“Our project is at the end of a seventy-year project,” said Gullivar Shepard, principal at Brooklyn-based Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), of his firm’s St. Louis CityArchRiver design. Back in 2010, MVVA’s team won a competition to rework the landscape around the St. Louis Gateway Arch—technically the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial—to make it more universally accessible, easier to maintain, and more integrated into its urban context. Expanding and popularizing the site’s little-known museum was also a key goal. While the client was technically a foundation, the firm would have to work closely with the site’s owner and preservation-minded steward, the National Park Service (NPS). The challenge was complex: The landscape was hardly a clear-cut expression of Eero Saarinen and Dan Kiley’s designs.

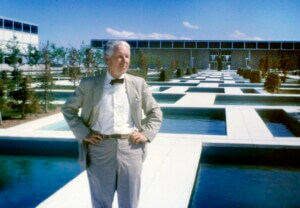

Kiley was on Saarinen’s original design team, whose 1947 proposal won the memorial competition. But the project languished until 1957, when funding became available. Saarinen and Kiley were internationally renowned by then, “so they went back to the drawing board, literally, and came up with a new design for the memorial,” said NPS Historian Robert Moore. “Basically, it evolved from a rectilinear-looking plan to a very curvilinear plan that echoed the curves of the arch itself.” Moore described how the curving paths and ponds were Saarinen’s ideas, while the allées and cypress circles came from Kiley.

The NPS subsequently stepped in and became involved in the design, thinning out Kiley’s dense vegetation. After the completion of a 1964 “final landscape plan” with Kiley (Saarinen had passed away in 1961), the NPS continued without him. Money to build the landscape only became available in earnest in the early 1970s, with much of the landscape elements in place by 1974, though final plantings were made in 1983. During this time, the NPS made small changes to Kiley’s ponds and the special stairs Saarinen had designed. “Again, [there were] many hands in the design,” said Moore.

The resulting shortcomings are numerous. Eighty percent of visitors, said Shepard, don’t even know there’s a museum underneath the arch. Many drive in from the highway, park on the on-site parking lot, take the tram to the top, and leave. The park is also cut-off from the city by highways, which didn’t exist in 1947.

In addition, the decision-making process was complicated by the fact that “this is not an actual historic landscape or actual historic building or fabric,” said Shepard. “It’s a monument to a historic concept, a moment of time.”

MVVA broke down the proposed interventions into 14 key decision points, each a constituent part of a larger landscape resuscitation.

Ultimately, key interventions included building new, fully accessible paths—embedded in the landscape—that snake down from the arch plateau to the river, replacing the allées’ infestation-prone ash trees with London plane trees, and bulldozing the parking lot to create a new seven-acre park that connects to Washington Avenue, a major urban corridor of St. Louis. The biggest (and perhaps most controversial) intervention was a new circular museum entrance embedded in a berm that leads up to the arch plateau. A new vegetated bridge, which leads directly to the new museum entrance, will replace caged highway overpasses.

While the stakes are high for the memorial, this project could have broader implications for other NPS sites. “This was the project that everyone in the Park Service has been very carefully watching,” stated Shepard. If the NPS, an organization “not built for change,” can successfully update a complex site like this, then perhaps similar projects could be possible in other cities.