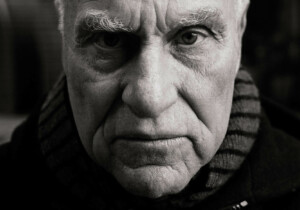

Cristiano Toraldo di Francia sadly passed away on July 30. Cofounder, along with Adolfo Natalini, of the Florentine Radical design and architecture group Superstudio, Cristiano was the kind of person who was incredibly open-minded, shared a sharp sense of humor, and professed a deep love for humanity. While accolades spread across the internet following news of his passing, there was a lot to Cristiano that didn’t make it into these postings, tributes, and memorials. What might have been most lacking in all these accounts was the way he shrugged off fame and shunned formality. Yet he never wasted a moment, had infinite stamina, and to stick by him you needed to react fast and move quickly.

Cristiano was a perceptive and ever-present photographer, and it is thanks to him that so many historical moments during their superlative adventure were captured for posterity. When I asked him about how he got into photography, he spoke about his father, Giuliano, who was a renowned physicist, recounting an odd story about how he was introduced to his first photo-camera.

As Cristiano told me, in an interview at his house in Filottrano back in 2005, his father “…designed lenses for Ducati, at that time they made electronics—now they´re making motorcycles. They made cameras, radios. And they made a micro-camera, which anticipated the cameras of today, instead of the normal 35 mm film –24x36mm, they were using 24x18mm film, so it was fantastic. Italy was poor at the time, everything had to be reduced!

Cristiano couldn’t help make a quip about the States, and while proudly acknowledging that Italian technology was inventing incredible things that were “almost too advanced for their time,” in America “everything was big—big cameras, big cars. But that camera was a jewel… Just to say that since I was a child I was initiated to the mysteries of photography—the images coming out of the acids, of the paper.”

Probing further, I asked Cristiano what his relationship was to the burgeoning Florentine fashion industry in the early sixties when he was a professional photographer.

“I was making family portraits at the time to raise money. In Florence, there is a big tradition around the Alinari family that besides all the city portraits,” now in the Alinari Archive in Florence, “they shot a lot of family portraits, but these were like paintings, all retouched, like Photoshop.

“They were perfect photographers- so this tradition was present. I was trying to do a very different kind of photography. I looked more to the American model. A journalistic kind of picture, Diane Arbus… Not so much Man Ray or the historical ones.

“I became quite successful at the time. All these noble mothers came to make photos in my studio. After a while, I was asked to do fashion photography, but after a while, Superstudio started and I quit. But of course, I had all the contacts and all the people- I was friends with Oliviero Toscani for example,” who would go on to make the controversial photographic campaigns for Bennetton. With his usual irony, Cristiano pointed out that he also worked as a fashion model, for the kind of magazines that were constantly referencing architecture.

It’s hard not to talk about the origins of the Italian Radical movement without getting into influences, of which there were many: “We started…” as Cristiano clarified in that same interview, “…on parallel levels, looking at Archigram, but even more we looked back at Dada and then to Pop-art that was bringing the Dada methods up to date. Fluxus—breaking boundaries and being completely interdisciplinary, fluctuating from one activity to the other. But on the other hand, Archigram had this political information as background—for which we could say maybe we were more idealistic than them. They were more pragmatic, more Anglo-Saxon.”

Dan Graham connected his generation to Rock and Roll, and given the times, it is clear that music played a considerable role for Cristiano. When I spoke to Cristiano about music when we met in December of 2002, he had this to say: “When I talk about the importance of music, we don’t deny having discovered a person like Bob Dylan, or the Beatles, it was a time when popular music reached great artistic levels, Laurie Anderson, the whole group of Fluxus, back then there was a system of self-propulsion, in every field…” What is critical in understanding Superstudio is precisely this level of mixing passions that the art and architecture curator Lara Vinca Masini referred to as “contaminations.” Cristiano stabbed at this point by bringing in Aldo Rossi: “Yes the work of Rossi and others was interesting, but it was always inside a discipline with few confrontations with the world that went much faster than their own reasoning.”

Getting back to the Florentine music scene, Cristiano credited his father with exposing him to experimental music when he was beginning university. In a conversation I had with him in 2005, Cristiano remarked: “My father was a scientist, and as a scientist he was traveling a lot and, in a way, disillusioned and relativistic. He was asked in 1963 to become president of the young contemporary music association. One of those members was Sylvano Bussotti,” a Florentine native, musical polyglot and noted dandy. “One was Giuseppe Chiari,” the atonal musician, close to John Cage and a member of Fluxus, “and the other was Pietro Grossi,” a Venetian electronic musician and composer living in Florence. “I remember they were making concerts of electronic music, and one concert was in the Conservatorio di Musica Cherubini which is a traditional music conservatory. And after 10 minutes of this music people went crazy.”

Evidently, for this generation of young architects living in Florence in the sixties, these were incredibly stimulating years. Superstudio detoured around the traditional tools of the architect, experimenting with alternative forms of expression and representation. When Emilio Ambasz showed up in Florence around 1971, scouting for ideas for the upcoming exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape for MoMA, the young curator was seeking out experimental “environments.” These would be full-scale prototypes for living, accompanied by films serving as animated captions. Yet I wanted to know just how Superstudio produced this project, what kind of technology was used to build this elaborate environment and how did they create their 12-minute film Supersurface.

The main backer for the environment was the manufacturer Print but they also had to procure other funders, due to the elevated expenses. According to Cristiano, they found the supplies they needed in Florence, the special reflective glass and the electronic components key to simulate alternating moods of day and night inside the environment. It took 15 days to manually assemble it before the show opened in New York on May 26th, 1972.

The movie was instead made during the winter of 1971- 72 and it was filmed in 36 mm. “I worked on that with Sandro Poli,” the Superstudio member officially present between 1970 and 1972, “we found the music, made the soundtrack, with the professional help of a guy who made advertising for TV (Marchi Producers), who had that mentality, and in fact, we wanted it to be projected as if it would be an advertisement for the Supersurface. The first part presents in a scientific way how the thing is done, and the second one tells how happy you will be living there.”

In fact, both making the environment and directing the animated film were very labor-intensive hands-on processes. I asked Cristiano what role the Italian manufacturers had in producing Superstudio’s concepts. Cristiano’s response was that these factories were mostly made up of artisans.

“That is why we managed to make a series of objects from very different things and from really different materials. Most of these objects are coming out of a kind of bricolage. The factory made almost nothing—we had to find artisans who did the different parts. The industry would just put the parts together. We were doing a kind of bricolage Cheap-scape—as Frank Gehry would say—for the industries.”

The Italian design industry seemed to work as an artisanal chain assembly. But what was still not clear, was why did these manufacturers get behind a group like Superstudio to make things that worked against the idea of mass consumption? Why would they sponsor designs that were against their best interests?

“We thought these objects we were making were a kind of trojan horses that coming from inside the system would produce criticism, which means creativity, which means refusal, or incredible love. They were objects of poetic reaction for the people. They were not mass-produced, they were in little series, multiples, like works of art.”

To this day I still think about Cristiano’s trojan horses, and his incredible love.