Off I-95 in the northern Bronx, just past the swamps at the mouth of the Hutchinson River and the paved paradise at Bay Plaza mall, arise 35 massive, brick and concrete tower blocks. Most residences nearby are single-family, but Co-op City’s 24-story towers shoot out of the ground like sore, red-brick thumbs. But, as out of place as they seem, there are many similar complexes all around New York City and the rest of the country: Stuyvesant Town by the East Village, Riverton Square in Harlem, and the gone-but-never-forgotten Pruitt-Igoe projects of St. Louis.

According to Adam Tanaka, a New York–based urbanist who studied these Bronx housing blocks for his Harvard graduate dissertation, Co-op City is the country’s largest and most successful cooperative living facility. Many of its 35,000 residents have been living in them since they opened 50 years ago.

In a mini-documentary published with CityLab, entitled “City in a City,” Tanaka interviewed residents, building managers, representatives, and others involved in the conception of the towers to understand what makes these buildings so successful compared to other projects. On top of interviews and historical analysis, documentary footage shows what life at Co-op City is like. During most weekends of fair weather, tenants and local merchants buy and sell art and food, local musicians perform while residents dance, and children play on the swing sets. Wildlife even has a large presence there: residents have reported seeing deer.

What is so special about Co-op City that allows for beautiful scenes like this to be the norm?

Tanaka suggests the towers owe their success not to the City of New York, nor to any federally-funded programs, but to their fellow resident, architects, and the coalition of labor unions responsible for the towers’ development. The documentary highlights several of the complex’s relatively unique features: a ban on market-rate apartment resale, permanent rent control (which was established in the early ’70s after the state tried to increase rents for Co-op City’s tenants), affordable down payments, an elected representative board, self-funded maintenance, and a racially, culturally, and financially diverse group of tenants. But architectural features like larger-than-average apartments with grand windows and ample living and storage space, as well as multiple communal parks and green spaces—all of which was designed by architect Herman J. Jessor, inspired by Le Corbusier’s Villes Radieuse and Contemporain—play major roles, as well.

In the documentary, Alena Powell, a resident of Co-op City since 1973, said a friend from the Upper East Side “was amazed because [Powell’s] living room could hold her [friend’s] living room and kitchen all together.” Powell also “likes the fact that [she’s] not on top of other people as if [she] was living in Manhattan.” Other residents remark about how “spacious” the apartments are, and how they love the consistent natural light.

Pleasing as they may be for many who live there, the Co-op City buildings were (and are) not without criticism. According to an article in Curbed by historian James Nevius, the Co-op City buildings stand as a testament to the ethics of erasing “slums,” and to the power of the infamous Robert Moses, whose “bulldoze it” approach to entire neighborhoods is a highly-debated matter, to say the least. During construction in the early 1970s, many rallied against the design and construction of the towers, citing the cheap and unpleasing exterior. Nevius cites Jane Jacobs, who stated they were “truly marvels of dullness and regimentation, sealed against any buoyancy or vitality of city life.” Nevius also references criticisms by the AIA: “Similarly, the American Institute of Architects complained that ‘the spirits of the tenants’ at Co-op City ‘would be dampened and deadened by the paucity of their environment.'”

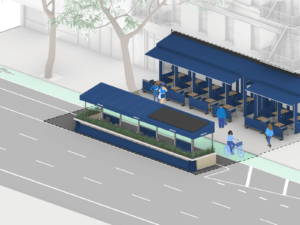

However, many in Tanaka’s documentary do not share those opinions and come to the towers’ defense. Ken Wray, former executive director of the United Housing Federation, says “the aesthetic was ‘Why waste money on the outside of the building?’ You don’t live on the outside of the building…People driving by might think it’s ugly but people who live there know what [the apartments] look like.” Often overlooked, too, is a sprawling meadow laced among the buildings. According to Nevius, over 80 percent of Co-op City’s footprint is dedicated to landscaping: grass and trees with play structures, courts, benches, and market stands on the perimeter. For the people who use these daily, these are helpful amenities that similar developments do not have.

Co-op City raises questions about the emphasis on policy or architecture, about interior design versus exterior, about the house and the outdoors, and about ownership and citizenship. Regardless of where one lands on these issues, there’s something to be learned from these 35 towers in the Bronx.