“The city must completely disappear from the surface of the earth and serve only as a transport station for the Wehrmacht. No stone can remain standing. Every building must be razed to its foundation,” said SS chief Heinrich Himmler, referring to the Polish city of Warsaw in 1944.

When Warsaw was systematically flattened by the Nazi party in World War II, an estimated 85-90 percent of buildings, including the 18th Century Old Town, were destroyed. Such was the state of decimation that post-war town planners had to refer to 18th century paintings of the city by Italian artists Marcello Bacciarelli and Bernardo Bellotto to aid its reconstruction.

Despite infighting between planners, some of whom wanted to use the clean slate to radically modernize the city, and with minimal help from neighboring states, the citizens of Warsaw rebuilt the city.

Now, the reconstructed Old Town of Warsaw is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but what does this say about the role of architectural preservation and authenticity?

In light of ISIS’s path of destruction, which has seen the loss of architectural treasures across the Middle East, many are already seeking ways to restore monuments that have been destroyed. And similar questions about authenticity are entering broad public discourse.

The 1,800-year-old Arch of Triumph in Palmyra, Syria is one of the latest ancient monuments to be toppled by ISIS. However, Oxford’s Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA), had other ideas about its fate. The team, spearheaded by director Roger Michel, has faithfully remade a facsimile of the arch.

Using marble donated from Egypt, 3D modeling tools, and photographs of the original Roman arch, the Arch of Triumph has been reconstructed in London’s Trafalgar Square. Here it resided for only 3 days before touring the world, due in New York this September.

The Arch’s restoration, however, has sparked a debate on whether we should restore such monuments.

“History would never forgive us” writes Jonathan Jones in the Guardian, who says that ISIS’s destruction should remain as a reminder of the horror they inflicted on the city and the Middle East. The Arch has also been hailed as “unethical” and a “reconstruction of ‘Disneyland’ archaeology.” Indeed, it is worth noting that few people were aware of Palmyra before ISIS stormed in and ‘put it on the map’ so to speak (albeit in the most sinister of fashion).

Michel, on the other hand, argues “Monuments—as embodiments of history, religion, art, and science—are significant and complex repositories of cultural narratives. No one should consider for one second giving terrorists the power to delete such objects from our collective cultural record.” He also adds: “No one would have seriously considered leaving London in ruins after the blitz.”

Jones, however, counters that “Palmyra was in ruins before ISIS occupied it and it is still in ruins today.” Yet the Palmyra ruins, before ISIS came along, were already a World Heritage Site.

With regards to Michel’s comment on the Blitz, the Marshall plan aided London and other major cities, however, the world didn’t donate to Brest, Dresden, Coventry, and Croydon when they were bombed. Admittedly, these cities all belonged to world powers, but historical buildings nonetheless were still lost.

What’s interesting in Britain is how post-war architecture is now cherished, with many brutalist structures being nationally listed. The case of Coventry and its Cathedral is a poignant example. Such was the decimation of the city that Luftwaffe coined the phrased “to coventrate.” As a result, the city’s 14th Century cathedral was blown out, but its successor, built by Basil Spence and Arup is now a Grade 1 Listed Building — the highest level of protection grantable.

Here, a new history has been born. But should Palmyra be awarded the same respect? Or does the age of its ancient ruins nullify this?

A lesson on how not to rebuild history can be seen in Skopje, Macedonia. The baroque and neo-classical buildings, part of “Skopje 2014” (completed in 2015) constructed in the last six years create an altogether alienating experience. Seen by many as an attempt to rewrite history through architecture, the project tries to paint over the built monuments of its socialist and Yugoslavian past and has consequently been cloaked in controversy.

Here the existing architectural dialogue has been lost among the myriad of misplaced nostalgia. Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski’s taste for baroque neo-classical facadism and obsession with classical history has resulted in seemingly satirical postmodern architecture, typified by a “laughable” statue of Alexander the Great. Suffice to say, Skopje is not a world heritage site.

As for Palmyra though, the scale of restoration is another point of discussion, as is who’s duty it is to rebuild it. If the stamp of being a UNESCO World Heritage Site is any barometer to abide by, then Warsaw sets a precedent in that reconstruction does little to alter authenticity. As to who should undertake the restoration, however, remains open.

Simon Jenkins, chairman of England Wales and Northern Ireland’s National Trust asks “How much of what has gone should be restored? By what means, and by whom? And where does Palmyra belong, to Syria or the world?” In a globalized era, does the status of being a piece “world” heritage signify global ownership and responsibility?

Politics has also plagued the issue: former London Mayor Boris Johnson has backed Michel and demanded that “British archaeologists be in the forefront of the project,” especially considering how “ineffective” Britain was in safeguarding the site originally. And so leading the way, for now at least, is Oxford’s Institute for Digital Archaeology. However, they aren’t the only conservation group to go digital.

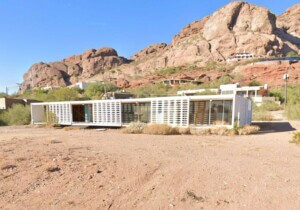

Taking a different approach, yet still using technology, are a group of three under the name “project_agama.” The team, led by Lauren Connell, an architect at BIG, are touring parts of the Middle East to translate the intricate patterns on ancient tiling into code.

Aided by Baris Yuksel, an engineer at Google and Alexis Burson, an associate at Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, they aim to “make sure that our common heritage is digitized, but not to be saved, instead to find new life in the new buildings.”

To achieve this, the code transcriptions of pattern-work are made accessible through an open source Grasshopper plug-in that makes for “easy panelization of tessellated tile patterns.”

A photo posted by project_agama (@projectagama) on

“This process will both create a record of these works for future generations as well as allow them to be translated into something completely modern and malleable,” the team say on their website. Their approach is arguably much less intrusive than what is being exhibited in Palmyra, however, as a project in progress, its effectiveness remains to be seen.

Speaking specifically about the Palmyra Arch of Triumph replica erected at Trafalgar Square, Stefan Simon hinted at the emergence of a new industrial era. “This ties into a challenge we all are facing—the 4th industrial revolution, the new digital age, providing us with both opportunities and challenges,” he said.

“3D documentation will help us tremendously in conservation, but the discussion on 3D-recreations however, for me, this is interesting more as a process, not so much as a product. This is just a replica, has nothing to do with what shall happen at the site,” Simon commented. “That is a very personal view. I understand it has tremendous potential, for sure, and there are many groups and consortia who are working to document cultural heritage, movable and immovable, in Syria and elsewhere. For example, together with ICOMOS and the California NGO CyArk, we collaborate at Yale IPCH with the Syrian DGAM in the Anqa Project on documenting architectural monuments and sites and providing open access to these data for scholars and global community.”

Further dilemmas though continue to be raised, which Simon addresses. “What do you do with this digitally-born data? How do you preserve that, make sure it doesn’t disappear or the media become obsolete?” Simon asked. “We [conservation professionals], many of us material-focused people, we tend to largely underestimate the challenges linked to the 3D era. I see this virtual world, the 3D recording of sites positively , but we shouldn’t mix that up with the conservation of a site. It isn’t the same.”

“With the attention focusing on Palmyra,” he continued, “let’s not forget there’s tremendous destruction at other World Heritage sites like Aleppo, where the front line passes through the center essentially since 2012, and many other cities. Recently, the commercial quarter of Asrouniyeh in the Old City of Damascus, dating back to the end of of the Ottoman period, was heavily damaged by a rampant fire. With all concerns on Palmyra, we must not forget the Syrian people, who are suffering terribly since years.”

The case for conservation, it seems, will always be a source of debate. Though as architecture critic Jonathan Glancey notes in his book, aptly titled Lost Buildings, “Throughout history humankind has made something of a habit of losing buildings as if these were nothing more substantial than copper coin, a hairpin or set of car keys. Even with our greatest and most celebrated monuments we have been, to say the least, careless.”

Perhaps then, it is best we try our best not to add this growing list of deceased buildings. The Palmyra Arch of Triumph “MkII” will eventually make its way to the city after its globetrotting adventure. However, there it will reside only a stones throw away from its ‘original’ location. Whether it stands as part of a “new” history for Palmyra, or merely fades into its original past, only time will tell.