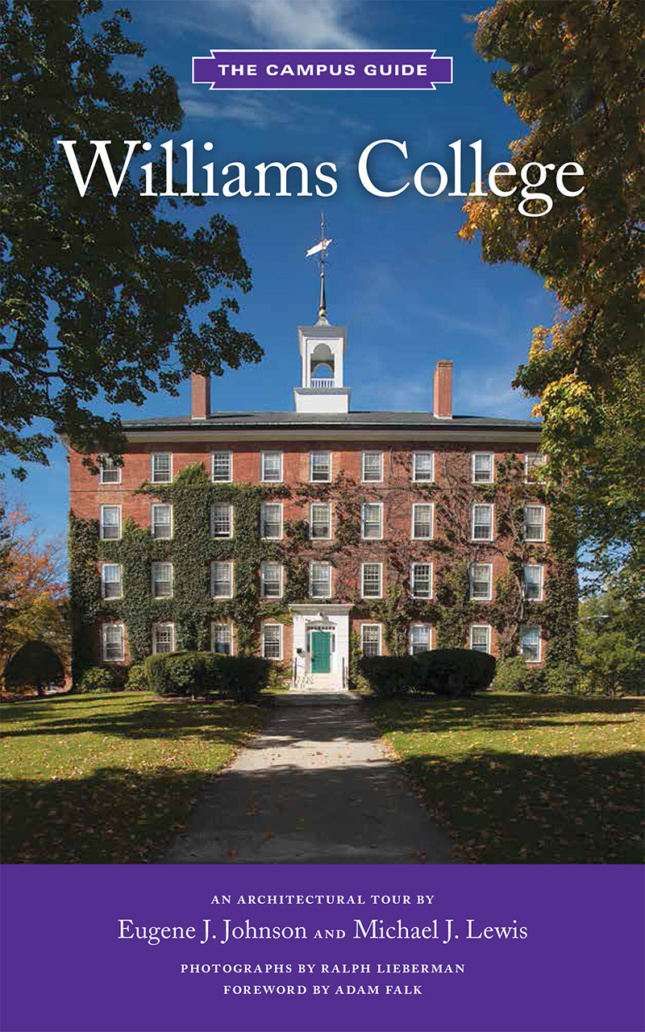

Williams College: The Campus Guide

By Eugene J. Johnson and Michael J. Lewis, photographs by Ralph Lieberman

Published by Princeton Architectural Press

MSRP $37.50

Williams College: The Campus Guide is more than a tour of the distinguished liberal arts college in far northwestern Massachusetts. It is rather a scholarly history and informed analysis of the school’s buildings and their role in shaping the visual identity of a hitherto architecturally undocumented place.

Williams is the 32nd volume in Princeton Architectural Press’s Campus Guide series, a twenty-year run that began with the University of Virginia in 1999. These handsome handbooks have enlarged our knowledge of collegiate design at some of the more notable American campuses. The quality, alas, varies from title to title. Some appear to be glorified brochures, while the Williams one is a major contribution to the literature.

What makes this guide exceptional is that the authors and the photographer are respected architectural historians with decades of teaching experience at Williams. More important, Eugene J. Johnson and Michael J. Lewis insisted that the college give them complete freedom in their opinions and observations. (I declined to do the series guide for my alma mater, as it was apparent that my college wanted total editorial control, and that their goal for the book was more public relations than scholarship.)

The Williams authors had additional hurdles. For much of its two-hundred-year history, the school was small, isolated, and not well endowed. Until women were admitted in the 1970s, raising both enrollment and intellectual rigor, the college was home to white prepsters, a place where the fraternity brothers “inhabited the kinds of architecture to which their parents had accustomed them.” Stacked up against architectural powerhouses such as Princeton, Yale, and MIT, Williams’ chroniclers Johnson and Lewis proffer a lot of fascinating history and background that enlivens the discussions of brick and mortar.

The early physical presence of Williams was Yankee utilitarian. Starting in the mid-19th century, a notable grab bag of Victorian designers worked here, including Gervase Wheeler, Thomas Tefft, Richard Upjohn, Henry J, Hardenbergh, and J. C. Cady. Much of the design was haphazard, depending upon donor whims. The Olmsted Brothers drew up Williams’ first campus plan in 1902.

Tastes tended to the safely conservative through the 1950s. Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, architects of the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, designed a student center in the default campus style, Colonial Revival.

Yet, college president Harry Garfield hired Ralph Adams Cram, the brilliant campus designer who shaped Princeton into an architectural masterpiece. The great Gothicist felt that his interpretation of English Georgian was more appropriate to the New England school. As always, Cram demonstrated a mastery of proportion, materials, and appearance. His Freshman Quadrangle is singled out as “the loveliest passage of the entire Williams campus.”

Despite hosting an avant-garde art department–a famous incubator of architectural historians and museum directors—Williams did not get a Functional Modern building until the 1960s. The Architects Collaborative (TAC) was hired to craft a campus plan, while the college awarded an honorary doctorate to TAC founder Walter Gropius. Jumping somewhat timidly into the Modern era, Williams secured successful dormitory complexes by Benjamin Thompson and Mitchell-Giurgola and a dining hall by Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott, along with a dreadful library by Harry Weese.

In the 1970s Charles Moore extended the art museum. This was “an adventurous move for a college that had traditionally gone with competent professionals rather than architects on the cutting edge.” Due to strained college finances, Moore paid for what he called “Ironic columns” on the museum’s exterior, itself a riff on the architect’s concurrent Piazza d’Italia in New Orleans.

Despite commissioning such leading names, building at Williams remained ad hoc and episodic. A stunning library by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson is offset by William Rawn’s Center for Theatre and Dance, a gratuitous “expression of architectural ego,” the placement of which truncated a bold axial plan by Denise Scott Brown. Missed opportunities include an unrealized Steven Holl art building and a somewhat flaccid student center by James Stewart Polshek. The combination Chandigarh-and-New-England-styled resort hotel was “chosen from a long list of distinguished firms,” including Venturi Scott Brown and the Helsinki uber-Modernists Heikkinen + Komonen.

Mikko Heikkinen and Markku Komonen were interviewed, along with Alvaro Siza, Tadao Ando, and another architect (the names were never revealed to the public) about adding a wing to the Clark Art Institute. Ando’s building is called “a disappointment,” primarily for its planning, and the wall of donor names, “sized according to the amplitude of their donations,” draws particular scorn.

This biography of Williams College and its architecture is told as a family epic: A complicated life, full of intrigue, might-have-beens, and triumphs. Or as Adam Falk, president from 2010 to 2017, writes in a foreword, the guide is “historically insightful, compulsively readable, visually stunning, and infused with a healthy dose of irreverence.”