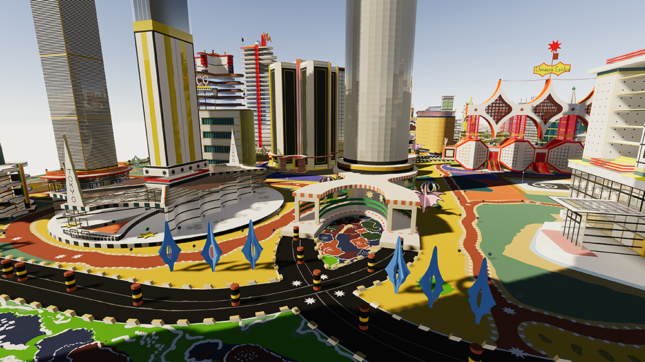

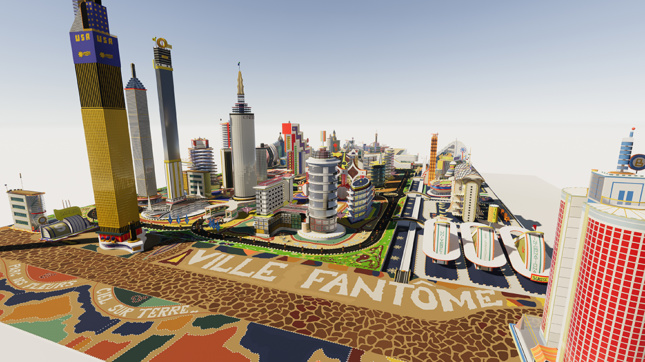

Upon arriving at the Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez’s City Dreams retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)—the first full retrospective for him or any other African artist at the museum—there is a feeling of ascension. Having climbed many floors to get here, one reaches a room where humans hover over the cities and look down, not up, into the buildings, windows and boulevards. The viewers look like gods around a creation, but Kingelez’s work decidedly belongs in the kingdom of this earth.

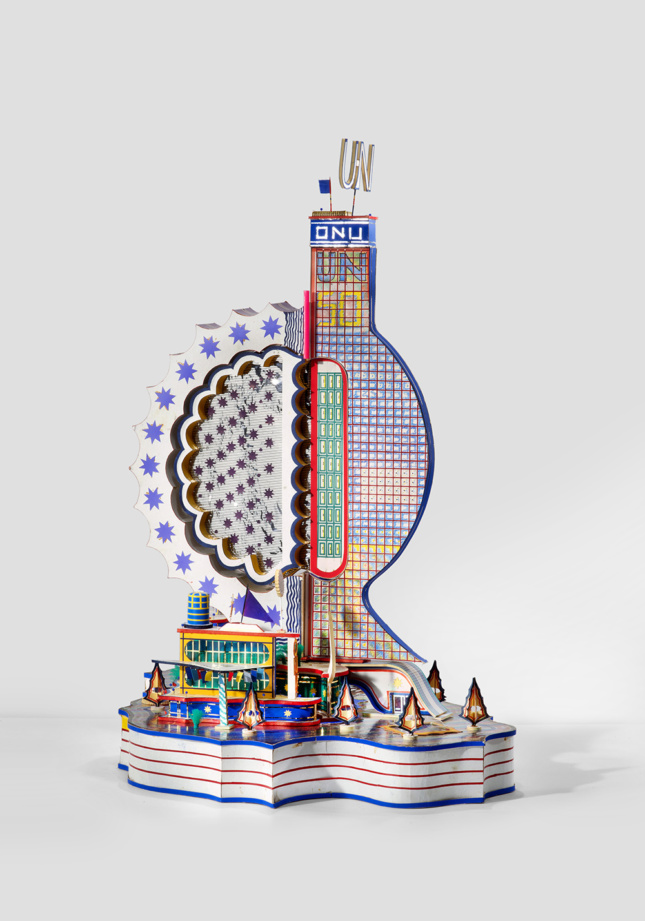

His “extreme maquettes,” as he referred to the ornate buildings and cities he constructed, are all units of a larger project that demonstrates the desire for a harmonious future among all peoples; beauty and grace as a reflection of this harmony; and a rejection of the violence commonplace in the immediate post-colonial era, a legacy of the country’s rule under the brutal Kingdom of Belgium. “I’m dreaming cities of peace,” he explained. “I’d like to help the earth above all.” In his Project Pour le Kinshasa du Troisième Millénaire, a re-envisioning of Kinshasa, “police and prisons do not exist.” It was, in essence, the cosmopolitan post-independence vision of the era. Kingelez’s, however, extended beyond dreams of self-rule, asserting a seat at the table for the African imagination of what was possible in the new, truly free world.

Bodys Isek Kingelez was born Jean Baptiste on August 27, 1948 in the town of Kimbembele Ihunga in what was then the Belgian Congo. At the age of 22, after receiving his high school diploma, he left for Kinshasa, the capital city. There, he studied economics and an assortment of other subjects like industrial design at the University of Lovanium (now Kinshasa).

“I came from a traditional village where everyday I used to watch the men making masks or working at the forge,” Kingelez explained of the mysterious origins of his craftsmanship. “There was no need to learn, then, what I used to see all the time.” Remarkably, he didn’t travel outside Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) until 1989, and so had never interacted up close with architectural design in other countries. Undoubtedly, however, the colonial Belgian Art Deco buildings that lined the streets of Kinshasa and the eccentric palaces (including a pagoda) constructed around the country by ruler Mobutu Sese Seko indubitably seeped into his sense of aesthetics.

His first maquette, he recalls, came to him in a dream one night. Feeling “compelled” by the revelation, he made the work under its direction. Throughout his life, his process was similar. First the title came to him. Then the vision to make it, which “gives me all I need, even the shape and colors.”

On one such instance, in 1978, he showed the result of his work, Musee National, made from simple tools like paper, glue, scissors, and razors, to the Institut des Musées Nationaux du Zaire. The museum staffers doubted Kingelez could build a work of such sophistication and challenged him to make another work on site, leading to his Commissariat Atomique. The impressed museum hired him to become a “technicien restaurateur” of historical artifacts. The experience of working with invaluable abstract art traditional sculptures left a mark on Kingelez, who confessed “the ruined statues led me to the pinnacle of my skills”

Like these African masks of old, the maquettes aim not to depict reality but act as a record of a time and the ideas and the imagination that marked that time. In Kinshasa, Kingelez absorbed elements of the national movement for African authenticity. It is under the aegis of this movement that we see Leopoldville become Kinshasa, the Congo river and the nation, Zaire. As a former Commissioner of National Orientation put it, it was a movement based on reaching into the past to find traditional elements “which adapt themselves well to modern life, those which encourage progress, and those which create a way of life and thought which are essentially ours.” A self-described “favored poet of his traditional sources,” one can imagine very clearly the figure of Kingelez hidden away in his studio in Kinshasa, hovering over a project with tweezers in hand, moving the hitherto possible around and making way for the impossible.

But, like his previous work in the museums on African masks of old, Kingelez’s project was a restorative one. Having himself traveled from the village to the city and later the metropole, his work rejected hierarchies and the geographic isolation of the human experience. Instead, it collapsed the time between an African past and a future where no societies were more advanced than others.

His 1994 work Kimbembele Ihunga, a reimagining of his home village, represented a “concrete imaginative leap” and “a real bridge between world civilizations of the past, present and future.” Filled with skyscrapers and tree-lined streets, the boulevards provide “pleasant, easy access to all parts of the town.” A stadium named after himself, “Stade Kingelez,” sits in one corner of the town, and in front of the town center stands a monument of a man holding a book who “simply represents the intellectual heritage of common sense and good manners which belongs to multicultural people.” “People flock here,” he said, “because the wind blows in off the sea and the mountains, refreshing its complex beauty in which all the heightened colors join forces consistently to create an environment where everyone can feel at home.” The town and dream of it was not one he would ever live in, but one which lived in him.

Multiculturalism is paramount in Kingelez’s work, and we see it not only in the foreign design present in some of his Congolese maquettes, but also in the maquettes dedicated to places, like the outstanding purple and yellow Mongolique Sovietique (1989), in Palais d’Hirochima (1991) whose tiered, raised buildings are inspired by a real imperial palace with paper lanterns suspended between buildings, and Céntrale Palestinienne (1993). His New Manhattan, built a year after the attack on the World Trade Center, is a take on the Manhattan skyline with a third tower filled with water whose “cooling effect will prevent any bombs from exploding.”

In insisting on a world crafted for peace, Kingelez, who died three years ago, challenged our imagination to consider what this would require. His work, he insisted, was as much a “gauntlet thrown down to professional artists” as a prodding of our “ability to create a new world.” With salvaged materials like colored paper, scissors, and glue, the self-anointed “prophet of African art” constructed dream cities and a universe of peace, equality, and equity for all. Surely today, with better instruments, we can reflect on his vision and fulfill it down here on earth.

Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

On view through January 1, 2019