A fascinating and thoroughly researched book, Space Packed: The Architecture of Alfred Neumann, by Rafi Segal (2018, Park Books) investigates the rise and fall of Alfred Neumann, Israel’s perhaps most major, and yet still unknown, architect. In addition to providing a compelling biography, Segal makes the claim for Neumann’s unique significance and demonstrates how his work captured important conversations and conflicts in Israeli architecture of the 1950s and ’60s; Neumann’s work was a cipher for debates about the future of architecture in the new state. Lavishly illustrated with drawings and photographs and concluded by an appendix that contains Neumann’s own writings, Space Packed convincingly asserts that this man at the margins was ahead of the times.

Alfred Neumann was born in 1900, trained with Peter Behrens and Auguste Perret, survived World War II as an inmate at the Theresienstadt concentration camp, and then emigrated to Israel in 1949, a year after the state was founded. He became dean of Haifa’s prestigious Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and, in 1956, published the first part of a theory that would inform his work for decades: a pamphlet that called for architecture’s reform through a new, humanizing system of proportion to determine a better measurement unit. Buildings were to be seen not as singular large forms, but as an aggregate assembly of smaller, repeated, and interconnected units that could render them more humane.

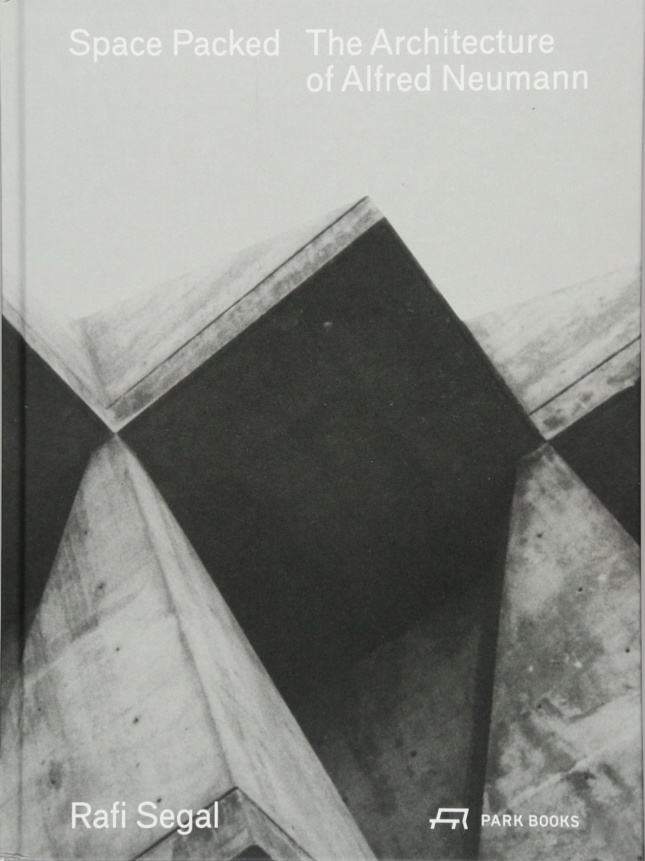

Beginning with his astonishing Bat Yam City Hall, and through the fabulous seaside holiday villages for Club Méditerranée and Kiryat Yam, Neumann became known for buildings with complex interfaces between interior and exterior. Space packing came to be understood as a mode of making architecture—in her obituary, Ada Louise Huxtable called him the father of the movement—structured on polyhedral forms that could be “packed” for maximum spatial efficiency. The polyhedral and non-orthogonal geometries these ideas produced were impressive in their capacity to relate to local conditions of climate, light, and topography. Bold colors were an important element of Neumann’s work and were used as a way to interpret programmatic space. Pattern and repetition were paramount in space packing.

Neumann’s architecture had a major impact in its time and is still alluring today. Zvi Hecker joined Neumann’s studio in 1952 and became a close collaborator for life. Moshe Safdie spoke of the affinity he felt with Neumann’s work, and, for Neumann’s obituary in 1968, Architecture d’Aujourd’hui gave him an entire page alongside Walter Gropius’s full-page announcement. During their lifetimes, Gropius said of Neumann that he had developed the only meaningful system of human proportion except for Le Corbusier.

The history of Israeli architecture writ large is a history of dynasties—the Rechters and Sharons among them—to which Neumann, a minor architect, did not belong. For the last two years of his life, Neumann lived in something of an exile in Canada, where he founded the architecture department at the University of Laval in Quebec City. Caught in controversy around his Danciger Building (1963–66), as well as Israeli architecture’s tilt toward historicist postmodernism after the Six-Day War, Neumann no longer had his finger on the pulse of the country’s architecture scene. He was buried in 1968—as a Christian in a Catholic cemetery in Quebec City—per his request.