Agnes Denes’s watershed retrospective at The Shed, the sliding art hall at New York’s Hudson Yards, Absolutes and Intermediates (open through March 22), feels at times audaciously oracular. With its global environmental themes, conceptual graphs of the totality of human knowledge, and exaggerated post-human scale drawings, the exhibition speaks to a millenarianism powerfully present today among anyone paying attention. Yet, much of it she conceived a half-century ago. At times, it makes Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion domes and the previous heroic gestures of land art look like frivolous child’s play.

“I asked her once how she knew in the early ’60s what we know now about this place, where in the early ’60s you didn’t have phrases like climate change,” said curator Emma Enderby, who organized the show. “She just said that it was there. Scientists were talking about it. You just had to have your ears open and your tentacles out. You had to be reading the texts and reading between the lines.”

Before joining The Shed as a curator, Enderby worked at Public Art Fund, where she became familiar with Denes through her landmark Wheatfield—A Confrontation (1982), which the organization sponsored. Back in 1982, Denes planted two acres on landfill dug up from the World Trade Center while the site sat empty waiting to be developed into Battery Park City, arguably her most famous work. Enderby suggested a retrospective, along with the idea of commissioning unrealized pieces, in line with The Shed’s mission to support original cross-disciplinary work. The work is well organized and emphasized thanks to the work of the New York-based New Affiliates, who designed the exhibition.

Photographs of Wheatfield staged by a TIME Magazine photographer show Denes standing Moses-like with a staff in the field of golden wheat, the gray towers of Wall Street on the horizon, contrasting the subduing, objectified, and commodification of the built environment with an image of resurgent nature. The figure of a woman projected as a life-giving force alongside one of the earliest human technologies, agriculture, hinted at a possible regeneration of incessant urban verticality and sprawl.

“It was insane. It was impossible,” Denes wrote. “But it would draw people’s attention to having to rethink their priorities and realize that unless human values were reassessed, the quality of life, even life itself, was in danger.”

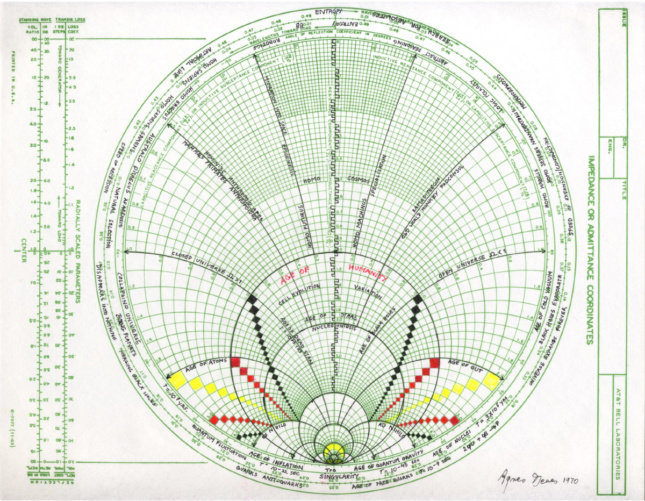

The exhibition sprawls through two floors of The Shed’s double-height galleries, taking its title from a radically-scaled parametric chart Denes plotted on a sheet of AT&T Bell Labs graph paper in 1970. Absolutes and Intermediates visualizes nothing less than the history and future of the universe, from its formation to its disappearance into nothing, sweeping through the emergence of human life, the development of abstract reasoning, the creation of superintelligent machines and artificial life forms, and the evolution of a future species of homo sapiens.

Expansive, minutely detailed drawings of Denes’s grand alternative systems and condensations of knowledge are displayed in long vitrines—some of them longer than 20 feet—beside study models and video interviews that show Denes as much a thinker as a visual artist.

Another uncanny early piece from 1970, Matrix of Knowledge, predicts information overload in ways that are halfway too optimistic, halfway right on the mark. Charted using dialectic triangulation, in which Denes represents interconnected fields of knowledge as intersections of that construct larger geometric structures, she wrote that the sum of accumulated information doubles every ten years, more than the mind can handle. In the future systems will have to be set up to preselect and reduce incoming data, leading to loss of freedom.

“Mass media is already making choices for us,” she wrote at the time, “a[nd] specialization is also leading in that direction by trapping valuable data within each specialty where it remains undigested, hindering accurate deductions and combination as the flow of communication is blocked.”

A maximalist ecological intervention conceived in 1982, Tree Mountain-A Living Time Capsule—11,000 Trees, 11,000 People, 400 Years is breathtaking in its ambition and gets a dedicated display room at The Shed. Commissioned on the occasion of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and realized by 1996, 11,000 trees were planted in a gravel pit in Ylöjärvi, Finland, that was being reclaimed from environmental destruction. Each tree was assigned a dedicated custodian, along with a certificate naming its owner. Planted in a swirling pyramidal pattern, Tree Mountain would take on its full meaning over the course of centuries, Denes wrote, changing from a shrine to a decadent era to a monument of a great civilization to benefit future generations.

The entire second floor is devoted to a large number of Denes’s conceptual pyramidal drawings, along with three special commissions created for the show. The pyramids are largely thought experiments expressed as drawings on a crazy scale, such as her iteration of Pascal’s Triangle, no. 3 (1974), which extends halfway across the gargantuan Shed gallery, displayed in a glass case, all drawn by hand in painstaking detail. Others use dots, thin lines, and stick figures to sketch out eccentric forms—probability, a flying fish, silk, reflection, a flexible space station—creating pyramids in which slight individual variations result in reverberating distortions in the whole.

The gallery commissioned a version of the probability pyramid, Model for Probability Pyramid—Study for Crystal Pyramid (2019) and built it from nearly 6,000 3D-printed corn-based bricks, taking advantage of the venue’s unusual ceiling height and technical capacity. Illuminated from the inside, the crystalline structure stretches to 30-feet-by-22.5-feet at its base and reaches 17 feet in height. As originally conceived, the pyramid would be constructed of 100,000 glass blocks, rivaling the ancient pyramids and carrying mathematical information into the future.

Another special commission was a translucent, teardrop-shaped object, also lit from inside, and hovering mid-air. A custom electromagnetic circuit in the base and a magnet within the sculpture suspends the teardrop as if by magic. It’s a model for a monumental architectural structure, a floating city conceived in 1984 as a part of a series of organic forms. The structures reference back to 4000 B.C Egyptian pyramids and were created for a future in which their inhabitants live in space or self-contained floating environments. They’re intended as mandalas that define benevolent destinies: The structures “break loose from the tyranny of being built,” Denes wrote, becoming “flexible to take on dynamic forms of their own choosing. At this point they decide to fend for themselves and create their own destiny.”

The other special project, Model for a Forest for New York (2014— ), is a much more recent one: A plan to plant 100,000 trees in a form that looks like a flower from the sky on a 120-acre landfill in Edgemere, Queens, with support from the Rockaway Waterfront Alliance. The forest’s conception is also more straightforwardly contemporary, appealing to public health concerns, as it would address asthma problems in the adjacent neighborhood, remove carbon dioxide from the air, and help clean the groundwater. That makes the project somewhat more prosaic, and in a way disappointing—in the same manner as a waterfront berm with a park on top, which suggests the greater truth of her aesthetic project.

Well-known ecological artists like Peter Fend have complained for ages that artists are not taken seriously when proposing environmental interventions because they are not trained engineers, and the resultant projects are often wildly out of scale and untested. But with the world as we now know it is coming to an end, be it the current political order or via the climate crisis, Denes’s visionary planetary-scale retorts have a fitting rejoinder: Absolutes and Intermediates suggests the potential of aesthetic imagination—not just quantitative trading and tech engineers—to regenerate it anew.