There’s been something of a renaissance lately in inflatable architecture. In the past few years alone, this ephemeral typology has been at Collective Design Fair, Performa 17, and the Park Avenue Armory. Inflatables emerged in the 1960s as a means of expressing dissatisfaction with established cultural norms about life, work, and society. They were seen as potentially revolutionary structures that allowed for experimentation with space in order to influence social, psychological, and physical cognition through the built environment.

Inflatables were originally invented by the U.S. military with Cornell aeronautical lab engineer Walter Bird to deploy radio antennae in 1948. Bird, often referred to as the father of the field, is credited for taking this military technology and popularizing it in 1959 by collaborating with Paul Weidlinger on an inflatable roof for the Boston Arts Center Theater. In the ’60s and ’70s, when techno-optimism about the future reached its peak, Buckminster Fuller proposed a massive dome over Manhattan, while Frei Otto envisioned one to shelter 40,000 people in the Arctic Circle.

What came next in “inflatotecture” was symptomatic of the counterculture era, which viewed it as a way to construct space for dissent and experimentation while taking advantage of lighter, stronger construction methods and new audiovisual technologies.

Ant Farm, a San Francisco–based architecture studio, designed inexpensive and disposable structures out of vinyl for counterculture “happenings,” and anyone attending them could buy the group’s Inflatocookbook, a comic detailing step-by-step how to make one’s own enclosure (a practice common among collectives to disseminate information and design about inflatables). Other contemporaries included the U.K.’s Archigram, Italy’s Archizoom, and Germany-based Haus-Rucker-Co.—all of whom envisioned inflatable architecture as a way to explore theories about spatial production, social organization, and consumption.

Experimental inflatable architecture continues to be a form that designers use to examine contemporary social problems and to radically play with form and space for its own sake.

The following projects stretch the medium to its limits, showing how the next generation of inflatables can generate new experiences.

Looking to practice new forms of architecture outside of the traditionally accepted profession, New York-based designer Jesse Seegers employs the term “spatial practice,” a framework to create structures that draw from architectural knowledge but are equally related to other disciplines.

For example, the Potlatch Pavilion was an ethereal inflatable for a gift exchange party, referencing the Pacific Northwest indigenous American tradition where one’s status is derived from how much you can give away, rather than how much wealth you possess. Here, the inflatable was deployed to “construct alternative systems of political economy.”

Seegers’s recent projects include a temporary yoga space called Yoga Dome, which premiered at the opening of Sky Ting Yoga; an installation at a Pioneer Works exhibition on Ant Farm; a concert backdrop for musician SOPHIE’s live tour; and an inflatable landscape for musician Oneohtrix Point Never’s M.Y.R.I.A.D. concert at New York’s Park Avenue Armory.

In 2017, Seegers helped French, Los Angeles–based architect François Perrin bring Reyner Banham and François Dallegret’s 1965 conceptual drawing The Environment Bubble to life as a site-specific installation for dance workshops in Brooklyn Bridge Park and Central Park as part of Performa 17.

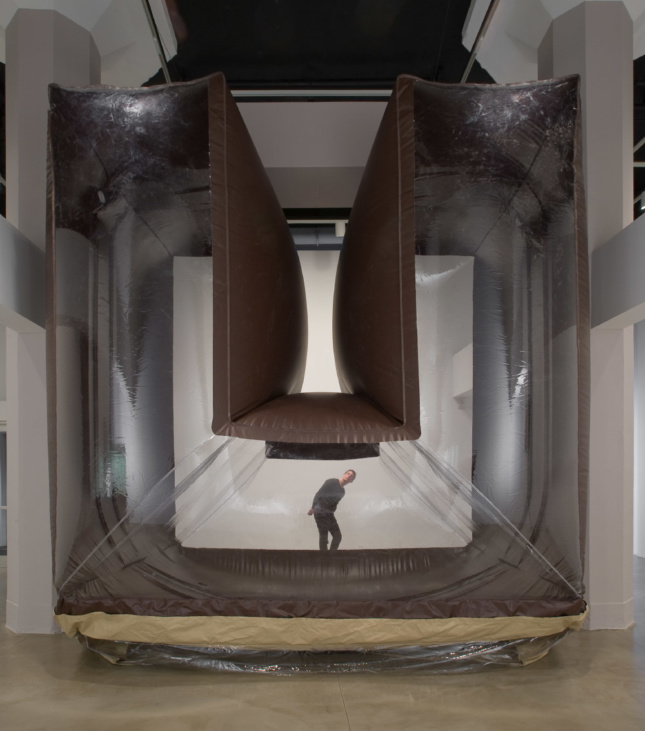

“An inflatable space in process speaks to the bodies we have. It’s a fleshier, time-based architecture,” said Alex Schweder. The self-proclaimed performance architect began working with inflatables in 2005 at the American Academy in Rome, where his first blow-up installation, Sick Building Sequence, encapsulated feathers floating inside of a translucent plastic “room.”

Since then, his inflatables have traversed Collective Design Fair, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the Venice Architecture Biennale, Tate Britain, and Performa 17. These include a “room” with photosensitive fur, an inflatable hotel inside of a cherry picker, a floor-to-ceiling mass that collapses and expands into and away from itself, and a spiderlike robot that inflates and deflates to reconfigure space on a dance floor.

What’s next? Schweder is working with a team of international artists on a traveling show that responds to László Moholy-Nagy’s Mechanized Eccentric, which will debut at the Bauhaus 100th anniversary next year.

Formed in 2014 as a volunteer nonprofit organization dedicated to designing for the public realm, the group is officially the Seattle-based chapter of the international Design Nerds Society. Known for their inflatables, Seattle Design Nerds is a multidisciplinary collab started by Jeremy Reeding and Trevor Dykstra. The pair works with other local architects, designers, and artists on public interest projects to “make Seattle a little more awesome.”

True to their mission, Reeding and Dykstra’s first inflatable was a large-scale installation for the 2014 Seattle Design Festival Block Party, a pop-up space shaped like a giant monster and filled with random objects for play. The team veered into the conceptual realm with The Gas Trap, a performance work where a car’s tailpipe seemingly fills the inflatable to illustrate our dependence on gasoline.

Last year they dreamed up an installation at the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park composed of eight cuddly, inflatable orbs that change color when bopped. For the 2017 Seattle Design Festival Block Party, the group envisioned an illuminated inflatable mural crafted by visitors at the event with Velcro pixels. Their latest work for Cooper Hewitt’s Design with the Other 90% features a giant egg-shaped inflatable that will debut at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center in Seattle in mid-September.

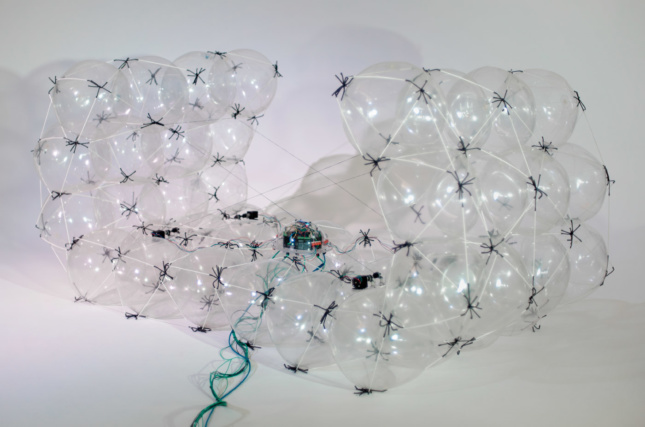

A young Nicolas KK grew up in Brazil in a family of hot air ballooners. From these beginnings, he developed an innate understanding and appreciation of the form. Putting his “family stuff” to good use, he started making his own blow-ups while studying industrial design at the Maryland Institute College of Art. That trajectory has continued through collaboration with digital, audio, and light artists in a shared studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn, called Future Space.

Inspired by the inflatables of the 1960s and ’70s, Nicolas KK produces experimental structures by applying his expertise in computational design. His digitally driven experimental performance pieces create “dynamic” qualities and always include a programmable element that directly responds to existing digital infrastructures or naturally occurring biomimetic systems.

Nicolas KK plans to study Integrative technologies and architectural design research at the University of Stuttgart in Germany, where he will continue to work with inflatables and collaborate with other artists on projects that respond to the emerging computational environment. In December, New York’s New Museum will debut his work in an online exhibition described as “the original live desktop theater internet television show.”

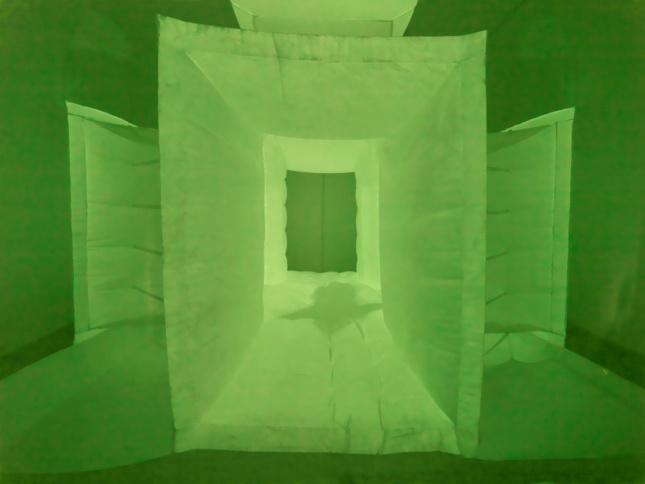

Matt Muller, Augie Lehrecke, and Levi Bedall spearhead the Rhode Island-based design collective Pneuhaus dedicated to the mastery of all things inflatable, specifically spatial designs, temporary structures, contemporary art, and large-scale installations.

It all started at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 2014 when Muller and Lehrecke designed a handful of different inflatables inspired by Art Farm’s Inflatocookbook. The university hired them to continue to explore those ideas and design a space for the school’s annual design conference. Soon after, Beddall joined Muller and Lehrecke when they got their first professional commission to design-build and perform a circus for the RISD Museum.

Since then, the trio has imagined transient spaces for Spotify, Burning Man, and Brown University. Ranging from inflatable fabric prisms built around the fundamental properties of light to inflatables outfitted with pinhole cameras, their growing list of projects develop as iterations of previous works. Their most recent project, Compound Camera no. 2, is a new iteration of the pinhole camera inflatable dome as a giant tunnel at the LUMA Projection Arts Festival in Binghamton, New York.