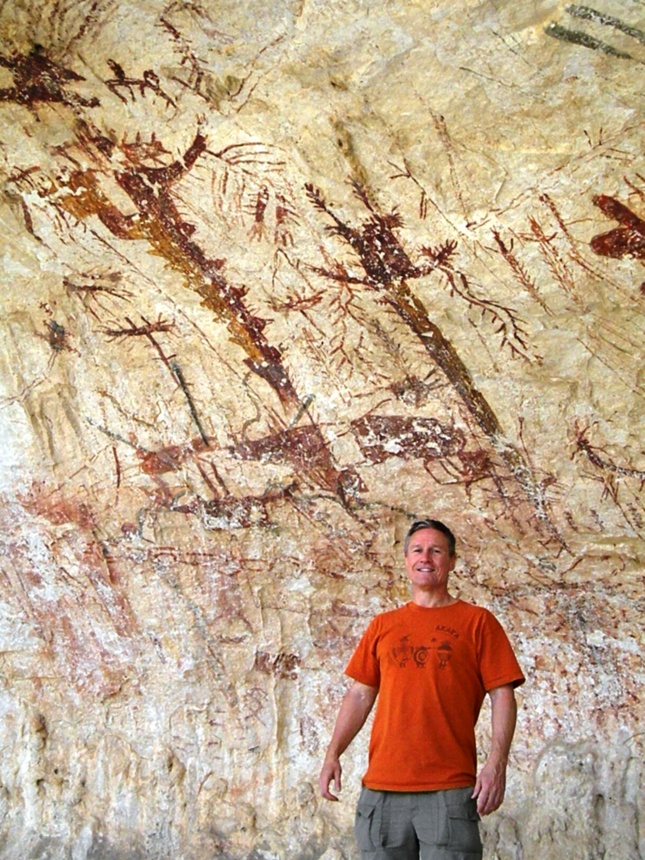

Steven J. Waller practices archaeoacoustics, an emergent subdiscipline of archaeology that studies the sonic dimension of archaeological sites, including a location’s capacity to produce resonance. Waller’s research focuses on rock art. He was the first to theorize that echo, when interpreted by ancient people as spirit beings living in rock, was a motivational factor in rock art image placement. In preceding a science of acoustics, rock art, in Waller’s conception, begins to function as a tool for phonetic transcription or proto-recording, pointing toward the ability of materials to talk back to us—if only we listen.

Emma McCormick-Goodhart: What are the prevalent architectonic and sonic characteristics of rock art sites in the American Southwest?

Steven J. Waller: Much of the rock art in the Southwest is sited in canyons and on cliff faces, rather than in deep caves. A canyon is almost like a cave without a roof on it. Sound still bounces around; it’s just that in deep caves, it’s much more reverberant or resonant. Reverberation is like a thunderous sound, whereas in shallow shelters—canyons or cliff faces—it’s more like a distinct echo that speaks back to you, sometimes with multiple repeats. Shelters are interesting, because they can act like a parabolic reflector, just as antennae dishes focus sound and help to magnify it. There’s a place in Chaco Canyon [in northwestern New Mexico] called Tse’Biinaholts’a Yałti (Curved Rock That Speaks). An artificial mound was built at the focal point of this curved cliff face, and you can actually get an echo that’s louder than the original sound, because it focuses it. There’s a legend associated with a spirit being that’s in the rock.

In fact, there’s a whole mythology about portals that open up into a spirit world. Sound reflection helps to give that illusion. It’s like when you look in the mirror, you look in the mirror—and sound reflection gives that same illusion of depth. Even though you can see the rockface, what you’re hearing is depth, as if there’s something beyond there: a chamber or something, where spirits are living. It’s an interesting illusion of space. In the Great Gallery at Horseshoe Canyon [in northern Utah], for instance, it’s like the paintings speak back to you.

Sound reflection, as a general phenomenon, would have been inexplicable to ancient people—whether it was a distinct repeat, or a reverberation that blurs together like thunder—because they didn’t know about sound waves. Instead, they had a supernatural explanation for this phenomenon. Hearing it as communication with the spirit world, they sought these spirits deep in caves or way up on cliffs, where sound appears to come from.

How did you “hear your way” into this theory?

I don’t think that it was a Flintstone kind of sound system for their music; I think that it was spiritual. I made my discovery, by accident, at the cave of Bédeilhac, in France. I was standing outside of the cave, waiting for my wife to get a sweater from the car, and I asked myself, if I were a caveman, why would I go deep inside the cave? Why would I only decorate certain chambers? Why would I only depict certain things—and what was taking her so long? I yelled, “Hey, Pat,” and the cave spoke back. My subconscious heard that echo not as an echo, but as a voice speaking back—and I instantly remembered learning about the legends of echo spirits that live in the rock. My subconscious realized ancient people would’ve heard it like an echo spirit calling back to them, calling them into the cave. That was in 1986, and I’ve been going to as many caves and canyons as I can ever since to test my hypothesis about the correspondence of sound and rock art. The more places I go to, the more I hear it.

You argue for the preservation of soundscapes at sites of rock art. Can you elaborate what’s at stake in facsimile production?

It’s a natural offshoot of my theory: the realization that a rock art site is not simply the panel of images, but also the experience of the sound environment around it, which is, I think, what inspired the rock art. There’s effort dedicated to documenting and “preserving” rock art, which to me means keeping the original, but to a lot of people means making copies. They’ll spend months recording every stroke, yet they make no effort to document or study the sound. I think that if they’re making a facsimile or replica and they want people to have a realistic experience, it has to include sound—it has to be audiovisual—or it’s going to be misleading. Lascaux II is completely misleading—it might as well be your living room. The sound is dead. They gave no thought to acoustics at all, even though millions were spent reproducing the shape of the cave to the centimeter, and art to the brushstroke. It also doesn’t necessarily have to be a physical replica of the cave; this can be accomplished with virtual reality.

What might explain this recurring sonic omission?

I think that it’s twofold, at least. One is that we, as modern people, know about sound waves and reflections. We know what an echo is, so it’s trivialized. It’s such a contrast to how echoes were viewed in the past as spiritual phenomena, revered to the point of worship. There are legends around seeking echo, like the Acoma migration story. They would go to places and test for echo, and if the echo was no good, then they would move on. The legend describes a place just to the east of Acoma, where they found the perfect echo. The land area of the Acoma tribe has the Petroglyph National Monument [outside Albuquerque, New Mexico] at its eastern boundary, and it is one of the strongest echoes I’ve ever recorded. There’s also another myth: “The white man calls it an echo; these are witches that live in snakeskin and inhabit sheep. That’s where the echo spirit lives.” Some legends don’t call it an echo, but a “talking rock.”

The other thing is that the very name of the thing that we’re studying is rock art, so the attention is focused on the “art,” or the visual. I think it’s more interactive and audiovisual, because of the evidence I’ve collected showing the correspondence between locations that were selected and their sound reflective intensity—so it seems like they purposely chose places with the best echo and reverberation. I don’t think that the art was an afterthought, but an auxiliary part of the ritual.

You’ve written about the percussivity of stone tool production as another source for interpretative “mishearing.”

When you’re flint knapping and making stone tools, those percussion noises—when they echo back—sound like hoofbeats. That’s why certain engravings are of hooved animals. They might’ve even purposefully chosen places like that to make their stone tools, thinking that it might endow tools with magical qualities reinforced by spirits. You could also speculate that that’s how they discovered making tools; that they were banging rocks together to make echoes, and some of them happened to break. Some people have been looking at the tonal quality of some of these blades. It makes you wonder how much sound impact was important for stone toolmaking.

Sound is still physically measurable in rock art sites. Sound doesn’t fossilize, per se, but might it be useful to think of sound as a living fossil layer—a form of what UNESCO would term “intangible heritage”?

That’s an interesting way of looking at it, because it’s not that the sound itself can still be heard, but that the structure of the place—the characteristics of the rock, and the shape—still produces the same phenomenon as it did then. Any effects of erosion add statistical noise or statistical uncertainty, but I think that most of these places are spatially similar enough now to how they were in the past that you can figure the sound is going to be quite similar. You’re not hearing the same airwaves as our ancestors, but the same acoustic response. I try to apply my scientific methodology and hypothesis testing as a basis for arguing for the conservation of soundscapes in order to study rock art not just with our eyes, but with our ears, too.