Open for only a month, from October 22nd through November 20th, the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial was a quick look at an extremely expanded understanding of design. Far from a trade show of the latest in design objects or material innovations, Are We Human? The Design of the Species 2 seconds, 2 days, 2 years, 200 years, 200,000 years explored the relationship between what it is to design and what it means to be human. In order to provoke a response to this instigation, co-curators Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley set out eight interlinked propositions to which the participating 250 designers, architects, scholars, and scientists reacted:

- Design is always design of the human

- The Human is the designing animal

- Our species is completely suspended in endless layers of design

- Design radically expands human capability

- Design routinely constructs radical inequalities

- Design is even the design of neglect

- “Good Design” is an anesthetic

- Design without anesthetic asks urgent questions about our humanity

These propositions set up a standing provocation: What defines a human is the act of design. The resulting show investigated this claim, presenting evidence in support of, and questioning of, these eight statements. The array of work ranged from very physical infrastructures of resources, power, and movement around the world, to the ephemeral space of social media. The show specifically rejected the construct of looking at the immediate past and future, usually two years before and after a biennial, and instead looked back to the beginning of humanity and the path to its current state.

The defined understanding of design presented by the show was nothing less than extreme in its scope, temporally and ideologically. The work of the participants was divided into four overlapping “clouds”: Designing the Body, Designing the Planet, Designing Life, and Designing Time. Together the show strove to present a worldview in which humans were at once defined by and inseparable from the things they design.

In many cases, the curators and participants would not have to look far to find evidence to support their many investigations. Istanbul itself was leveraged repeatedly to enforce the narrative of the show. In one striking exhibit, a cast of hundreds of footprints, recently found during a subway excavation in the city, shows evidence of Neolithic humans ritually gathering in large groups, while all wearing shoes. A room away, a dance floor produced a space that highlights the much-misunderstood world of the Köçek, a sexually ambiguous class of dancers from Turkey’s recent history. In both cases, clothing was presented as an augmentation for either utility or performance, expanding the definition of the human condition. Such investigations continued through the show, looking into the human body and to its immediate relationship to the world.

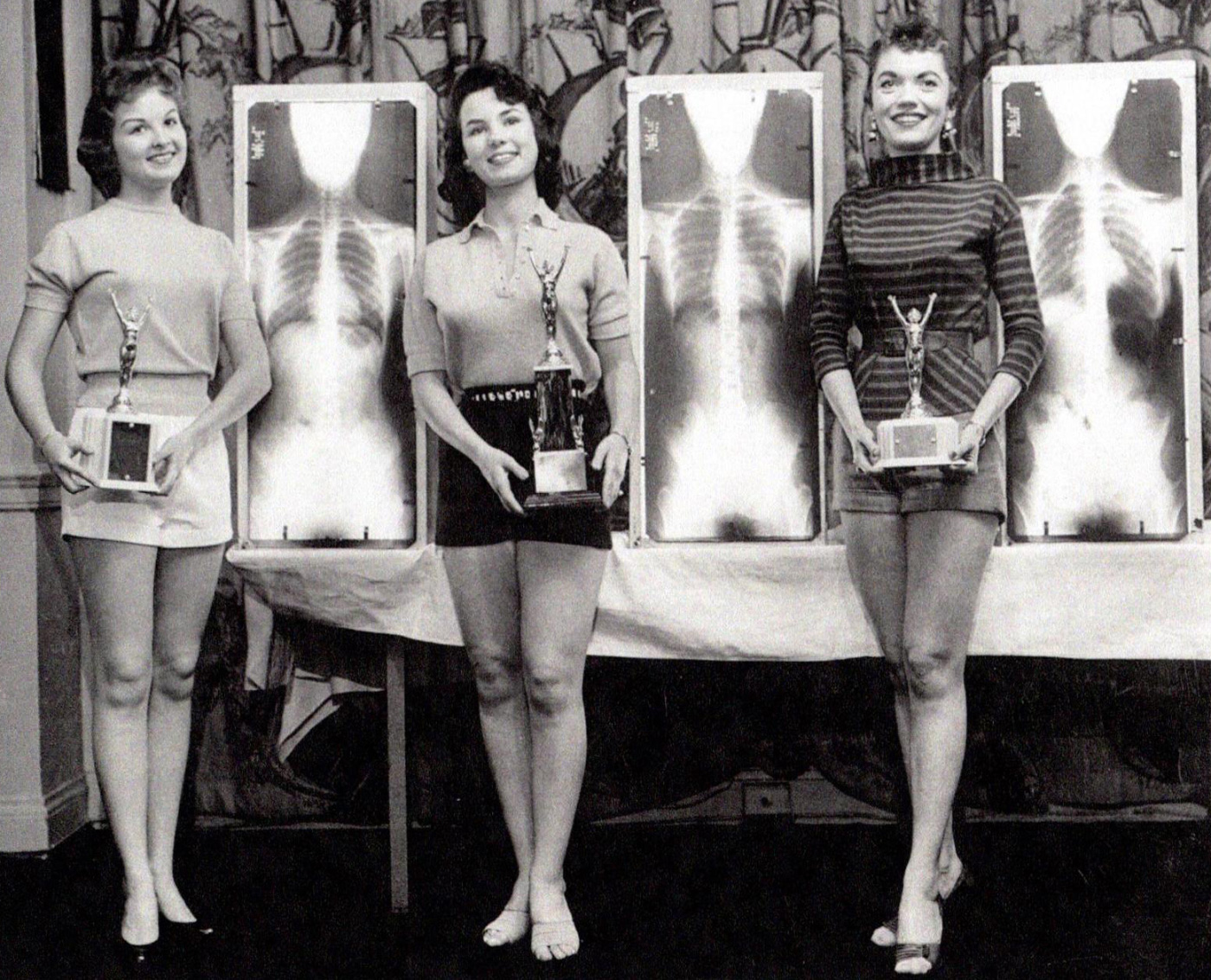

Over and over throughout the Biennial, the idea of human existence was defined by endless layers of design. Prosthetics, complex neural maps, medical pedagogy, and the body of Olympic athletes all highlighted the direct and indirect indications of design’s relationship to the human body. Turkish gravestones, atomic testing sites, oil production infrastructure, and geopolitical gerrymandering, questioned society’s—and design’s—relationship to the planet as a whole.

As a whole, the Biennial felt neither cynical nor optimistic. Rather, it built an image of the world that, for good or for bad, was a construct of humanity. This image was less about dividing the world into artificial or natural, or destructive or constructive. Instead, it illuminated a world of facts and situations, each intertwined with a definition of what it means to be human. Often invoking the concept of the Anthropocene, the proposed geological age in which humans are the dominant influence on the world’s environment and climate, the show was unflinching in laying out a case for humans’ role in shaping every aspect of the world we live in.

By broadening the topic and scope of the Biennial, Colomina and Wigley, admittedly, were attempting to questions the very role of all biennials. With the proliferation of biennials and triennials around the word, each one is undoubtedly compared to every other. The breadth of this show’s topic set it in opposition those with very specific investigations as well as those events with loose or ambiguous themes. Yet despite the seemingly expansive vision of this show, its tightly curated thematic prompts and Andres Jaque’s subtle exhibition design held it together. The result was a biennial that allowed visitors to focus on whether they agreed or disagreed with the show’s premise, rather than trying to figure out what the show was even about.

A note must also be said about who actually went to this exhibition. While many biennials may attract a majority of visitors from around the world (but within the design field), Istanbul was decidedly attended by locals. The organizers and the curators knew well that the Istanbul Design Biennial, this being the third iteration, is mostly attended by Turkish residents. The country’s recent political situation has only exasperated this point. Some estimates put Turkey’s tourism numbers down by over 30% in the past year. At the same time, Turkey has taken on more than 2.5 million refugees from Syria. And though it may be hard to quantify exactly who is coming to the show, these facts felt somewhat fitting as part of Are We Human? The thoughts of shifting populations, global economic and political systems, all enforced the thesis of the unrelenting impact of humans on the world as a whole.

While short in length, Are We Human? The Design of the Species 2 seconds, 2 days, 2 years, 200 years, 200,000 years, was big on vision. By just asking “are we human?” it opened up a dialogue that could be as short as “yes” or considerably protracted. In either case, it put forward that the key to any discussion of this topic is a relationship to, and the act of, design. In effect, it raised the discourse of design above mere products and objects while grounding it in the very fabric of humanity.