Troy Schumacher is a soloist with New York City Ballet, one of the most prestigious dance companies in the country. And while a job as a full-time athlete might be enough for some people, Schumacher is also the artistic director and choreographer for his own chamber-sized troupe, BalletCollective. All of its members are Schumacher’s fellow dancers at NYCB.

For the company’s latest performance at the New York University Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, Schumacher explored his observations of how human bodies respond to built space. He approached architects James Ramsey, founder of RAAD Studio, and Carlos Arnaiz, founder and principal of CAZA, to collaborate on a project that would turn design into dance. “Last season, I was already sold on the idea of working with architects because I thought our processes would be very similar,” said Schumacher. “Whether you’re creating performance or buildings, you’re thinking about something that has a larger scope but shows details. You’re thinking on two scales.”

Schumacher and his team took care to thoroughly investigate how the two disciplines could come together for a final project. “We discussed how our respective disciplines are organized, how we record our work, how we make changes to our work as we go, and how our respective practices overlap,” said Arnaiz.

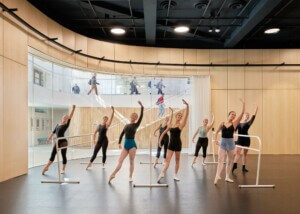

It’s not unusual for architecture and dance to go hand in hand. Just last year, Steven Holl created set pieces for Jessica Lang Dance, while the Guggenheim Museum frequently holds performances in its iconic rotunda. But these dances coexist with built architectural elements—not so for BalletCollective. Instead, Schumacher chose to feature the dancers in a stripped-down environment. The stage at the Skirball center was entirely bare, with curtains lifted to reveal the dancers waiting on the sides, and their costumes were casual rehearsal wear. Until they started moving, there was no indication of the evening’s architectural component.

One of Schumacher’s strengths as a choreographer is his unusual way of using formations. He often asks one dancer to move against the group or pairs a tall woman with a short man. Trios and duets are widely spaced around the stage, playing out contrary to the traditional ballet structure of a principal couple and a shifting background of corps dancers. In Until the Walls Cave In, Ballet Collective dancers moved through lines, boxes or huddles that washed across the stage. Ramsey’s work, in comparison, also carves out space where heretofore there was none. “James’s work is about restoring or facilitating life in a place where it wouldn’t normally exist,” said Schumacher. “We were really driven by light, concrete spaces and the growth happening within them.”

For his part, Ramsey entered the collaboration unsure of what to expect. “I had little to no idea about the creative process for dance,” Ramsey said, “and I was completely blown away by how naturally our processes were able to mesh. Our conversations had to do with the life and death of human spaces, renewal, and the idea of tension as a dramatic architectural design tool.” Here, though, Schumacher might have picked something up from his collaborator. The start-stop energy of his choreography makes it nearly impossible to establish dramatic tension.

Arnaiz’s contribution involved one specific drawing, resulting in The Answer, a duet for Anthony Huxley and Rachel Hutsell. “Choreographers are always looking for new pathways,” said Schumacher. “Carlos emailed us a sketch on top of a photo of Allen Iverson. I was floored by the energy and idea behind it, and we just went with it.” Arnaiz wrote about Iverson in his recent monograph, reflecting on how static geometric forms are brought to life by the creative process of architecture. As a result, The Answer plays off friendly competition.

Huxley is an elegant dancer who, while still able to have fun, is quite serious onstage. Hutsell, who is just beginning her professional career, might be expected to be timid, especially dancing with Huxley (he is several ranks higher than her at NYCB). Instead, she’s remarkably grounded for a woman dancing in pointe shoes, which can complicate quick direction changes and off-balance steps. She eats up space with infectious energy. The dancers’ darting limbs seem to leave trails of lines and spirals across the stage, reminiscent of Arnaiz’s drawing.

Schumacher wasn’t worried about disappointing audiences who might have expected structures or set pieces designed by Ramsey and Arnaiz. “All the artists

who contribute to BalletCollective are a source,” he said. “But invariably, the starting and ending point aren’t the same place. Asking for architectural input is about giving us a place to start.”

Arnaiz and Ramsey were both surprised at what that starting place was able to yield. “I’ve worked with musicians, but never with dancers,” said Arnaiz. “It

was fascinating to see how something transformed from concept to physical performance.” Ramsey agreed: “Troy brought a level of clarity and rationalism

to the projects that was startling, and even led me to understand my own work more succinctly.”

What Comes Next

BalletCollective

The NYU Skirball Center for the Performing Arts

Fall 2017 season to be announced late April.