The situation was dire: People were flocking to cities for work, but scarce land and lack of new construction were driving up rent prices. Middle-income residents couldn’t afford the high-end housing stock, nor did they want to enter cramped—sometimes illegally so—apartments. Luckily, a new housing solution appeared: In exchange for small, single-occupancy units, residents could share amenities—like a restaurant-kitchen, dining area, lounge, and cleaning services—that were possible thanks to economies of scale. Sound familiar?

It should: It’s the basic premise behind Carmel Place, a micro-apartment development in Manhattan’s Kips Bay that recently started leasing. The development—whose 55 units range from 260 to 360 square feet—was the result of Mayor Bloomberg’s 2012 adAPT NYC Competition to find housing solutions for the city’s shortage of one- and two-person apartments. Back then, Carmel Place needed special legal exceptions to be built, but last March the city removed the 400-square-foot minimum on individual units. While density controls mean another all-micro-apartment building is unlikely, only building codes will provide a de facto minimum unit size (somewhere in the upper 200 square foot range). What does this deregulation mean for New York City’s always-turbulent housing market? Will New Yorkers get new, sorely needed housing options or a raw deal?

In a way, this deregulation is a return to an old, widespread, and subsequently outlawed, real estate formula. In New York City at the turn of the 20th century, converting hotels into apartments, and offering single-occupancy units with communal amenities, helped alleviate a housing shortage. These “apartment hotels” were wildly successful until legal changes in 1929 largely eliminated them. Now, it seems, the pendulum of history is swinging back: Carmel Place also offers shared amenities and services through a company named ollie (a wordplay on “all inclusive”). The project’s developer, Monadnock Development, has brought in ollie to facilitate weekly house cleaning, limited butler service, and more, to the building’s 25 market rate units and eight units for veterans with Section 8 vouchers. Those units will also come with space-saving furniture; the other 22 units are affordable but not serviced by ollie.

While micro-apartments haven’t yet proliferated, there is a fundamental economic formula that makes them appealing for developers. It boils down to the difference between rent per square foot and chunk rent. The former is what developers use as a metric for market demand and revenue. The latter is the monthly rent the tenant pays. “Ollie is a sustainable housing model for attainably [sic] priced, high-quality housing, and we’re really exploiting that understanding that the consumer is paying on a chunk rent basis and the developer is driving their model on a dollar per square foot basis,” explained Christopher Bledsoe, ollie’s cofounder. Furthermore, because rent is less a strain on residents’ finances, they become more reliable and long-term tenants.

This dynamic isn’t just conjecture. Before ollie worked on Carmel Place, it renovated and leased micro units in an old Upper West Side building to demonstrate demand for smaller apartments. (The company didn’t offer its standard suite of amenities and services, so the development wasn’t branded “ollie.”) “One of the surprises is that this [micro unit] market is far broader than Millenials,” said Bledsoe. About 30 percent of the building’s renters were over age 34; they included empty nesters, retirees, those seeking to downsize or own pied-a-terres, long distance commuters, and many young couples, not all of whom were Millennials. Units in that building ranged from 178 to 375 square feet; demand was so high rent shot up to around $2,250 for the smallest units, $3,000 for the largest. “Over 40 percent of the tenants coming in [to the Upper West Side micro units] opted for a lease longer than 12 months. That’s huge,” said Bledsoe.

In light of this, Carmel Place is a more mature experiment in micro-living: What combination of amenities, services, and architecture can upend the long-held real estate belief that square footage determines what people will pay? This is where ollie’s pitch comes in: “For every one square foot I can eliminate from the apartment, I can give back $50 a year to the tenant in services,” said Bledsoe. Bledsoe sells ollie as essentially doing two things for renters: First, it leverages its purchasing power to provide economies of scale to its residents. Space-savvy products from Resource Furniture, WiFi, cable, Hello Alfred butler service, housekeeping, and social club membership through Magnises, are folded into the tenant’s rent. Bledsoe argues that those expenses are frequently hidden in rents, so including them helps tenants save time and keep Carmel Place competitive with nearby comparable units.

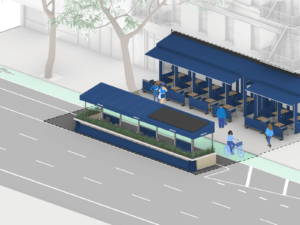

Furthermore, he added, “It’s not just about services and amenities, it’s about the community.” At Carmel Place, a live-in community manager helps arrange social events ranging from BBQs to lectures by guest speakers. While ollie was hired after Carmel Place was designed by New York–based nARCHITECTS, the building’s design facilitated ollie’s mission: Carmel Place features a long, open, “main street” lobby, a ground floor gym, and on the top floor, a communal kitchen, dining area, extensive terrace, and outdoor grills. The walls between the top floor’s private terraces can even be swung aside, creating one giant shared terrace. ollie’s vision for a communal, dorm-like experience also recalls WeLive, WeWork’s coliving experiment (which, unlike a true apartment, doesn’t offer leases beyond 30 days).

Rent at Carmel Place isn’t cheap: At the time of writing this article, unit 6H, furnished and 265 square feet, is going for $2,720 per month. If and when less expensive micro units are built, don’t count on the same quality furniture: Carmel Place’s Resource Furniture can quickly transform a studio into a one bedroom, but it’ll dent your wallet (a standard Carmel Place Resource Furniture setup costs $13,465). If micro-apartments proliferate, isn’t there risk that some won’t be able to afford that kind of hardware? “Yeah, absolutely,” said Frank Dubinsky, vice president at Monadnock Development, who added that, “In the future what will likely happen is there needs to be more furniture out there that works in these spaces. Resource’s stuff is great but it’s not inexpensive.” And what about affordable housing—will the next generation of New York’s affordable units be bare, 260 square foot apartments?

Thankfully, on that count, no. When it comes to the city’s new MIH (Mandatory Inclusionary Housing) program, where developers must set aside 20 percent to 30 percent of a residential building’s floor areas for affordable housing, an affordable studio can’t be less than 400 square feet and an affordable one-bedroom can’t be less than 575 square feet. Furthermore, the mix of affordable unit types (studios, one-bedrooms, etc.) must match the ratio of market rate units. Combined with density controls, it’s very unlikely a residential building would use all its floor area for micro-apartments. MIH policies are currently only in effect in the recently rezoned East New York neighborhood but, overall, the program is a major part of the de Blasio administration’s plans to build or preserve 200,000 affordable units over the next decade.

There’s also the unpredictable law of supply and demand to consider. California may offer some insight: In the 1980s, in a push to increase affordable housing stock, San Diego passed a legislation to allow micro-apartments. The practice subsequently spread to L.A., San Francisco, and beyond. “To a certain extent, you have to let people vote with they wallets,” said David Baker of San Francisco–based David Baker Architects. Baker’s firm recently designed an upscale condominium development in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley; half of its 69 units are micro-apartments. “If it doesn’t rent, people won’t build them. If you have more competition, they’ll be better and rent for less.” Monadnock and nARCHITECTS created voluminous, bright, airy interiors for Carmel Place units. “Those things are not required by the zoning code—tall ceilings and big windows—but I think they’re part and parcel with this becoming a replicable typology in New York City,” said Dubinsky. Only time will tell if New Yorkers avoid less generous micro-units, a fact that isn’t heartening to those were excited to see so many innovative housing solutions—including a full-scale, Resource Furniture-equipped micro-apartment interior—at the 2013 exhibition Making Room: New Models for Housing New Yorkers at the Museum of the City of New York. Perhaps mid-tier micro-apartments will appear, along with lower cost furniture to match.

Conversely, there’s the possibility that micro-apartments will remain a niche market in select cities where housing stock is short and a few urbanites will trade “space for place.” “At present, and for the foreseeable future, micro units are such a small segment of the new multi-family housing supply that’s coming online in cities that it’s highly unlikely they’re going to have any material impact on rent,” said Stockton Williams, executive director of the Terwilliger Center for Housing at the Washington, D.C.–based Urban Land Institute (ULI). But in terms of how micro-housing is already evolving, ollie’s next two projects, one East Coast, one West Coast, may presage what form it’ll take.

The first, in Long Island City, is 42 stories. Floors two through 15 will contain 426 ollie-served micro-apartments. They’ll have the same basic suite of amenities found at Carmel Place (Resource Furniture, WiFi, Hello Alfred, etc.). However, the conventional apartments can also opt into ollie’s services. The second development, in downtown Los Angeles, involves—in a twist of historical irony—a hotel. Located on a 192,000-square-foot site, the project will feature 30,000 square feet of amenities and retail. The 300 ollie micro-apartments will have access to the hotel’s amenities: “Rooftop pool, gym, lounge spaces, food and beverage, essentially what you’d expect to find in a trendy hotel amenities program,” said Bledsoe. “We’re even talking about putting recording studios in the basement, doing some fun things that are more local.” Some of the micro-units will actually be micro suites (micro-units with a shared bathroom and kitchen), a model that a 2014 ULI report identified as being even more profitable for the developer.

Maybe cities will find new reasons to dislike micro-apartments—when cities emptied in the 70s, their Single Room Occupancy (SRO) developments deteriorated, became stigmatized, and were vastly cut back. But this time around, there’s growing awareness among developers that communal living is marketable and desired by tenants. “For a lot of people home is the happy place, but more home doesn’t equal more happy. I think more home equals more money and more maintenance,” said Bledsoe. But the exploration of micro-apartments’ future is just beginning. As Baker explained, they’re popular among seniors, not only for being cheaper, but simply “It’s a lot less to clean… and they want the bathroom to be closer.” Seniors’ micro-apartments with rooftop shuffleboard? Middle-class micro-apartments paired with a Motel 6? Who knows. But if the micro-apartment does indeed take this many forms, maybe the pendulum of history won’t know which way to swing.