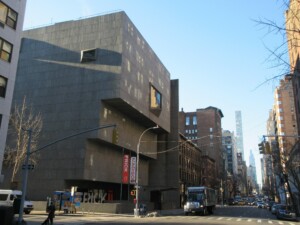

Although Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass is perhaps most famous in the United States for his legendary design collective, Memphis, his life and career involve far, far more, as a fascinating new exhibition at the Met Breuer in New York reveals.

Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, on display through October 8, reevaluates his career in a presentation of works across a broad range of media, including architectural drawings, interiors, furniture, machines, ceramics, glass, jewelry, textiles, painting, and photography. These are presented in juxtaposition with ancient, more modern, and contemporary objects from the museum’s collection, which the museum said places Sottsass “within a broader design discourse.”

Sottsass was born in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1917; his father, Ettore Sottsass Sr., was an architect who trained in the Viennese tradition of the modernist Otto Wagner and his pupils Josef Hoffmann and Kolomon Moser of the Wiener Werkstatte, whose designs influenced the younger Sottsass, the museum said, “with their elegant proportions and spare elegant forms.” Thus, the exhibition’s first gallery features a late 19th/early 20th-century plan for a house by Hoffmann; a 1920 desk set designed by Hoffman and made by the Wiener Werkstatte; Bauhaus textile designs; and a 1903 armchair designed by Moser and Hoffmann, shown with Sottsass’s late 1950s enameled copper round plates and an early 1960s hybrid table/desk/shelf/cabinet/chest of drawers designed for the Mario Tchou residence in Milan.

A section of the exhibition on corporate design discusses the influence of American industrial designer George Nelson on Sottsass: The latter worked in the former’s New York office for a few months in 1956 during Sottsass’s first trip to the United States. According to exhibition curator Christian Larsen, Nelson’s impact can be seen in Sottsass’s early 1970s office furniture for Olivetti and in his 1980s patterns for Memphis. Larsen said that although mass production “allowed for miraculous economies of scale that dramatically provided the latest innovations to the wider public, it also seemed to indicate a culture of rabid consumption sameness and even alienation. Sottsass wrote that he would create ‘tools to slow down the consumption of existence … to curb loneliness and despair.’”

The exhibition also explores Sottsass’s designs for Poltronova, the visionary furniture company. Larsen believes these designs were influenced by everything from ancient Egyptian shabti boxes (containers for a deceased person’s needs in the afterlife, of which one is on display here) to the sculpture of American artist Donald Judd (also on display). Sottsass’s own groundbreaking “Environment,” a system of movable modular cabinets, each containing a different domestic function, proposed for MoMA’s 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, is illustrated with a film made for that exhibition. There is also a section on Sottsass’s ceramics, influenced by his first visit to India in 1961 and a near-death illness in 1962, that features a striking forest of ceramic and earthenware Sottsass totems, one over nine feet tall, and another section devoted to his glass vase designs, some inspired by Native American katsina dolls, on display with ancient Greek and Roman glass and Hopi katsina.

According to Larsen, “despite working on a variety of scales and in an array of mediums, Sottsass always called himself an architect. This vocation informed his fundamental approach to making and living.” To illustrate this, the exhibition features Sottsass’s drawings for the 1986-89 Wolf residence in Ridgeway, Connecticut, which he considered his first mature architectural work, as well as his “paper architecture” Planet as Festival series created in the early 1970s for Casabella magazine.

Clearly, no Sottsass exhibition would be complete without a discussion of his designs for Memphis; this one displays his iconic 1981 “Carlton” room divider and 1985 “Ivory” table alongside other Memphis pieces by Andrea Branzi and Shiro Kuramata.

In an interview last week, Larsen called Sottsass “a bottomless pit of production that will never run dry,” as well as someone whose work “both cut across the grain” and “makes us smile, which is important in today’s charged political times.”