Puncturing the myth of progress has become a preoccupation of contemporary cinema. Regression offers far more interesting material to mine, if the latest adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune is any indication.

The story is set over 10,000 years in the future, and mankind has lapsed into a neofeudalistic social order ruled by a galactic emperor. Great houses jockey for power across solar systems. The lynchpin of the empire is Arrakis, a desert planet that’s the only known source of a powerful drug known as spice. Consuming it extends the life of the user and enhances everything from awareness to prescience; in large enough doses, its effect becomes ridiculously potent, enabling faster-than-light travel through the folding of space. Arrakis is also home to the Fremen, religious refugees under the thumb of House Harkonnen, the planet’s spice-mining overseers; 700-mile-per-hour sand storms; and most notably, the sandworms—leviathans that stream through the desert like unbounded rivers, each large enough to swallow a skyscraper.

Directed by Denis Villeneuve, the film hews closely to the first half of Herbert’s 1965 novel. Things kick off after Duke Leto (Oscar Isaac) of House Atreides is ordered by imperial decree to take over the mining operations on Arrakis, which he does full well knowing it is a trap. Taking along his concubine Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) and son Paul (Timothée Chalamet), things quickly go awry.

All of this is played dead serious, as Villeneuve steers clear of quips or undercutting the emotional moments as they unfold. At two-and-a-half hours long, the film more than matches the dramatic sweep of the source material while dispensing with much of the palace intrigue of the novel and marathon exposition that bogged down David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation. Dune is a space opera progenitor that goes to psychedelic places, but Villeneuve’s take is nonetheless grounded in a “reality,” production designer Patrice Vermette told AN.

“One thing that is extremely important for Denis is to anchor things in something that will look plausible,” Vermette said of his frequent collaborator and fellow French Canadian. (The two previously worked together on Prisoners, Enemy, Sicario, and Arrival.) Similar to how the look of 2016’s Arrival was realized, Vermette noted “He’s got a documentary aspect, like style of filmmaking, and the thought there is they need it to look real.”

Despite their awe-inspiring size, the buildings that populate the Dune galaxy have a certain tactility. Vermette attributes this quality to an insistence on using physical sets, some maxing out at 24 feet tall. Fabric that matched the scene’s lighting was used to block out past the upper registers of these towering structures, allowing Villeneuve to better direct the performers before the requisite CGI was added. All three of the film’s cavernous, stark palace interiors—the Atreides castle on Caladan; the desert fortress at the heart of Arrakeen on Arrakis; and Giedi Prime, lair of antagonists House Harkonnen—were constructed at Origo Studios in Budapest. The palace designs, although united in their use of concrete that’s often weeping at the joints in disrepair and looks at the end of its life, uniquely respond to the environments of their host planets.

To nail the look of a galactic humanity thousands of years from now, Vermette drew from a wide variety of sources.

“The inspiration came from ziggurat architecture, from bunkers. I looked at a lot of World War II bunkers,” mused Vermette when asked to name specific architectural references. “Obviously Brutalist architecture, but mostly Brazilian Brutalist architecture, because I find the lines interesting. I also found the massive structures of Superstudio from the ’60s and ’70s to be extremely inspiring. When you read the book, there’s the sense of scale, and when you look at the work of Superstudio, it’s [from] the same era. It’s the same psychedelic concepts.”

Much of Dune’s appeal is the way it blends historical references into a mostly coherent whole. The medieval elements of Herbert’s story are impossible to miss, Vermette noted, but rather than borrow from Gothic cathedrals and crypts, he instead looked to old Japanese architecture for reference. The design of Caladan in particular, with its ruined, autumnal environs modeled after coastal Canada, connotes a civilization quietly sliding into obsolescence. “In the early conversations that I had with Denis,” recalled Vermette, “the idea was to convey the idea of something that is ending, like a tradition that is going to fade away. It’s a passage to something else.”

That passage is literalized in the plot, when Duke Leto, Jessica, and chief protagonist Paul depart for Arrakis, also known as Dune. Taking its leave of Caladan, the film widens in scope, luxuriating in Arrakis’s sandy vistas and the capital stronghold of Arrakeen, which represents the apex of humanity’s architectonic ambitions. Vermette’s ziggurat research clearly shines through here, with the stepped slopes of the central fortress, the largest ever built by humanity, intended to allow the powerful winds to pass over. It stands in stark contrast to the sinuous and ever-changing desert beyond, a clear monument to the strength of the planet’s colonizers. Even the desert was real; the scenes of the scorched Arrakis beyond the city’s thick walls were shot in Abu Dhabi, while the rock formations were in Jordan.

“You would need to build something that is super thick to keep [it] cool inside and never any direct sunlight because the sun could kill you,” said Vermette, observing Arrakeen’s would-be building practices. “So, we created this system of light wells to distribute the light inside the palace. And that’s what’s creating the shadows and the more-or-less lit areas. But there’s very little direct sunlight.”

Aside from the palace’s role as a monument to empire, it also serves to dwarf Paul and underscores how insignificant he is at the start of the story. Scale is employed throughout the film as an important storytelling mechanism—first to demonstrate the Great Houses’ ability to manipulate the environment to extravagant ends, and after the audience has become habituated to the universe, to demonstrate just how frail humanity’s achievements are in the face of colossal sandworms. The message is clear: Nature always wins in the end.

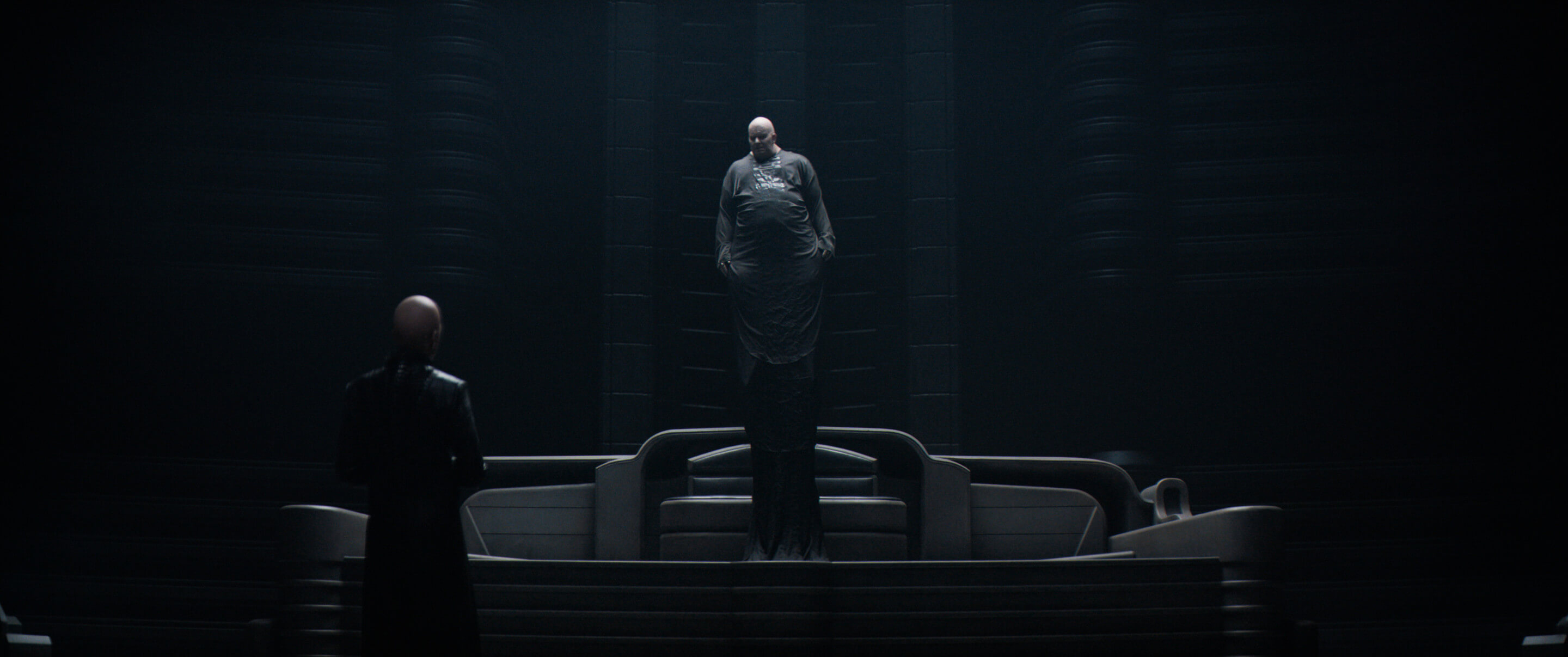

Scale is used in other effective ways, especially to signal the motives of characters like Baron Harkonnen, the villainous mastermind of the plot against House Atreides. In an early meeting between the Baron and a representative from the shadowy power behind the throne, the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, he appears in his concrete throne room ensconced in a cone of light resembling an Anthony McCall installation. Every inch of the room is banded by stone ribbing, and at the scene’s end, the Baron activates his anti-gravity mobility aid and rises to the ceiling, an effective metaphor for the looming threat his house presents.

“That chamber needed to be like a church,” explained Vermette. “All of the ribs inside of that chamber were inspired by John Portman’s architecture. When I was 11 years old, my parents and my family, we went on a trip and I remembered staying at the Hyatt Regency in San Francisco. And I was looking up and it was all these tiers that looked like ribs, as if you were inside a whale. That old memory came back to me when I was working on [Giedi Prime].”

(Portman’s architecture has proven increasingly popular in science fiction productions in recent years; this past summer the interiors of the Atlanta Marriott Marquis served as the digs for the Time Variance Authority in Disney’s Loki series. Vermette, however, emphasized the horizontal plane rather than reaching for soaring heights.)

Like Vermette, Villeneuve’s devotion to Dune dates to his youth. Not long after reading the book as a teen, said Vermette, the future director prepared a storyboard for a film adaptation at 13 or 14. Lynch’s film, starring Kyle MacLachlan in the role of Paul, debuted only a couple years later. Villeneuve intentionally sought to distance the new version from the earlier attempt. Savaged by critics and fans alike, Lynch’s effort has been panned as simultaneously confusing and overstuffed with exposition, but is still notable for its ornate sets, often bordering on Baroque, painterly sensibilities, and grotesque creature designs.

“We did stay consciously away from that Dune,” said Vermette. “We wanted to start with a clean slate because it’s not a remake. It’s Denis’ vision. Although, I have to say that I did like the design of Lynch’s movie.

“This is a movie in the history of science fiction that we were like, okay, there’s obviously 2001: A Space Odyssey, then Star Wars, but Dune is one of them. Tron is another one that visually you’re like, okay, we’re going somewhere else. There’s the before and after.”

As for the giant sandworms that are arguably Dune’s most iconic image, they, and the intrinsic role they play in the Fremen religion, had to come across as appropriately powerful on the screen.

“We explored many avenues for the worm,” explained Vermette. “But in the end, we wanted the worm not to be a scary monster. We wanted it to be more than that—more like a godlike figure that commands respect. It’s an old creator, something that has some sort of an internal wisdom in its own sense. So, the skin is scratched a bit, like roots.” He and Villeneuve pondered the ramifications such a creature would have on its environment, so “when you fly over Arrakis, you could actually see depressions that mark the passage of a sandworm,” Vermette said.

Dune: Part One, which is still in theaters and streaming on HBO Max, met with near-instant box office success despite its split release strategy. An October 2023 release date has already been set for Part Two. Part One went to some strange places; expect the sequel to be even weirder.