During my four decades as an architecture critic, I developed close personal relationships with several of my subjects, including Charles Moore and Frank Gehry, although, unsurprisingly, our dealings became far less amicable when my enthusiasm for their work waned. My longest direct connection to those I’ve written about has been with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. But that intimate bond had both its rewards and perils, as I recalled after his death on September 18 at the age of ninety-three.

Criticism of architecture is complicated in ways that differ significantly from other mediums. Authoritative evaluations require that you get inside the works in question to make a responsible judgment, especially in the case of private houses or other properties not open to the public. One must also have technical information in order to provide an accurate account of a building’s physical characteristics.

An art critic may easily determine the dimensions and components of a painting by seeing it on a gallery wall, a theater or music critic by purchasing a ticket for a performance, or a book reviewer by obtaining a copy of the publication. But an architecture journalist had best be on speaking terms with his subjects, a lesson I repeatedly learned the hard way with Venturi and Scott Brown.

Early in my career I wrote a puerile review of their Penn State Faculty Club (1974-1977) in State College, Pennsylvania. Today that article makes me cringe. In an attempt to shock, I called their charming homage to Shingle Style domesticity “a whorehouse without a second floor” because its upper-story fenestration was purely ornamental. Their jest was no crime, but I was trying to establish street cred as a tough critic. My crude epithet outraged the architects, of course, and I was in the doghouse for years afterward.

Fortunately, Bob and Denise, as I came to know them, were very fond of Rosemarie Haag Bletter, the architectural historian who had been among the first academicians to include their work in college-level modern architecture courses in the 1960s. She would also become my future wife. After we married, I tried to make amends with the two architects, whose susceptibility to feeling wounded was exacerbated by their having lost numerous architectural competitions they deserved to win.

To my relief, I eventually received a handwritten letter from Venturi in which he announced, with courtly formality, that because Rosemarie had accepted me in matrimony, they forgave my youthful indiscretion. However, the dangerous flip-side of being shunned by one’s critical subjects is becoming too close to them, and I admit that I gradually did cross the line into friendship with Bob and Denise. They were prominently featured in Michael Blackwood’s 1983 documentary film Beyond Utopia: Changing Attitudes in American Architecture, which Rosemarie and I wrote and for which we conducted the interviews.

When we were guest curators for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1985 exhibition High Styles: Twentieth Century American Design, we recommended that they be hired to create the show’s installation; they were, and their work—a witty Pop mounting that reflected their love of the decorative arts—was widely admired. It was no surprise that around that time they were also designing equally delightful furniture for Knoll, china for Swid Powell, flatware for Reed and Barton, rugs for V’Soske, and even a cuckoo clock for Alessi.

Still, there were risks. In 1991, having heard from the National Gallery’s board chairman, Jacob Rothschild, that Venturi and Scott Brown’s problem-plagued Sainsbury Wing was nearing completion, I gained access to the closed construction site on Trafalgar Square by posing as a member of the architects’ firm—hardhat, clipboard, and all. Exhilarated by the nearly finished project, I urged the magazine I worked for to run pre-completion photos of the new building in order to land a scoop. Breaking the press embargo caused an initial Venturi eruption—he concealed a volatile Italian temper beneath his buttoned-down Philadelphia preppiness. But after an interval I was absolved once more and the Sainsbury Wing is now justly considered their masterpiece.

Thereafter, considering their advanced age and towering historical stature, I decided to write about them only when I had something positive to say. And I was delighted when I could praise without reservation a late-career gem, their Dumbarton Oaks Library of 2001-2005 in Washington, D.C., a veritable concerto in patterned brick, alive with architectural syncopation and functional logic. It would be my last review of their work to appear during his lifetime. He retired from practice in 2012, as Alzheimer’s disease sapped his formidable creative and intellectual powers, a loss all the more poignant because he was the most learned architect I’ve ever known.

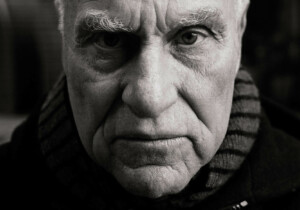

Bob’s funeral was held six days after his death, on a cool, overcast afternoon when some seventy family members, colleagues, friends, and caregivers gathered in Newtown Square, on the outskirts of Philadelphia, at the Willistown Friends Meeting, an eighteenth-century Quaker meetinghouse of exquisite rigor and simplicity. The tranquil, timeless setting—a rural scene of rolling hills and low fieldstone walls—seemed like an Andrew Wyeth painting come to life (the artist lived at Chadds Ford, fifteen miles to the southwest). It was hard to believe that one was still in the violent and hate-saturated America of 2018.

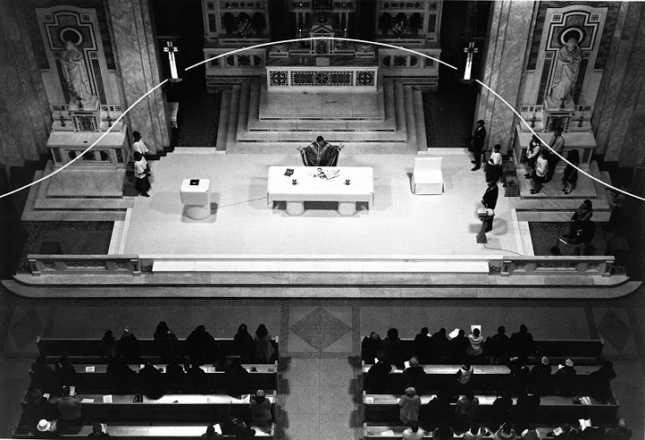

Venturi’s parents, both from Italian Catholic families, converted first to Unitarian Universalism and then to Quakerism. Their only child took their faith’s precepts of nonviolence and pacifism seriously enough to become a conscientious objector during World War II and defined himself as “a proper Quaker” until the end of his life. The officiant at his ecumenical funeral was not, however, a Quaker elder, but rather Father John McNamee, a retired Roman Catholic priest with early ties to the Catholic Worker Movement and who was honored for his social activism in inner-city Philadelphia. He had also been responsible for overseeing the Venturi firm’s 1968 reconfiguration of St. Francis de Sales Church in Philadelphia, which was spurred by new liturgical practices advanced through the Second Vatican Council.

As Father McNamee pointed out during the funeral service, Venturi’s respect for ordinary Americans’ values and aspirations remained paramount. The priest began by reading the Beatitudes, the very kernel of the Christian message, albeit one ignored by many present-day American Evangelicals, and then quoted Father Daniel Berrigan, the 1960’s Jesuit antiwar crusader.

The ceremony featured two of Quakerism’s hallmarks: ten minutes of silence, followed by spontaneous contributions from congregants who spoke as the spirit moved them. The emotional highlight of the gathering came in a sequence of personal reminiscences by four home health-care aides who cared for Venturi during his final years.

The crucial role that such unheralded heroes of everyday life play in our society has never been more immediately expressed nor as touchingly clear to me. And although each spoke separately, their shared sentiments resounded as if they were harmonizing soloists in a gospel choir. One of them, Pat Thompson, was too overcome to speak directly, so her heartfelt tribute was read by a colleague, Wanda Whittington.

In their moving and funny anecdotes, Verna Wood and Carolyn Heller likewise told of growing to love their sometimes difficult but inevitably appreciative client. Several of them said that they had no idea at the outset of their service that Venturi was a world-renowned architect, and that although they came to appreciate his exceptional stature, it was the man, not the artist, they would miss most. This was the all-pervasive feeling in the room.

After the eulogies, the mourners filed out to the cemetery, shaded by mature trees and dotted with low headstones of nearly identical design. After the squared-off, unfinished wood coffin was lowered into the grave, Venturi and Scott Brown’s only child, the urban planner and documentary filmmaker James Venturi, laid a homemade wreath of laurel leaves next to the grave; the victor’s laurels with a down-to-earth ethos.