The fabric of New York—from shoreline to skyline—is getting a thread-count upgrade, much of it due to the success of ongoing projects like Vision Zero, coastal resiliency efforts, and a spate of new public ventures coming down the pike. In his annual State of the City address in early February, Mayor Bill de Blasio championed accomplishments from 2015 and shed light on what’s to come: New Yorkers will see projects and policies that could facilitate new commutes, provide civic and green spaces in the outer boroughs, and reshape neighborhood density via rezoning.

Streets and Shores

Two large-scale, controversial rezoning proposals, Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) and Zoning For Quality and Affordability (ZQA), reached the City Council early February. Councilmembers heard public testimony for and against the measures, which are intended to increase the amount of affordable housing and create more interesting streetscapes in exchange for increased density in special districts. The full Council will vote on the proposals—the most sweeping zoning changes since 1961—in March.

The initiative is New York City’s version of an international campaign to end traffic-related deaths through better street design and harsher penalties for traffic offenders, and it has a record-setting $115 million budget for 2016. More than a quarter of that money (plus $8.8 million from the NYC Department of Transportation’s capital budget) will go to road improvements in Hunters Point in Long Island City, Queens, especially at busy nodes along main thoroughfares Vernon Boulevard and Jackson Avenue.

The low-lying neighborhoods are some of many flood-prone areas that will benefit from the $20 billion in climate-change-resiliency measures that launched following Hurricane Sandy. Included in that figure is a massive project coming out of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rebuild by Design competition to protect Manhattan from rising seas. The City has selected AECOM to lead the design and build of these coastal resiliency measures, formerly known as the Dryline (and before that, BIG U). The project team includes Dewberry, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and ONE Architecture. BIG and ONE provided the original vision for the 10-mile-long project, and are now working on Phase One, the $335 million East Side Coastal Resiliency Project. That phase, which should go into constriction next year, deploys a series of berms and floodwalls from East 23rd Street to Montgomery Street on the island’s Lower East Side. Phase Two extends the project from Montgomery Street around the tip of Manhattan up to Harrison Street in Tribeca.

Although those ten miles of coastline could be safer, the other 510 would still have a lot to fear from global warming. Fortunately, the Department of Design and Construction’s Build It Back RFP is having an immediate impact on those who lost homes to Sandy. By last October, the program, which rebuilds homes ravaged in the 2012 hurricane, broke ground on around 1,900 projects and finished construction on 1,200 others.

Targeted Reinvestment

The recovery impetus extends beyond the property line and out into neighborhoods. In his speech, the mayor singled out three outer-borough neighborhoods—Ocean Hill–Brownsville, the South Bronx, and Far Rockaway—for targeted reinvestment. Civic architecture often heralds or spurs financial interest, and these neighborhoods happen to be the sites of three public projects by well-known architects in plan or under construction. Studio Gang is designing a 20,000-square-foot Fire Department of New York station and training facility in Ocean Hill–Brownsville in Brooklyn, while BIG is designing a new NYPD station house in Melrose in the Bronx.

In Queens, far-out Far Rockaway, battered by Sandy and isolated from the rest of the city by a long ride on the A train, is anticipating both a $90.3 million, Snøhetta-designed public library and $91 million in capital funds for improvements in its downtown on main commercial roads like Beach 20th Street.

On and Beyond the Waterfront

In New York, a trip to the “city” is a trip to Manhattan. This idea, however, doesn’t reflect how New Yorkers traverse the city today: Older, Manhattan-centric commuting patterns at the hub are becoming outmoded as development intensifies in the outer boroughs.

It’s estimated that this year bike-sharing service Citi Bike will have 10 million rides. The system is adding 2,500 bikes in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens to accommodate the increased ridership. The East River ferry service will begin this year, knitting the Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan waterfronts together in patterns not seen since the 1800s.

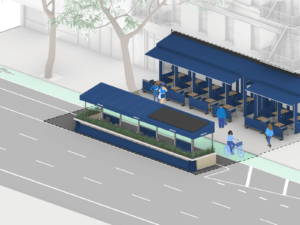

Along the same waterway, the project that’s raised the most wonder (and ire) is the Brooklyn-Queens Connector (BQX), a streetcar line that would link 12 waterfront neighborhoods from Sunset Park, Brooklyn, to Astoria, Queens.

The project proposal comes from a new nonprofit, Friends of the Brooklyn-Queens Connector (FBQX), which first surfaced in January of this year. Its founders include the heads of transportation advocacy and policy groups Regional Plan Association and Transportation Alternatives; directors of neighborhood development groups; and real estate professionals like venture capitalist Fred Wilson and Helena Durst of the Durst Organization.

The full plan, commissioned by FBQX and put together by consultants at New York–based engineering and transportation firm Sam Schwartz, is not available to the public, although the company’s eponymous president and CEO shed some light on the plan with AN.

“Within an area that has so many [transit] connections, what we are addressing is transit that goes north–south,” explained Schwartz. His firm’s plan calls for a 17-mile route that roughly parallels the coastline, dipping inland to link up to hubs like Atlantic Terminal and the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

At a projected cost of $1.7 billion, why not choose the bus, or bus rapid transit (BRT)? The team considered five other options before deciding on the streetcar, Schwartz explained. “The projected ridership is over 50,000 [passengers] per day, while ridership for the bus and BRT maxes out at 35,000 to 40,000 per day.” Streetcars, Schwartz elaborated, can make fine turns on narrow streets, reducing the risk for accidents. They will travel at 12 miles per hour in lanes separate from other traffic, and, to minimize aesthetic offense and flood-damage risk, overhead catenaries will not be used.

Norvell stated that the city’s plan calls for a $2.5 billion, 16-mile corridor that will be financed outside of the auspices of the (state-funded and perpetually cash-strapped) Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) using a value-capture model. The streetcar line’s success, essentially, is predicated on its ability to raise surrounding property values. The increased tax revenues, he explained, could be plowed back into a local development corporation, which would then use the funds to capitalize the project.

Critics wonder why the streetcar is being privileged over other initiatives, such as the Triboro RX proposal, a Utica Avenue subway extension, and the not-completely-funded Second Avenue subway, that would serve more straphangers. Though a fare-sharing system could be brokered with the MTA to enhance multimodal connectivity, critics point out that the streetcar line’s proposed stops are up to a half mile from subway stations, bypassing vital connections between the J/M/Z and L.

The Hills on Governors Island Are Alive and Ahead of Schedule

With a growing population and growing need for more parks, the city is looking to develop underutilized green space within its borders. The Hills, a landscape on Governors Island designed by West 8 and Mathews Nielsen, is set to finish nearly one year ahead of schedule.

The news coincided with the mayor’s announcement that the island, a former military base and U.S. Coast Guard station, will now be open to the public year-round. The city has invested $307 million in capital improvements to ready 150 acres of the island for its full public debut. Forty-eight new acres of parkland (including the Hills) will open this year.

The Innovation Cluster, a 33-acre business incubator and educational facility that builds on the example of Cornell University’s campus extension on Roosevelt Island, will bring several million new square feet of educational, commercial, cultural, research, and retail space to the island’s south side.

The Trust for Governors Island, a nonprofit dedicated to stewarding and capitalizing on the island’s assets, will release an RFP to develop the vacant land and historic district by the end of this year, and construction could begin as early as 2019.