Following the release of an updated scheme for 550 Madison in December of last year, Snøhetta once again went in front of New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), this time for a Certificate of Appropriateness.

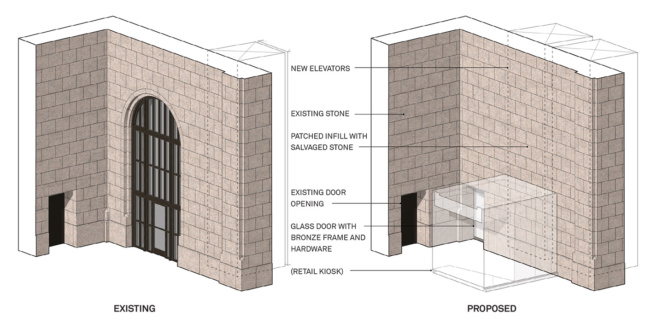

The changes to the postmodern, Philip Johnson and John Burgee–designed skyscraper (now a New York landmark) are much more modest than the Snøhetta design that sparked the ire of preservationists back in 2017. Under the revised plan presented to the LPC on January 15, only six percent of the 1984 AT&T Building’s original facade would be changed. That includes a new row of windows on the western side (the rear) of the tower’s base and infilling the two large arches to accommodate the new elevator shaft locations in the lobby and the relocated doors to the rear passage.

At the LPC meeting, Snøhetta, along with representatives of 550 Madison’s owners, Chelsfield America, Olayan America, and minority partner RXR Realty, described their design philosophy for the scheme: “Preserve and revitalize the landmarked tower, restore the original site design intent, improve on multiple alterations at the base, increase and enliven the public space.”

The glass-enclosure added to the building’s rear plaza in the 1994 renovation by Gwathmey Siegel Kaufman would be stripped and replaced with a lightweight and open-ended Y-shaped steel-and-glass canopy. The quarter-circle glass canopy and attached annex were original to Johnson and Burgee’s design, but enclosing the open-air walkway meant that catwalks and a ductwork system had to be installed to ventilate the space.

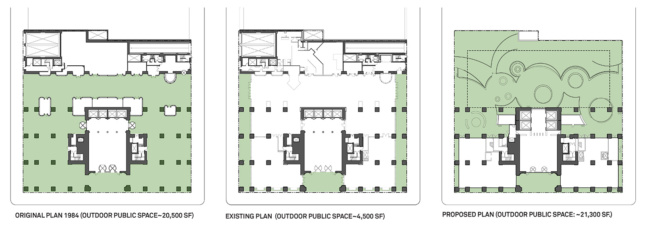

Snøhetta claimed that by removing the annex building and extending the canopy to the tower’s neighbor, along with opening the rear row of enclosed colonnades, the firm could increase the amount of available outdoor public space to 21,300 square feet from the current 4,500 square feet. That’s up from the original open-air breezeway scheme from 1984 as well, which only included 20,500 square feet—and that’s including the unenclosed colonnades that served as the building’s privately-owned public space (POPS). The new garden would be arranged according to a program that heavily invokes circles, a motif that, as Snøhetta noted, Johnson returned to again and again throughout his career.

At the building’s Madison Avenue–facing front entrance to the east, the design team elaborated on their plan to replace the heavily-mullioned windows added to enclose the flat arches by Gwathmey Siegel Kaufman. At the direction of Sony, which was headquartered in the building from 1992 to 2013, the columns were enclosed to create street-level retail spaces—something that AT&T fought against vehemently during the tower’s design process.

While 550 Madison’s ownership team won’t be opening up the colonnade POPS and transforming it into a public space again, they’ve instead proposed replacing the windows in the flat arches with much larger panes. The new windows, which would only be divided into a three-by-four grid with two-inch-thick bronzed mullions, would be set back five feet from the front of the arches, unlike the current windows, which sit flush with the sidewalk.

Public testimony presented before the commissioners was mixed but trended favorably. Representatives speaking on behalf of Robert A.M. Stern, Barry Bergdoll, Richard Rodgers, Signe Nielsen, Alan Ritchie (who worked on the original project with Philip Johnson in the 1970s), Claire Weisz and Mark Yoes, Elizabeth Diller, and others presented letters of support for the new proposal. Johnson Burgee wasn’t available to speak, but he contributed a letter of support for the plan as well. Many of the speakers addressed that upon its opening in 1984, the AT&T Building’s arched public space was dark and underutilized, and that Johnson was a proponent of adaptive reuse.

Architecture critic Paul Goldberger, who had previously testified his support for the 550 Madison team’s changes to the building (and its landmarking), also spoke, but this time disclosed that he had been working as an outside consultant on the project. Goldberger had drawn criticism after an article in The Real Deal revealed his role, and that he subsequently had not revealed his ties to the tower’s management team prior to testifying. Speaking to AN, Goldberger admitted that he had made a mistake in not disclosing his involvement sooner but stood by his criticism of the building’s underutilized public space as having remained consistent throughout his career. His role in the project, he said, is that of a historian and someone who has intimate knowledge of the building.

The praise wasn’t unanimous. Liz Waytkus, executive director of Docomomo’s U.S. chapter, criticized the new windows on Madison Avenue as they would allegedly stray even further from the tower’s original design intent and create a false sense of openness for an enclosed area. Concerns were also raised over the replacement of Johnson’s original articulated paving in favor of a simplified circular plan. Preservationist Theodore Grunewald spoke to the need to preserve 550 Madison’s “forest of columns” design and the relationship of void-to-solid between the cavernous underside and upper mass of the tower.

Ultimately, the commission adjourned without making a decision. They needed time to consider the new scheme and accompanying testimony, and more importantly, lacked the number of commissioners required for a quorum. The LPC will reconvene and discuss the matter again at a future date. The entire presentation shown at the January 15 meeting is available here.