The exhibition Zevi’s Architects: History and Counter-History of Italian Architecture, 1944-2000, curated by Pippo Ciorra and Jean-Louis Cohen at MAXXI in Rome, interweaves three strands of research and documentation based on the life and work of Bruno Zevi: his biography; an architectural history that brings together a selection of projects culled from Zevi’s writings; and finally Zevi’s media, which extend from books to TV broadcasting and exhibitions. It presents, on one hand, Zevi’s voice (which one can literally hear broadcast on TV) and the scope of his work as an architectural critic, theorist and public intellectual. Encountering Zevi’s voice and work is important, especially for generations of architects and historians who know Zevi as an “operative critic,” the title given to him by Manfredo Tafuri in Theories and History of Architecture, and the title that Zevi himself embraced when he founded the Institute of Operative Criticism. On the other hand, the exhibition presents a history of Italian architecture after World War II that brings together well-known projects along with lesser-known ones to narrate an understanding of architecture—one that is not only deeply rooted in society and social transformation, but also diverse.

It is this history that makes a difference and gives the exhibition its taste: a fresh view of Italian architecture after WWII that begins with usual suspects, but expands to include more unfamiliar projects, singular attempts, and different trajectories. The selected projects are presented with quotes from Zevi’s writings about them. The selection starts with projects that are common to the architectural discourse in the fifties and sixties and then expands to include projects that are more idiosyncratic. It is through this selection that Zevi’s voice forms as well—initially part of common discourse and then becoming more individualized. The result is an exhibition where Zevi becomes a posthumous curator of Italian architecture in the second half of the 20th century. And by suggestion, one can conclude that today’s operative critic is a curator.

Zevi’s voice carries controversies within itself. We learn, for instance, that Zevi, an Italian Jew, emigrated to England and the United States, and became a member of USIS (United States Information Service). USIS was a U.S. government agency devoted to explaining American policies and views to foreign publics during the Cold War. Broadcasting was an important activity of USIS. Zevi’s fascination with Frank Lloyd Wright and American architecture may have something to do with this, and his entire emphasis on organic architecture as the architecture of democracy may have to do with this as well. Even his emphasis on broadcasting his views on TV may have been influenced by this. There is perhaps no surprise in this congruity between thoughts and actions. Yet considering Italy had one of the strongest communist parties and traditions in Europe, this information places Zevi’s work in in a more controversial light within its context and helps to distinguish him as a distinct voice.

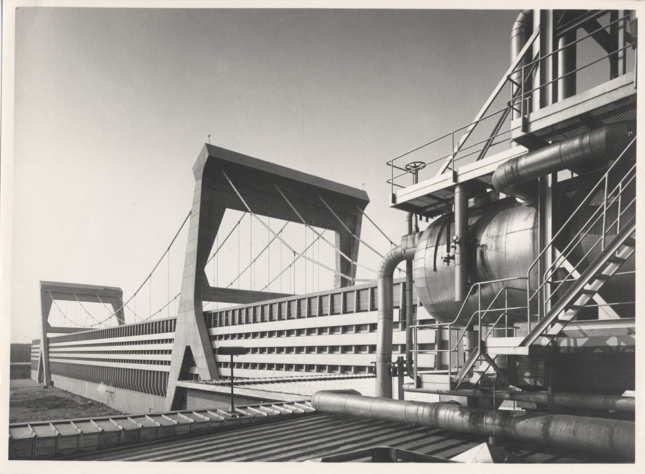

What does one find in this voice and through the exhibition? One finds an openness to accept every example of architecture with its politics as part of a diverse cultural and social landscape. One finds determination to discuss architecture first as the work of an architect and with terms and constraints set by design, and then consider the roles design decisions play in social and cultural realms. For instance, Sergio Musmeci’s Ponte sul Basento in Potenza is an engineering feat of elegant form but also a “pedestrian walkway filled with surprises” leading toward the city from the industrial zone. In Zevi’s words, there is joy of architecture.

One way to think about Zevi after the exhibition Zevi’s Architects is as the critic of difference. This is not a difference that is articulated or generated through the analysis of historical conditions. This is difference in the sense that everybody has a slightly different view of a given situation. Such a difference of views may be constructed by means of history but it is also a matter of hic et nunc. It is difference that occurs because everyone occupies a slightly different place and hence may have a different view. It is the kind of difference that constitutes a public realm according to Hannah Arendt: “Only where things can be seen by many in a variety of aspects without changing their identity, so that those who are gathered around them know they see sameness in utter diversity, can worldly reality truly and reliably appear.” Ultimately, this is also the kind of difference that makes democracy possible.

Going through Zevi’s Architects feels like reading a perfect film script. As the story of architecture in Italy after WWII unfolds, the protagonist, the architectural critic develops, takes charge and begins impacting the story. Eventually, the story and the protagonist are intrinsically linked. The exhibition, in presenting a diversified history of Italian architecture, makes visible the work of the critic. Through Zevi’s biography and the selected projects, it allows for a reflection on democracy today and how different it is than today’s populisms due to the difference that constitutes it.