Last night the two agencies in charge of transit in New York kicked off an open house series for the public to learn more about plans to move commuters between Brooklyn and Manhattan during the 15-month L train shutdown. The events are being held over four weeks in neighborhoods that will be most impacted by the closure.

About 70 people filled the cafeteria of Williamsburg’s Progress High School for the first open house, which was jointly hosted by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and the New York City Department of Transportation (NYC DOT). Employees of both agencies stood by boards outlining transit options, science fair–style, as members of the public approached to ask questions about the bus, train, ferry, and bike routes that will carry them to Manhattan and back.

The shutdown begins April 2019. During that time, the Canarsie Tunnel under the East River will close so workers can replace infrastructure that was damaged by flooding from 2012’s Hurricane Sandy. Each weekday, 225,000 riders move through the tunnel, and 50,000 rides take the L just in Manhattan. The agencies are in the process of soliciting community feedback on the transit options; no plan has been determined yet.

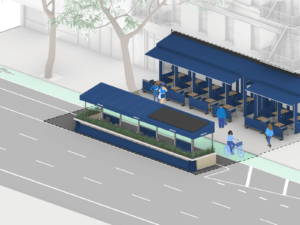

In Brooklyn, proposed changes include three-person HOV restrictions on the Williamsburg Bridge during peak hours, as well as new protected bike and bus lanes to ferry riders between the J/Z/M and G trains, L-adjacent lines the city expects 70 to 80 percent of affected riders will utilize to get across the river. Work is being done to ensure these lines can handle additional capacity, and the bus routes could be upgraded to give buses priority over private vehicles.

The city estimates an additional 5 to 15 percent will use buses only, with new Williamsburg Bridge–bound buses, dubbed L1, L2, and L3, slated to carry approximately 30,000 riders, or 13 percent of the weekday total.

After that, the agencies say five percent of straphangers will switch to the ferry, two percent will cycle to work, and between three and ten percent of riders may use taxis or ride-sharing services for their commute.

In Manhattan, 14th Street (the crosstown thoroughfare under which the L train runs) would be converted into a busway, with only local private car access allowed. A block south, protected two-way bike lanes would be added to 13th Street to accomodate cyclists headed to and from the Williamsburg Bridge, which touches down on the Lower East Side.

The next public meeting is scheduled for Wednesday, January 31, from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. at the 14th Street Y in Manhattan.

Residents had many questions—and more than a few concerns—about the proposed routes.

“The main impetus of the plan is to keep people out of North Brooklyn,” said Felice Kirby, a longtime Williamsburg resident and board member of the North Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. “There are a couple of thousand small businesses and manufacturers who, along with residents, made this area famous. We’re in a lot of trouble if people can’t get into our area to eat, shop, and work.”

She grilled an MTA official on why ferry service wasn’t being expanded to increase the percentage of L-train riders who might use the boats to get to work.

“It’s a timid and meek approach,” she added.

Lifelong Williamsburg resident Vikki Cambos has already started thinking about alternative travel plans. Though she lives off the Grand St L and works off Hewes Street J/M, she is weighing the shutdown as she job-searches. “I don’t want something directly off the L, because that will be a headache,” Cambos said. As another option, she’s considering jobs in lower and upper Manhattan that are easily accessible by trains other than the L.

She’s worried too that the proposed shuttle will add crowds in a neighborhood that’s already undergone extensive gentrification.

“I’m excited to see people move out,” she said.

Jeff Csicsek, a software engineer who volunteers with the North Brooklyn arm of transit advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, wants Grand Street in Brooklyn to be for bikes, buses, and pedestrians only—no private cars allowed. He cited Downtown Brooklyn’s no-car Fulton Street, one of the city’s most profitable retail corridors, as an example of how the streetscape could be retooled to favor pedestrians and mass transit on Grand.

“I don’t think it’s physical changes [that are needed] so much as policy,” he said. “A do-not-enter sign for private cars would make this actually work.”

Even Andy Byford, the newly-appointed president of MTA New York City Transit, showed up to hear the public’s questions. DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg was also in attendance.

“We simply have to get this right,” he told a small crowd of reporters. The MTA, he added, is soliciting community feedback to decide on final transit options.

“The plan is not set in stone,” he said.

This post has been updated with the MTA’s map of possible transit alternatives during the shutdown.