There’s been no shortage of worthy architectural documentaries in recent years, but you’ll want to make room on your DVD rack for the latest look at a major American figure: Louis Sullivan: The Struggle for American Architecture. Recently given its New York premiere courtesy of the good people at Docomomo New York/Tri-State, this touching and tragic film offers a portrait of the man who perhaps more than anyone aspired to create an American style of architecture, yet was left behind by a nation on the cusp of a century that Sullivan himself did much to define.

First-time director Mark Richard Smith frames Sullivan’s story as a battle between the architect’s original vision—one explicitly crafted as an expression of American democracy—and historicist styles imported from Europe that would sweep the nation in the late 19th century. The latter are embodied by Sullivan’s Chicago archrival Daniel Burnham, whose triumph at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893—where the sprawling White City was an ode to Beaux-Arts classicism—drove the nail in the coffin of modern experimentation, and, as Sullivan bitterly remarked, was the place where “architecture died.”

Even for devotees of Sullivan’s astonishing output, the details of his life are not well known, and the film puts his career in the context of a Chicago surging from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871, the “Katrina of its day” that created huge opportunities for architects. Into this boom stepped Dankmar Adler, a renowned acoustician but lackluster designer who saw just the creative spark his firm needed in a young Louis Sullivan. Adler & Sullivan would design landmarks such as Chicago’s Auditorium of 1889, taking cues from H.H. Richardson’s brawny Romanesque but leavening it with Sullivan’s unusual decorative programs. When Frank Lloyd Wright joined the team as chief draftsman, one of the great ensembles in architecture was born. (The firm’s work is chronicled in the recent Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan, another must-have volume for Chicago architecture aficionados.)

The film, itself just released on DVD, taps experts like City University’s Robert Twombly and Chicago historian Tim Samuelson to add depth to Sullivan’s story, including the major innovations marked by his early skyscrapers. Of seven tall buildings he managed to complete, five are left, and the influence those few structures would have on American architecture, with their emphasis on verticality and functional design, is the architect’s last word over his historicist contemporaries. It wasn’t the later Mies or Corb, of course, but Sullivan who coined the phrase that would define the century to come: “form ever follows function.”

Nearly all of Sullivan’s major surviving buildings are gorgeously photographed here, with close-up pans across the upper reaches of Buffalo’s Guaranty Building and inside the Auditorium, for example, revealing ornamental details hardly visible from below. Among the discoveries of his late career is a string of one-off bank buildings in small midwestern towns that are delicate masterpieces made by a man who knew history had left him for dead.

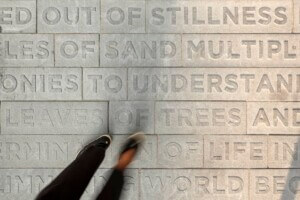

Chronicling the last years of Sullivan’s life, during which the destitute designer was forced to sell his personal effects at auction, the film pauses over a devastating note inscribed on a drawing made as Sullivan sat in borrowed quarters to compose a primer on ornament. As if reaching back to the inspirational wellspring of his youth, Sullivan writes: “Remember the seed-germ.”

For the architecture-obsessed, this is spine-tingling stuff. Louis Sullivan may not pack the psychodrama of Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect, but its close focus on the buildings themselves makes it equally affecting. By the end of this journey through the rafters and across the cornices of a great architect’s career, you feel the film’s sweeping subtitle—the struggle for American architecture—just about hits the mark.