The automobile—a long-time fetish object of architects, the car is arguably the object that defines the 20th Century and one that has perhaps sent us crashing us into the 21st. The development of the car was once fuelled by optimism, able to set people free to go where they wanted, when they wanted. Today, however, its image has been tainted by its contribution to the climate crisis. The car is both personal and global, shaping lives, cities and nations, and it is the subject of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s (V&A) latest exhibition: Cars: Accelerating the Modern World.

There’s no Lamborghini Countach, no Citroen DS or Aston Martin DB5 here, this isn’t that kind of show. Cars is a critique of the automobile and its impact. Expect instead to find posters about workers rights relating to Fordist assembly lines, maps tracking global oil production, the world’s first commercial car designed using wind tunnel testing (the Tatra 77), and Graham, the viral, life-sized latex figurine born from the Transport Accident Commission of Australia that shows how humans could evolve to survive a car crash.

Tucking the exhibition into the new AL_A-designed Sainsbury Gallery at the V&A in London, curators Brendan Cormier and Lizzie Bisley have, through a welcome variety of mediums, given audiences a thrilling ride through the history of the car that’s full of unexpected turns.

With regards to architecture, we’re given Prussian-American architect Albert Khan’s plans for the Henry Ford’s Highland Park plant, the place where assembly lines were first used for industrial production. Next to it is a model of Italian architect Giacomo Mattè-Trucco’s Fiat Lingotto factory in Turin, complete with rooftop test track. But nearby is something more sinister—a letter from a Highland Park factory worker’s wife to Mr Ford. “The chain system you have is a slave driver! My God!” it reads, detailing the perils of the factory conditions.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Ford was a control freak. In 1926 he purchased land in Amazon Rainforest to produce his own rubber. Brazilian workers were banned from smoking, drinking alcohol and playing football, while American customs such as square-dancing in community halls and working in the sun, as well as hamburgers in the canteen, were introduced. The workers revolted and “Fordlandia”, as it was known, was abandoned in 1945.

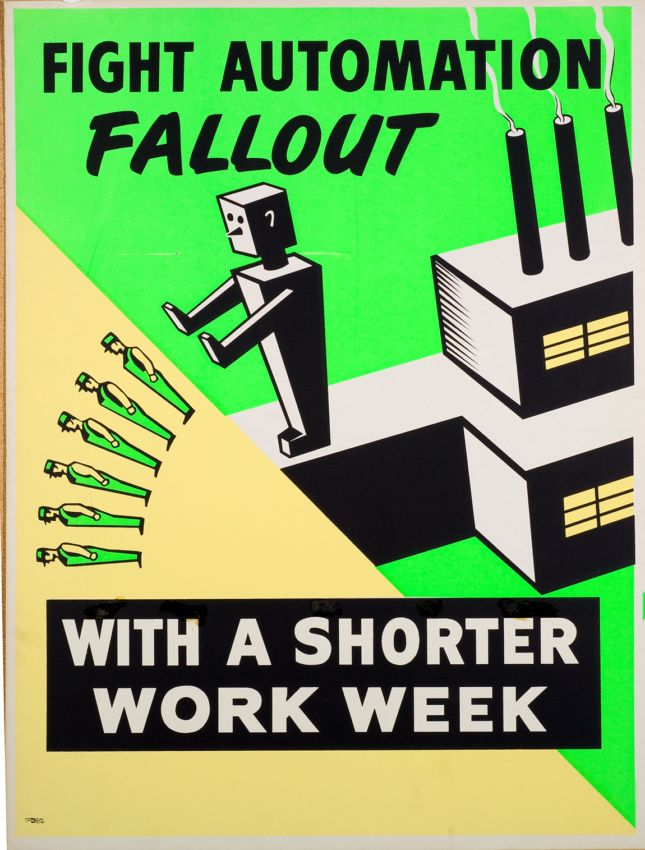

Factory revolts and angry letters to bosses may be fewer and far between now, particularly as machines usurp humans in factory line production. A lengthy and eerily slow panning projection of the inside of the BMW Group Plant in Munich duly demonstrates this. Here machines do the heavy lifting while humans keep watch.

Cars also delves into the wider spatial implications of the automobile. Le Corbusier, who was as obsessed with the car as any architect (maybe more), designed the Maison Citröhan (1922)—named in the car manufacturer’s honor—to be as efficient as the car. Tire manufacturer Michelin, meanwhile, carried out an exhaustive photographic study of dangerous roads in America in the 1930s, highlighting the need for urgent improvement, and an array of photos from this shows just how poor America’s roads once were. Missing, however, is Frank Lloyd Wright’s conception of the garage. The car’s impact on suburbs, roadside architecture (notably the work of Denise Scott-Brown), along with highways and freeways and drive-in cinemas is also amiss, but these do all feature in the exhibition’s accompanying book, which has been beautifully produced.

“In the end we ran out of space,” Cormier told AN. More important to the curators was to expose the rush for oil extraction the car created and the devastating effect this is having on the environment, which is understandable.

Throughout the exhibition, visitors are continually exposed to visions of a future which will never exist. One example: adverts and sci-fi films from 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s show many men in many cars, but none are stuck in traffic. By analyzing the automobile through the rear-view-mirror, Cars highlights how the car and modernity have failed to deliver on many promises. That hasn’t stopped the industry, though. In the last room is ‘Pop.Up Next’, a concept from Italdesign which combines an electric car and a drone that is able to clip onto the pod-like vehicle—or rather, another attempt at a flying car, a never-realized fantasy of old which, like its predecessors, may be destined to forever belong in a museum.

Cars: Accelerating the Modern World runs through 19 April 2020.