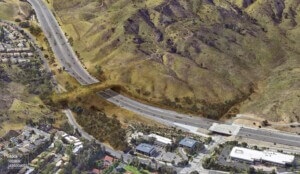

Last week, Texas judge James Shoemake ordered the Fort Bend Independent School District to halt construction after the remains of 95 black prisoners were unearthed on a property it was building on. The site, once known as the “Hellhole on the Brazos,” was the former Imperial State Prison Farm, the infamous home of numerous prison camps and sugar cane plantations where slaves lived and worked in hellish conditions before their subsequent deaths. The property is located in Sugar Land, now one of the wealthiest and fastest-growing cities in Texas just southwest of Houston, but which once served as a graveyard for slaves. It was there, after the district broke ground for a new school, where archaeologists exhumed a massive, 19th-century graveyard of nearly 100 bodies that had been concealed five feet beneath the soil in dilapidated pinewood caskets for decades.

According to NBC affiliate KPRC, Judge Shoemake ordered the school district to halt construction so that the human remains could be examined and investigated at the site.

“This find is very different from any other,” Judge Shoemake said in an interview with KPRC. “We have a history that’s different. I want some more effort. This is important stuff. Families and communities are affected by this. You came here for permission [to build]; I’m not going to give you permission.”

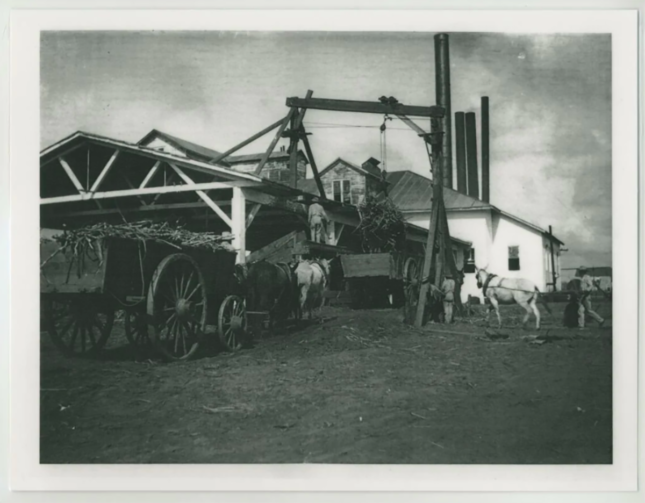

Sugar Land has a unique and shocking history. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the town, located along the Brazos River, served as the epicenter of the country’s sugar industry. The convict-lease system flourished throughout the region, targeting former slaves who were leased by the state to private businesses and forced to work in coal mines, plantations, railroads, and state projects. According to The Washington Post, the black “convicts” were imprisoned into the system for offenses as minor as homelessness, flirting with white women, or petty theft, yet they were made to work from sunrise to sunset in the fields, occasionally until they “dropped dead in their tracks.”

The Fort Bend Independent School District’s construction site encompasses land that was called “Imperial State Farm Prison Camp No. 1.” Conditions were so horrific that prisoners wrote songs about how they would rather die than live another day of beatings, whippings, and slaving under the hot sun.

Private contractors did not care about the health and well-being of their workers. According to W. Caleb McDaniel, a history professor at Rice University in Houston, the convict-leasing system experienced tremendously high levels of disease and mortality. If a prisoner died, a contractor would simply demand a replacement prisoner from the state.

More than 3,500 prisoners of ages ranging from 14 to 70 years old died between 1866 and 1912 when lawmakers finally outlawed convict leasing out of utter shock at the death rates.

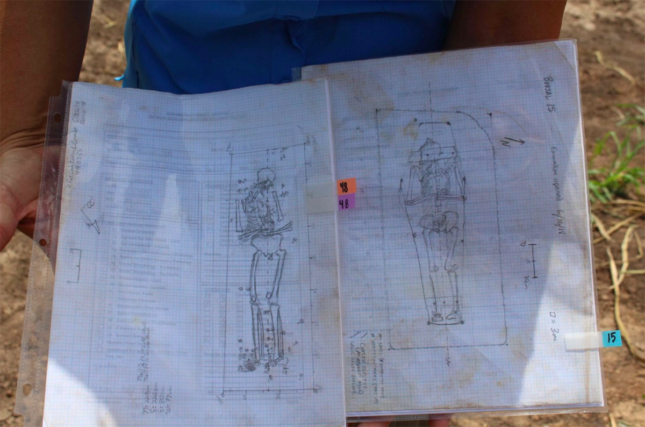

This past summer, a team of archaeologists requested permission from the Texas Historical Commission to conduct a more thorough investigation of the human bones salvaged from the cemetery. Their main goal is to perform DNA testing on the remains in order to identify the prisoners.

The Fort Bend Independent School District shares this ambition, telling KPRC that “our sole mission is to educate students and we only exist to learn. The more knowledge we have the better. We want DNA testing. We want answers, we want to connect the body with the name, and we want to tell the story of an individual.”

As of last week, Judge Shoemake said he hopes to reconsider his decision to halt construction by March 2019.