Hare & Hare, Landscape Architects and City Planners

Carol Grove and Cydney Millstein

University of Georgia Press in association with Library of American Landscape History

List price: $39.95; 264 pages

Cemeteries are like cities. They need streets that efficiently accommodate traffic flow, harmonious neighborhoods of related structures, visual landmarks and vistas, and a sense of place that will attract not only its permanent residents but also visitors. Sidney J. Hare (1860–1938) was one of America’s most influential designers of such landscapes. “On a national level, Sid’s foremost contribution was his participation in the ideological and physical shaping of a new type of cemetery, one fit for the twentieth century,” write Carol Grove and Cydney Millstein in their book, Hare & Hare Landscape Architects and City Planners.

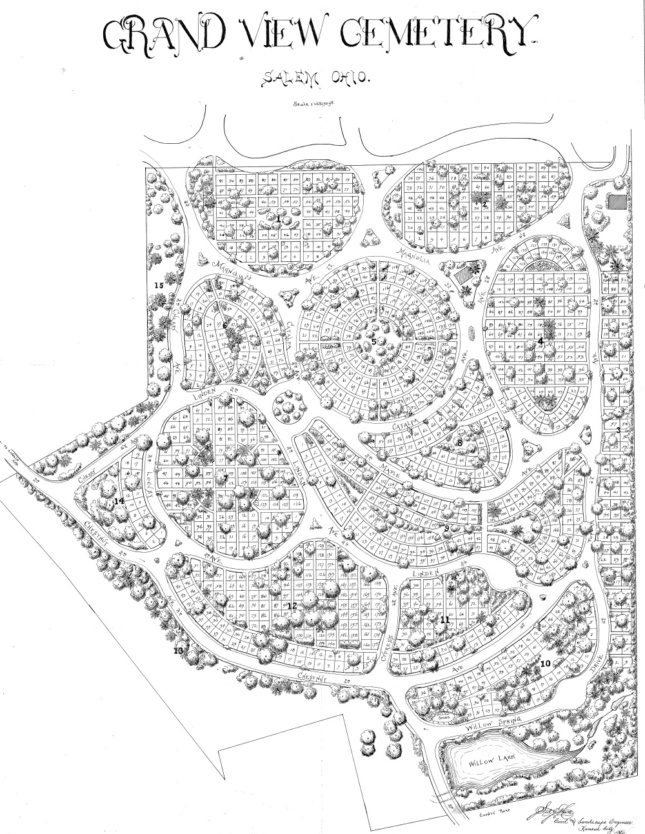

What had once been spooky, gloomy, often remotely sited plots of land well outside the city limits for the dead, suddenly became, through the work of Hare and his son, S. Herbert Hare (1888–1960), in-town locales that were very much alive. The father-son team of landscape architects, based in Kansas City, designed fifty-four cemeteries throughout the country and one in Costa Rica—among them, Forest Hill in Kansas City, where they would both eventually be buried. In Monongahela, Pennsylvania, and Grandview in Salem, Ohio, which would forever change the way the dead and the living interact. The team fashioned cities of the dead that incorporated macadam-paved roads that honored the natural topographies, introduced engaging architectural elements, along with lakes and plant features, and chose foliage for the ways they would change throughout the seasons. A kind of design mantra evolved for them: More nature and less marble and stone.

The elder Hare “understood more than aesthetics,” the authors recount in this first-ever dual biography of the designers, for he was “grounded [too] in the technical aspects of dealing with nature.” Quoting Hare directly, the authors write that he considered the best cemetery to be a “botanical garden, bird sanctuary, and arboretum.”

The book proves that some of the best-recognized and most prized city planning designs are often ones whose makers go uncredited. “It was not until the formation of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1899 and Harvard and MIT’s offering courses geared toward future practitioners the next year that landscape architecture began to coalesce as a profession,” write Grove, a professor of art history and archaeology at the University of Missouri, and Millstein, founder and principal of the Architectural and Historical Research in Kansas City. This record of the Hares’ lives and works reinforces the notion that the discipline of landscape architecture is “the fourth fine art after architecture, painting, and sculpture.”

The moment the elder Hare enlisted his son to join the firm he established in Kansas City’s Gumbel Building in 1910, the two embarked on making some of the most resonant landscapes in America. One of the great American places is Kansas City’s Country Club District, for which Hare & Hare would plan some 2500 acres over a forty-year period. They would incorporate extant pasture land and wood into some of the residential neighborhoods, including Mission Hills, defined by narrow, sinuous roadways, interior parks or “parklets”, as they called them, and carefully chose flowering shrubs and sculptural trees. So obsessed was the father-son team during their work on the complex, which they began in 1913 with the developer, J.C. Nichols, that no element was too small to be accounted for—weathervanes, bridges, the fonts on the signage, the placement of public artworks, the locales for campfire sites and bridle paths. Grove and Millstein expertly detail the process for this city planning project, recounting that the Hares made more than two hundred finished drawings, apart from those they executed for some of their many individual residential commissions within the district. “Transformed by Hare & Hare’s plan—praised as beautiful, thoughtful, and original—Mission Hills was perhaps the finest neighborhood executed for Nichols,” conclude the authors.

No landscape, no matter how seemingly topographically challenged, couldn’t be tamed and transformed by Hare & Hare. For their many works in Houston, for instance, the elder Hare’s vision for the new residential neighborhood of Forest Hill embraced as one of its defining scenic attributes what many would have considered its biggest natural obstacle—a swampy, sinuous bayou. Making that watery source one of its focal points was a revolutionary idea in its day. He and his son decided to depart from the strict street grid of nearby downtown Houston and instead fashion a series of roadways that radiated in arcs, outward like a giant fan. Meanwhile, their work in planning the city’s exclusive residential neighborhood known as River Oaks—some 2000 acres of land—endures. As the authors point out, “Fifty years after its inception, the architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable condemned 1970s Houston, but noted River Oaks’ exceptional planning.”

Other notable projects of theirs documented by the authors include Houston’s Hermann Park, on which the Hares worked for more than twenty-five years, the expansive grounds of Tulsa’s Villa Philbrook (now open to the public as the Philbrook Museum of Art), the city of Longview, Washington, the Lake of the Ozarks, and parks in Fort Worth, Dallas, Joplin, Missouri, and elsewhere. Ultimately, upon the younger Hare’s death in 1960, the firm could list some four thousand projects in more than thirty states, Canada, and Costa Rica.

As Robin Karson, executive director of the Library of American Landscape History (LALH) points out in her preface, the book “covers so much formerly uncharted territory in the history of American landscape design.” Indeed, LALH’s ongoing mission is to keep laying the often ignored historical groundwork for the discipline of landscape architecture. Even though the book immerses readers at times in the thick brambles of city bureaucracies and office politics through which the designers had to hack their way, the personalities of the two men emerge, so much so that the book functions, too, as a revealing biography of them. We feel them in action. Of Herbert, the authors state, “…he recognized that good design was achieved both over the drafting board and in the field, not by one or the other.”

“Sid and Herbert believed that good landscape architecture was both a science and an art,” the authors state. “Although they emphasized the practical, functional role of their profession, they firmly believed that if a city for a garden ‘is not to be a work of art, then it would be best not to build it.’”

We are grateful the Hares designed it and built it. And readers should be grateful this book was published to keep their accomplishments acknowledged and flourishing.