In the unfolding of any design movement, there are outliers who are seen as too far from the mainstream, too quirky to be celebrated by peers and historians. Over many decades of abundant architectural accomplishment, Albert C. Ledner was one of those. But he recently had the good fortune of winning widespread admiration in the months before his death on November 13 at the age of 93.

Born in the Bronx in 1924, Ledner arrived in New Orleans at the age of nine months and left it only for short periods thereafter. His studies at Tulane were interrupted by his World War II service as a lieutenant in the Army Air Corps. While stationed in Arizona he made a visit to Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter work place, Taliesin West, an event that, in his words, “had such a great bearing on my life.” After the war, he finished his degree program at Tulane and spent some time with Wright at his base at Taliesin East in Wisconsin.

By 1951, Ledner had started his own practice back in New Orleans, dedicated not to the Bauhaus-based Modernism largely dominating U.S. architecture of the time, but to the more adventurous variety associated with Wright. And unlike many Wright disciples, Ledner was able to escape the intimidating shadow of the master’s creations to explore his own related design inspirations.

Over a career that extended throughout his final years, Ledner created some 40 houses in the New Orleans area, not only designing them but directing their construction. He was thus a pioneer in the “design-build” process, led by the architect, not the builder, that has only recently been applauded in the architectural community. By proceeding this way, he was able to seize opportunities for unusual structural systems, distinctive uses of materials, and refinement of details without the tedious negotiations and cost premiums for innovation imposed by the traditional design-bid-build sequence.

Ledner’s relatively unfettered design approach led him to construct spaces of unconventional configuration and detail. In one house, he affixed some 1,200 amber glass ashtrays to the exterior, in part because the owners were heavy smokers (considered okay in the 1960s), but mainly because he admired the ashtrays’ circle-in-a-square configuration. In another of his houses, he based his design on the owner’s collection of traditional windows salvaged from the convents for which they were designed—assembling their curved-top shapes both right side–up and upside-down to striking effect.

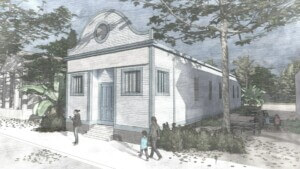

Ledner’s youthful leap into structures of larger scale grew out of his first commission for the National Maritime Union for its meeting hall in New Orleans, a circular volume topped by a roof of radial, pleat-like forms. Pleased with this functional and visually iconic 1955 structure, the union commissioned him to design its buildings in the port cities of Mobile, Alabama; Baltimore, Houston, and Galveston, Texas.

The most ambitious of these Maritime Union projects were the three structures he designed in Manhattan: the Joseph Curran Building in the West Village area, completed in 1964, containing its hiring hall, offices, and training facilities. Two residence halls for union members were completed later in the mid-1960s on two adjoining sites in Chelsea. All three eye-catching buildings have now been successfully and sensitively adapted for new uses. The sculptural six-story hiring hall and training structure, now under city landmark protection, is now the O’Toole Building, an emergency room and medical center. The residential structures, widely recognized for the circular windows that dot their tall facades, gracefully house the Maritime and Dream hotels.

In recent years, Ledner’s daughter Catherine produced a documentary on his life and work that featured a number of key buildings and much of his own charming commentary. She found an able and dedicated collaborator in Roy Beeson, her cousin on her mother’s side. The film was shown in New Orleans last summer and at a September gathering co-hosted by the Modern architecture advocacy group DOCOMOMO New York/Tri-State and AIA New York. For its showing at New York’s Architecture and Design Film Festival in early November, Ledner himself attended and spoke, less than a week before his death. It is good to know that he was at last able to enjoy these heart-warming celebrations of his achievements.

John Morris Dixon is a board member of DOCOMOMO New York/Tri-State.