Ost Und oder West [East and West], Klaus Wittkugel

P! Gallery

Ended February 21

How does one do good work for bad people? This oversimplified question is especially relevant for architects, and one that the recent exhibition of work by East German graphic designer Klaus Wittkugel at P! Gallery asked us to consider, while simultaneously while treating us to some modernist visual pleasure.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall we have been taught that capitalism is the end-all-be-all system to structure our society, and consumption is the answer to our desires, overwhelmingly influencing our aesthetics and our ethics. But looking at the oeuvre of this little-known figure, Klaus Wittkugel, who was the head designer of the German Democratic Republic’s Socialist Ministry of Information, we find an alternate reality: a sense of aesthetic purpose that, while firmly modernist, shows a softer, more figurative and less abstract approach to design. And yet at times it can be reminiscent of Socialist Realism propaganda, today usually met with finger wagging and dismissals of kitsch: the prefered visuals of dictators, with smiles beaming sunshine and 150 percent worker productivity embodied in a visual image. Yet what this show, Ost Und oder West [East and West], revealed is a more complex relationship between design and power, and the extent of artistic freedom under Soviet Communism in postwar Germany.

The exhibition is not only impressive for the work it contains, but also for how it was assembled. P! founder and director, Prem Krishnamurthy, spent more than seven years assembling Wittkugel’s work into a thorough survey of books, posters, exhibitions, and signage, found in auspicious moments at used bookstores and by scouring eBay.

The work of Wittkugel displayed in the gallery was in a visual style that positions him as an heir to the legacies of early 20th Century design legends El Lissitzky and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, like a long-lost East German cousin of the earlier German Bauhaus and Russian Constructivist diasporas. The judicious use of mis-en-abyme—the graphic technique of creating an infinity mirror, a recursive visual trick of an image containing a smaller version of itself in a window in a window in a window in a…—we might describe today as being very “meta.”

Krishnamurthy acknowledges that “one of the things that really attracted me to his work is there’s a strain of self-reflexivity about the production of graphic design. So you have a poster, for an exhibition of posters, that is a freshly-postered poster column,” which the P! exhibition continued, recreating the poster column on the gallery facade.

All of this is juxtaposed with a companion exhibition at OSMOS Gallery on the work of Anton Stankowski, a former classmate of Wittkugel’s from the Folkwangschule Essen, who went on to work in West Germany and Zurich, designing many corporate logos, most notably the minimal Deutsche Bank slash-in-square, still in use today. While Stankowski designed symbols of Western capital, Wittkugel designed the visual manifestation of the political and cultural ambitions of Soviet East Germany in the form of an elegantly embellished cursive visual identity, dinnerware, and signage for the now-demolished Palast der Republik.

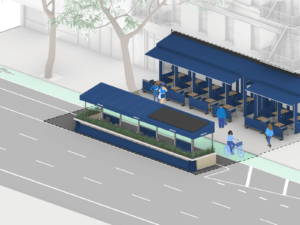

While works like Wittkugel’s signage for the Kino International relate more literally to architecture, the conceptual lessons the exhibition has for architectural practice speak more to architecture’s inevitable collaborations with people whose values may not align with one’s own. You can refrain from designing prisons if you object to incarceration, but it doesn’t mean some architect somewhere won’t design that prison, so why not engage and attempt to design a more humane prison? The importance of critical engagement is shown in Wittkugel’s 1957 exhibition Militarism without Masks, a polemical, anti-West German exhibition featuring former Nazis who became part of the West German government, displayed on a cleverly designed rotating vertical triangular louvered wall, just one example of very compelling exhibition design.

Any serious international cultural institution would be remiss not to consider exhibiting, or even adopting, this collection of thought-provoking work from a precarious moment in design history.